I was shocked—an editor had just told me that poetry had no place in science books! This young man had been assigned by the publisher to shepherd my completed work-for-hire, about watersheds for middle school readers, into print. The poetry in question was a line or two by contemporary author Gary Snyder, which I had included in the book’s introduction. Although this exchange happened more than a decade ago, it led to the essay below, first drafted in 2009, I would like to share with you today.

I was shocked—an editor had just told me that poetry had no place in science books! This young man had been assigned by the publisher to shepherd my completed work-for-hire, about watersheds for middle school readers, into print. The poetry in question was a line or two by contemporary author Gary Snyder, which I had included in the book’s introduction. Although this exchange happened more than a decade ago, it led to the essay below, first drafted in 2009, I would like to share with you today.

Upcoming Earth Day—with its all its celebrations—has reminded of this essay, as has a brand-new book by local, award-winning poet Joyce Sidman, The Girl Who Drew Butterflies: How Maria Merian’s Art Changed Science (2018). (More on that book, I think, in the next Gone Graphic.) Two of Sidman’s earlier books had figured in the extended written response I ultimately made to that editor’s ignorant remark. I also cited books by two other established, highly-lauded poets; published poems by young authors; and comments about my own sometimes poetic science books for kids. I could have cited many more works. The young man was ignoring a wealth of literature, and underestimating young readers, too!

I was unsure about how to focus my reply, though, until I saw a call for papers for an academic conference centered on “Nature and the Humanities.” I drafted the following essay, which I presented at that Chicago conference in 2009. This presentation dovetailed my work and interest in writing for young readers with my earlier training as a university researcher and teacher. Although the conference program listed me as an “independent scholar,” meaning one without a current university affiliation, even then I preferred being known as a “writer.”

I was unsure about how to focus my reply, though, until I saw a call for papers for an academic conference centered on “Nature and the Humanities.” I drafted the following essay, which I presented at that Chicago conference in 2009. This presentation dovetailed my work and interest in writing for young readers with my earlier training as a university researcher and teacher. Although the conference program listed me as an “independent scholar,” meaning one without a current university affiliation, even then I preferred being known as a “writer.”

Read on to learn more about “Watershed Moments: Poems that Cross Generations and Genres.” And have a wonderful Earth Day, 2018, however you pay tribute to Mother Earth.

—————————

As poet Gary Snyder notes, a “watershed is a marvelous thing to consider: this process of rain falling, streams flowing and oceans evaporating . . . . The watershed is beyond the dichotomy of orderly/disorderly, for its forms are free, but somehow inevitable.” A recent spate of poetry books inspired by Nature supports Snyder’s insights. These books subvert conventional notions of artistic proficiency, distinct genres, and separate audiences.

Young authors now contribute annually to published volumes titled River of Words. This outpouring of talent often begins in classrooms focused on science or environmental issues, or with community groups dedicated to watershed restoration. The Library of Congress cosponsors the yearly writing and art contest which in 1995 began this deluge of creativity. The impact of these poems—whether limpid haiku or cascading torrents of word play—belies the age of their authors. These young people are wise as well as witty.

Young authors now contribute annually to published volumes titled River of Words. This outpouring of talent often begins in classrooms focused on science or environmental issues, or with community groups dedicated to watershed restoration. The Library of Congress cosponsors the yearly writing and art contest which in 1995 began this deluge of creativity. The impact of these poems—whether limpid haiku or cascading torrents of word play—belies the age of their authors. These young people are wise as well as witty.

Other poets writing for young readers recognize this. In volumes such as The Song of the Water Boatman and Other Pond Poems and Butterfly Eyes and Other Secrets of the Meadow, Joyce Sidman conflates genres. The factual explanations she adds after her polished poems do not jar but flow naturally. Lisa Westburg Peters in Earthshake: Poems from the Ground Up and J.Patrick Lewis in Swan Song similarly interpose nonfiction with poetry. The ebb and flow of these illustrated volumes satisfies adult readers as well as children. I will highlight these trends, and then conclude with a few instances of how, when I write “faction” for young readers, I too use poetry to convey scientific concepts.

The River of Words competition offers a teacher’s guide to help educators introduce poetic forms and tropes in relation to environmental issues. There are many styles of poetry displayed in its volumes and on its website. For the sake of brevity and because they reflect my own poetic taste, I will share some of the shorter gems with you today. From the 2008 volume published by Milkweed Press, this is how 9 year-old Damia Lewis describes herself:

I AM

You may think

I am a shadow,

But inside

I am a sun.

A brief, visionary, and luminous statement of hopeful possibilities.

This is how 16 year-old Anna Dumont captures one memorable moment:

GEESE OVER MENDON POND

They came upon us

like I, as a small child,

was always afraid

that a tornado would,

a black mass in the sky,

roaring and cackling,

the occasional high-pitched squeal

like metal on bone.

There were thousands of them,

far more than was necessary,

as if, in the sparse winter,

nature was indulging a little.

Anna Dumont, age 16

A witty and sharp-eyed comment about Nature’s vagaries as well as childhood.

And, finally, in honor of our gathering together today near the shores of Lake Michigan, here is the winner of this year’s Grand Prize in the competition category for grades 7 – 9, now displayed on the River of Words website. Thirteen year-old Patty Schlutt of Grand Rapids, Michigan writes about

Stories Told With Sand Whipping in Our Faces

I was three years old.

My father pulled a map

out of his backpack,

roads spilling across it

like languages I did not understand.

Later, seagulls scampered

through the dunes

as we climbed to a place

where roots laced like fingers over the earth

and Lake Michigan lay before us,

as if it were a guardian.

We stood looking out over the place where

he was born, the hospital

where doctors waited in white shoes

while his throat burned

from tonsillitis. I could see him

a young boy darting through the streets

on his way to the dunes,

the closest thing to heaven

that we have while we live below the stars.

The driveway his father paved

by hand, bruised

from days of bricks

pulling him towards the earth.

His memories fell from his mouth

and I remember them all well

as if it was that morning

and I was standing tall

with his childhood looking back at me.

I believe that these poems speak for themselves, for their creators who are poets first, young poets second. Their vision and artistic proficiency are moving for adult readers as well as their peers.

At the end of this of this paper, I have attached three other poems by young writers, including one written in both English and Spanish. That kind of multiculturalism is typical of this competition, which is an international one, with entries so far from 16 countries. Humanists will also be pleased by the competition’s inclusion of the visual arts, both as a separate award-winning event and in the way it pairs visuals with poems in the anthologies. Another artistic symbiosis occurred in 2002, when multifaceted composer Chris Brubeck, commissioned to create a piece for soprano Frederica von Stade, composed River of Song. Its libretto contains poems by five River of Words young poets as well as e.e. cummings. I have that CD here, and can play a bit at the end of this session or after it if any of you wish.

Joyce Sidman’s award-winning picture books contain poetry that is versatile and sophisticated, giving readers the sensations of Nature before presenting their scientific explanations. In Song of the Water Boatman & Other Pond Poems, these lucid prose explanations appear on the same pages as the poems. In Butterfly Eyes and Other Secrets of the Meadow, each double spread of poems ends with the questions, “What am I?” and the answers are revealed only once the page is turned. A double spread of limpid prose then appears.

Joyce Sidman’s award-winning picture books contain poetry that is versatile and sophisticated, giving readers the sensations of Nature before presenting their scientific explanations. In Song of the Water Boatman & Other Pond Poems, these lucid prose explanations appear on the same pages as the poems. In Butterfly Eyes and Other Secrets of the Meadow, each double spread of poems ends with the questions, “What am I?” and the answers are revealed only once the page is turned. A double spread of limpid prose then appears.

In 2005’s Song of the River Boatman, one device Sidman uses is repetition. Here is the beginning of her poem “Listen to Me”:

Listen to me on a spring night,

on a wet night,

on a rainy night.

Listen for me on a still night

for in the night, I sing.

That is when my heart thaws,

my skin thaws,

my hunger thaws.

That is when the world thaws,

and the air begins to ring.

The prose paragraph that follows the complete poem contains facts about its speaker, the inch-long tree frog called a spring peeper. Sidman later aptly uses a cumulative poem to present the food chain of creatures that feast upon one another in a summer pond. She uses contrapuntal voices to capture the mirrored lives of two water bugs—the water boatman and its upside down twin, the backswimmer. But I believe the synergy between the four quatrains of “The Season’s Campaign” and the prose explanation that floats alongside is a ready demonstration of how Sidman sinks the ideas of distinct genres and of separate—adult vs. child—audiences in her works. She writes

The Season’s Campaign

I.Spring II. Summer

We burst forth, Brown velvet plumes

crisp green squads bob jauntily. On command,

bristling with spears. our slim, waving arrows

We encircle the pond. rush toward the sun.

III. Fall IV. Winter

All red-winged generals Our feet are full of ice.

desert us. Courage Brown bones rattle in the wind.

clumps and fluffs Sleeping, we dream of

like bursting pillows. seed-scouts, sent on ahead.

Sidman then adumbrates what illustrator Becky Prange has depicted in a flowing quadriptych. In a paragraph titled “Cattails,” Sidman explains that

Cattails are plants called emergents, for they grow half in and half out of the water. Their tall, spiky leaves spread around the edges of ponds and shelter many animals. Red-winged blackbirds nest in them, muskrats build mounds with their leaves, and ducks paddle among them, hidden from predators. The most distinctive part of the cattail is its brown “flower,” which looks like sausage on a stick. Soft as a cat’s tail, this flower becomes a fluffy mass of parachuting seeds, spreading with the wind. When tiny cattail seeds fall on moist soil, they sprout and grow new cattails.

Adult as well as younger readers will readily appreciate how cunningly Sidman has woven this information throughout the military parade of her poem.

In the 2006 volume Butterfly Eyes, Sidman continues to address a range of audiences. This is evident in her identifying some of the poetic forms she uses in her titles, such as the poem “We are Waiting (a pantoume).” Turning the page, readers learn that this aptly repetitive poem– beginning and ending with the same line, as pantoums do—describes forest renewal or succession. The added frisson of seeing how subtly the poet has aligned her form with its content need not be present to savor these pieces; yet this knowledge resonates for the informed adult or young reader. And readers mystified by the rather exotic word “pantoume” may be inspired to look up its meaning. Sidman does not talk down to her audience, purportedly elementary school aged readers. Similarly, Sidman’s short poem “He” works on several levels:

In the 2006 volume Butterfly Eyes, Sidman continues to address a range of audiences. This is evident in her identifying some of the poetic forms she uses in her titles, such as the poem “We are Waiting (a pantoume).” Turning the page, readers learn that this aptly repetitive poem– beginning and ending with the same line, as pantoums do—describes forest renewal or succession. The added frisson of seeing how subtly the poet has aligned her form with its content need not be present to savor these pieces; yet this knowledge resonates for the informed adult or young reader. And readers mystified by the rather exotic word “pantoume” may be inspired to look up its meaning. Sidman does not talk down to her audience, purportedly elementary school aged readers. Similarly, Sidman’s short poem “He” works on several levels:

He

trots

through

meadow-gold grass

in dawn sun

furred

mysterious

a word

hunting

its own

meaning

Who is he?

When the next page reveals that this creature is a fox, the adult or sophisticated reader will gain added pleasure from knowing that “foxy” means clever or crafty, but one need not know this to appreciate the other visual and tactile images in this poem.

Lisa Westberg Peters has a very different voice—wry, rollicking, and goodhumored—in her 2003 collection Earthshake: Poems from the Ground Up. She often uses puns and plays with conventional narrative forms to convey her joy in geological facts. Both are apparent in this earthy gem, which takes the form of a set of written directions:

Lisa Westberg Peters has a very different voice—wry, rollicking, and goodhumored—in her 2003 collection Earthshake: Poems from the Ground Up. She often uses puns and plays with conventional narrative forms to convey her joy in geological facts. Both are apparent in this earthy gem, which takes the form of a set of written directions:

Instructions for the Earth’s Dishwasher

Please set the

continental plates

gently on the

continental shelves.

No jostling or scraping.

Please stack the

basins right side up.

No tilting or turning

upside-down.

Please scrape the mud

out of the mud pots.

But watch out!

They’re still hot.

As for the forks

in the river,

just let them soak.

Remember,

if anything breaks,

it’s your fault.

In the End Notes for this book. under this poem’s title, Peters explains that

Some complex geological features have simple, everyday names. For example, a plate is a section of the earth’s outer layer, or crust. A basin is a low area in the earth’s crust. A shelf is an underwater platform on the edge of a continent. Mud pots are formed when rising steam changes rock into clay. A river is “forked” when it has more than one branch. A fault is a crack in the earth’s crust.

Other fun-filled poems in this anthology take the forms of a love letter, an obituary, want ads, a warning label, and recipes. . The title poem, “Earthshake,” is a recipe for a frothy beverage—akin to a milkshake! In each instance, an End Note explains the science behind the poem. I believe Peters’ inspired whimsy appeals to old as well as young and is an effective bridge linking poetry and prose.

J. Patrick Lewis takes a slightly-more more solemn tone in his 2003 collection, Swan Song, which befits its subtitle: Poems of Extinction. As he explains in his melodious and onamtopoeia-rich Foreward,

J. Patrick Lewis takes a slightly-more more solemn tone in his 2003 collection, Swan Song, which befits its subtitle: Poems of Extinction. As he explains in his melodious and onamtopoeia-rich Foreward,

This book is about the recently departed. In Earth’s great forests and fields, they buzzed and chirped and bellowed through little incidents of sorrow from roughly 1627 to 2000. Whether beautiful or homely, giant or dwarf, each species was its own drama in many disappearing acts, even if it was very far off the Broadway of the dinosaurs.

As you can see from the sophisticated language and sentence structure of this paragraph, Lewis’s audience encompasses both old and young readers. The poet uses End Notes to explain the history of each vanished species, eulogized in a poem, such as this one which—bittersweetly—yields both the volume’s title and shorthand for extinction itself:

Chatham Island Swan

Chatham Island, rich and rare resort

For migratory marvels on the wind,

Is something of an empty royal court:

A paradise without a queen and king.

Exotic birds were commoners to those,

Who once, an age ago, could silhouette

In symmetry and S on S, and pose,

Or glorify a shoreline, dripping wet.

But beauty is handmaiden of the strong,

Or else we might have heard

this Swan’s swan song.

Lewis’s graceful play upon “swan song” in the poem’s last line is as elegant as Christopher Wormell’s wood block illustration. And the End Note which explains the extinction of this New Zealand bird is as sophisticated and rich in its prose as the poem itself:

Four hundred fifty miles from any other inhabited land, the group of ten Chatham Islands is a part of New Zealand. Maoris, the first human settlers, populated them in 1000 A.D. The Chatham Island Swan, lovely by being, innocent by nature, defenseless in its habitat, found its way to dinner tables—and to extinction—even before the British colonized the islands in 1791.

Lewis, perhaps even more than Sidman, writes prose that is poetically rhythmic.

Finally, let me just point out a few instances in which I have used poetic language to make science memorable for young readers in picture books. I completed the Amazing Science series, a collection of six books, in 2003 specifically for very young readers—children pre-kindergarten through 3rd grade. Each book had an assigned topic, tailored to grade school curriculum. But I wrapped science concepts in words children could savor and take with them as they grow. For instance, in Dirt: The Scoop on Soil, readers learn that “Squiggling worms, trailing snails, slithering snakes, and burrowing rabbits loosen the soil as they crawl through it.” I am pleased to say that this book is one of 22 that the Minnesota State Department of Agriculture distributes annually to classrooms statewide.

Finally, let me just point out a few instances in which I have used poetic language to make science memorable for young readers in picture books. I completed the Amazing Science series, a collection of six books, in 2003 specifically for very young readers—children pre-kindergarten through 3rd grade. Each book had an assigned topic, tailored to grade school curriculum. But I wrapped science concepts in words children could savor and take with them as they grow. For instance, in Dirt: The Scoop on Soil, readers learn that “Squiggling worms, trailing snails, slithering snakes, and burrowing rabbits loosen the soil as they crawl through it.” I am pleased to say that this book is one of 22 that the Minnesota State Department of Agriculture distributes annually to classrooms statewide.

Light: Shadows, Mirrors, and Rainbows begins with a two page spread that reads:

Delightful Light

Shadows play on a sunny day. Water glints and gleams. At a storm’s end, a rainbow bends.

Wherever you look, light dazzles and dances. It makes wonderful shapes and colors. Light is what lets you see things.

Guidelines for this series called for no more than three sentences per page. I concluded Light with this two page spread:

Guidelines for this series called for no more than three sentences per page. I concluded Light with this two page spread:

All around, light is sparkling, swirling, blinking, bending, and bouncing.

Watch. Wonder. Investigate. Our world is shining with colorful new things to explore.

At times, in this series, guidelines and editorial concerns led me reluctantly towards more plodding prose, but my background in the humanities gave me strength and motivation to resist! And so, in Rocks: Hard, Soft, Smooth, and Rough, readers learn that “Some sedimentary rocks tell stories about the past—stories of forgotten forests and vanished seas. They tell tales of creatures that swam, slithered, or crept.” This book concludes by asking readers to look closely at the rocks around them and asks, “What stories do these rocks tell?”

At times, in this series, guidelines and editorial concerns led me reluctantly towards more plodding prose, but my background in the humanities gave me strength and motivation to resist! And so, in Rocks: Hard, Soft, Smooth, and Rough, readers learn that “Some sedimentary rocks tell stories about the past—stories of forgotten forests and vanished seas. They tell tales of creatures that swam, slithered, or crept.” This book concludes by asking readers to look closely at the rocks around them and asks, “What stories do these rocks tell?”

It pleases me to think that—along with the extraordinary poetry of Sidman, Peters, and Lewis—some of the young authors entering the River of Words competition may have read my science picture books in their school classrooms or libraries.

Copyright 2009 Natalie M. Rosinsky

Works Cited

Brubeck, Chris. “River of Song.” on Convergence (Music CD). NY: Koch Entertainment, 2002.

Lewis, J. Patrick. Swan Song: Poems of Extinction. Mankato, MN: Creative Editions, 2003.

Michael, Barbara, ed. River of Words: Young Poets and Artists on the Nature of Things. Minneapolis: Milkweed, 2008.

Peters, Lisa Westerg. Earthshake: Poems from the Ground Up. NY: HarperCollins, 2003.

Rosinsky, Natalie M. Dirt: The Scoop on Soil. Minneapolis: Picture Window Books, 2003.

————————-. Light: Shadows, Mirrors, and Rainbows. Minneapolis: Picture Window Books, 2003.

————————-. Rocks: Hard, Soft, Shiny, and Smooth. Minneapolis: Picture Window Books, 2003.

Sidman, Joyce. Butterfly Eyes and Other Secrets of the Meadow. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006.

——————. Song of the River Boatman & Other Pond Poems. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005.

Snyder, Gary. A Place in Space: Ethics, Aesthetics, and Watersheds. Berkeley, CA: 1995.

More Poems from River of Words. Minneapolis: Milkweed, 2008:

WHEN I WAS SEARCHING FOR A POEM

a fox stepped out of nowhere.

His long legs stretched across the stone wall.

He paused as we stared,

both wondering where the other was going,

although it was obvious each was wandering—

lost.

I paused as we stared,

both wondering why the other was

using it for direction—

lost.

He wasn’t a sly fox—

At least I didn’t see it in his eyes.

He was frightenend.

I’d never seen a fox before.

I was frightened, too.

There.

A living poem—

A girl, a fox

connected

only by a stone wall

and a fear of the unknown.

Zoe Mason, age 13

PRAYER

Often have I come to you

In the fitful light of evening

Or the constant sheen of morning

And often have I sought your solace,

River.

Show me the secret of your solitude

That thing, that unknown certain thing

Which has brought you through a hundred shifting seasons

And will bring you through at least a thousand more.

Teach me to be alone through summer, autumn, winter, spring

And still to catch the gleaming sunset

And dance in golden eddies in the shadows of the islands.

Tell me all the secrets of those silent seasons

Or one thing only—

When spring comes, show me how to break the ice.

Alexandra Petri, Age 14

THERE IS A DARK RIVER HAY UN RIO OSCURO

There is a dark river En la alcantarilla de la calle

In the gutter of the street En frente de mi escuela

In front of my school. Nacio de la lluvia

It was born in the rain Y no corre mas.

And isn’t flowing any more. Se quieda triste

It’s sort of sad Con goats de gasolina

With drops of gasoline Y un papel rojo

And a red wrapper Que tiro un nino

Some kid tossed Despues de comer un dulce.

After eating a candy. Petro aun triste y sucio

But although it’s sad and filthy Lleva la sombra de mi cara

It carries the shadow of my face Las nubes andrajosas

The tattered clouds Y en blanco y negro

And in white and black Todo el cielo.

The whole sky.

Michelle Diaz Garza, age 9

& Rosa Baum, age 9

A brand new, sumptuous picture book biography is my focus today. Its illustrations refreshed my winter-weary eyes, even as its crystal-clear language movingly revealed an exceptional woman, from girlhood through old age. And, whether by remarkable coincidence or fate, my writing now about Joyce Sidman’s The Girl Who Drew Butterflies: How Maria Merian’s Art Changed Science (2018) seems meant to be. Let me explain.

A brand new, sumptuous picture book biography is my focus today. Its illustrations refreshed my winter-weary eyes, even as its crystal-clear language movingly revealed an exceptional woman, from girlhood through old age. And, whether by remarkable coincidence or fate, my writing now about Joyce Sidman’s The Girl Who Drew Butterflies: How Maria Merian’s Art Changed Science (2018) seems meant to be. Let me explain. The Bassett Table, being produced by a local theater company I saw several performances of this funny play, as scientific Lady Valeria’s disapproving father was acted by my husband, Don Larsson. His shock and disgust when “daughter” Valeria thrusts a six-foot long tape worm at him evoked laughter in the audience but also a few sympathetic groans.

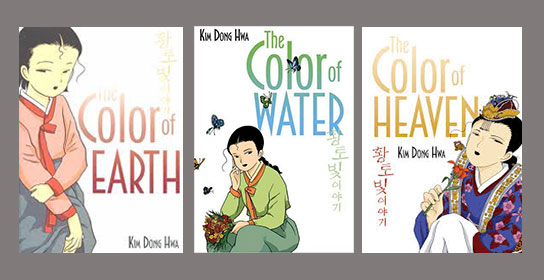

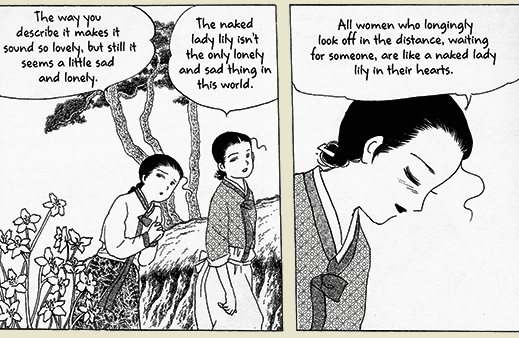

The Bassett Table, being produced by a local theater company I saw several performances of this funny play, as scientific Lady Valeria’s disapproving father was acted by my husband, Don Larsson. His shock and disgust when “daughter” Valeria thrusts a six-foot long tape worm at him evoked laughter in the audience but also a few sympathetic groans.  In this book’s twelve chapters, Sidman explains what life was like in 17th –century Germany for middle class women. Unlike aristocratic Lady Valeria, Maria Merian had to contribute to her household’s income and even support herself late in life. She was the daughter of a printmaker, then step-daughter of one working painter and wife to another painter. While women in such households might perform tasks relating to art, they were not trained formally or accepted as professional artists. Similarly, few people back then believed that women had the brains or temperament to study the natural world. In fact, women who showed interest or special knowledge of nature might be burned as witches! Most insects, even the butterflies which were Maria’s special love, were considered “evil vermin.” Marriage and motherhood were the roles she was expected to fulfill—and she did.

In this book’s twelve chapters, Sidman explains what life was like in 17th –century Germany for middle class women. Unlike aristocratic Lady Valeria, Maria Merian had to contribute to her household’s income and even support herself late in life. She was the daughter of a printmaker, then step-daughter of one working painter and wife to another painter. While women in such households might perform tasks relating to art, they were not trained formally or accepted as professional artists. Similarly, few people back then believed that women had the brains or temperament to study the natural world. In fact, women who showed interest or special knowledge of nature might be burned as witches! Most insects, even the butterflies which were Maria’s special love, were considered “evil vermin.” Marriage and motherhood were the roles she was expected to fulfill—and she did.  But Maria also continued to observe, think about, draw, and paint insects as they developed in their own habitats. She later shared these interests with her daughters, who painted their own still-lifes. Their achievements, though, were of a lesser order than Maria’s. Documenting the origin, metamorphosis, and particular sites of different butterfly species was her signal contribution to science and art history. Seventy-five years before the word “entomologist” came into usage, Maria Merian’s nature studies were praised by science-minded members of the British Royal Society. Her colorful and detailed engravings of creatures depicted in their shared natural setting later influenced the prominent naturalist-artist John Jacques Audubon.

But Maria also continued to observe, think about, draw, and paint insects as they developed in their own habitats. She later shared these interests with her daughters, who painted their own still-lifes. Their achievements, though, were of a lesser order than Maria’s. Documenting the origin, metamorphosis, and particular sites of different butterfly species was her signal contribution to science and art history. Seventy-five years before the word “entomologist” came into usage, Maria Merian’s nature studies were praised by science-minded members of the British Royal Society. Her colorful and detailed engravings of creatures depicted in their shared natural setting later influenced the prominent naturalist-artist John Jacques Audubon.  Sidman supplements the narrative chapters with nine sidebars on such apt topics as copper engraving, witch hunts, religion in the 1600s, and the differences between moths and butterflies. The sidebar on slavery in Surinam, the South American Dutch colony to which Maria daringly journeyed to observe exotic insects and amphibians, is especially important for the young readers in grades 5 and up who might pleasurably explore this book. This sidebar provides needed historical information and context for how unusual for that time Maria’s awareness of slave women’s suffering and lore was. Her views are recorded in her 1705 book.

Sidman supplements the narrative chapters with nine sidebars on such apt topics as copper engraving, witch hunts, religion in the 1600s, and the differences between moths and butterflies. The sidebar on slavery in Surinam, the South American Dutch colony to which Maria daringly journeyed to observe exotic insects and amphibians, is especially important for the young readers in grades 5 and up who might pleasurably explore this book. This sidebar provides needed historical information and context for how unusual for that time Maria’s awareness of slave women’s suffering and lore was. Her views are recorded in her 1705 book. Readers old as well as young will appreciate the brief poems Sidman offers at the beginning of chapters, all titled sequentially by the stages in butterfly development. Each poem is illustrated with a full-color photograph of a stage, while the poem itself cunningly applies not just to the pictured insect but to the chapter’s comparable stage in Maria’s life. So, the caterpillar which has again shed its skin and teen-aged Maria about to be married are both eloquently described by this verse: “I grow quickly, shedding skin after skin, twisting, shifting to match my surroundings.” In the chapter titled “Flight,” an airborne butterfly and Maria’s bold trip to faraway Surinam are both captured in these words: “How vast the swirling dome of the sky! How strong the wings I have grown for myself!”

Readers old as well as young will appreciate the brief poems Sidman offers at the beginning of chapters, all titled sequentially by the stages in butterfly development. Each poem is illustrated with a full-color photograph of a stage, while the poem itself cunningly applies not just to the pictured insect but to the chapter’s comparable stage in Maria’s life. So, the caterpillar which has again shed its skin and teen-aged Maria about to be married are both eloquently described by this verse: “I grow quickly, shedding skin after skin, twisting, shifting to match my surroundings.” In the chapter titled “Flight,” an airborne butterfly and Maria’s bold trip to faraway Surinam are both captured in these words: “How vast the swirling dome of the sky! How strong the wings I have grown for myself!”  Sidman took most of the sharp-eyed photographs here herself. I particularly enjoyed the one of her young neighbor eyeballing a butterfly, shot in a Twin Cities suburb not far from the one where I live! The bulk of the book’s gorgeous illustrations, though, are reproductions of Maria Merian’s own detailed, beautifully-colored images of flowers, plants, insects, and other creatures. They are a delight, extending to the interior covers of this volume, which is a joy to hold. The maps and contemporaneous engravings of city scenes related to Maria’s life, along with back matter such as a timeline and an introductory butterfly glossary, are further reasons to recommend this thoughtfully designed and creatively executed biography.

Sidman took most of the sharp-eyed photographs here herself. I particularly enjoyed the one of her young neighbor eyeballing a butterfly, shot in a Twin Cities suburb not far from the one where I live! The bulk of the book’s gorgeous illustrations, though, are reproductions of Maria Merian’s own detailed, beautifully-colored images of flowers, plants, insects, and other creatures. They are a delight, extending to the interior covers of this volume, which is a joy to hold. The maps and contemporaneous engravings of city scenes related to Maria’s life, along with back matter such as a timeline and an introductory butterfly glossary, are further reasons to recommend this thoughtfully designed and creatively executed biography.  Sidman’s book is more kid-friendly than another recent work about the artist-naturalist, Maria Sibylla Merian: Artist/Scientist/Adventurer (2018), written by Sarah B. Pomeroy and Jeyaraney Kathirithamby. That richly-illustrated book published by the J. Paul Getty Museum on heavy paper stock does, though, contain some information not in The Girl Who Drew Butterflies: sidebars on 17th –century women painters and on Maria’s daughters’ art. It also has a chapter about how Maria’s work and reputation survived and grew, thanks in part to her daughter Dorothea. Those are some reasons for a further look at this art history-oriented book.

Sidman’s book is more kid-friendly than another recent work about the artist-naturalist, Maria Sibylla Merian: Artist/Scientist/Adventurer (2018), written by Sarah B. Pomeroy and Jeyaraney Kathirithamby. That richly-illustrated book published by the J. Paul Getty Museum on heavy paper stock does, though, contain some information not in The Girl Who Drew Butterflies: sidebars on 17th –century women painters and on Maria’s daughters’ art. It also has a chapter about how Maria’s work and reputation survived and grew, thanks in part to her daughter Dorothea. Those are some reasons for a further look at this art history-oriented book. Metamorphosis (2007). I have just begun to peruse this award-winning work aimed at adults, breath-taking in scope and insights into 17th -century women’s lives and the implications of scientific knowledge. I also appreciate how Todd includes her own experiences and thoughts as she travelled to research this biography. Nature and poetry lovers of all ages would find much to enjoy in Joyce Sidman’s other books, listed at her website.

Metamorphosis (2007). I have just begun to peruse this award-winning work aimed at adults, breath-taking in scope and insights into 17th -century women’s lives and the implications of scientific knowledge. I also appreciate how Todd includes her own experiences and thoughts as she travelled to research this biography. Nature and poetry lovers of all ages would find much to enjoy in Joyce Sidman’s other books, listed at her website.  Finally, when it comes to picturing butterflies, I would be remiss in not mentioning for older readers the graphic novel Ruins (2015) by author/illustrator Peter Kuper. (I reviewed one of his earlier books here.) Alternating the story of monarch butterfly migration with the journey of a married couple, this 300 page novel in 2016 won an Eisner Award and was also a Book List Top Ten Graphic Novel.

Finally, when it comes to picturing butterflies, I would be remiss in not mentioning for older readers the graphic novel Ruins (2015) by author/illustrator Peter Kuper. (I reviewed one of his earlier books here.) Alternating the story of monarch butterfly migration with the journey of a married couple, this 300 page novel in 2016 won an Eisner Award and was also a Book List Top Ten Graphic Novel.

I was shocked—an editor had just told me that poetry had no place in science books! This young man had been assigned by the publisher to shepherd my completed work-for-hire, about watersheds for middle school readers, into print. The poetry in question was a line or two by contemporary author Gary Snyder, which I had included in the book’s introduction. Although this exchange happened more than a decade ago, it led to the essay below, first drafted in 2009, I would like to share with you today.

I was shocked—an editor had just told me that poetry had no place in science books! This young man had been assigned by the publisher to shepherd my completed work-for-hire, about watersheds for middle school readers, into print. The poetry in question was a line or two by contemporary author Gary Snyder, which I had included in the book’s introduction. Although this exchange happened more than a decade ago, it led to the essay below, first drafted in 2009, I would like to share with you today. I was unsure about how to focus my reply, though, until I saw a call for papers for

I was unsure about how to focus my reply, though, until I saw a call for papers for  Young authors now contribute annually to published volumes titled River of Words. This outpouring of talent often begins in classrooms focused on science or environmental issues, or with community groups dedicated to watershed restoration. The Library of Congress cosponsors the yearly writing and art contest which in 1995 began this deluge of creativity. The impact of these poems—whether limpid haiku or cascading torrents of word play—belies the age of their authors. These young people are wise as well as witty.

Young authors now contribute annually to published volumes titled River of Words. This outpouring of talent often begins in classrooms focused on science or environmental issues, or with community groups dedicated to watershed restoration. The Library of Congress cosponsors the yearly writing and art contest which in 1995 began this deluge of creativity. The impact of these poems—whether limpid haiku or cascading torrents of word play—belies the age of their authors. These young people are wise as well as witty. Joyce Sidman’s award-winning picture books contain poetry that is versatile and sophisticated, giving readers the sensations of Nature before presenting their scientific explanations. In Song of the Water Boatman & Other Pond Poems, these lucid prose explanations appear on the same pages as the poems. In Butterfly Eyes and Other Secrets of the Meadow, each double spread of poems ends with the questions, “What am I?” and the answers are revealed only once the page is turned. A double spread of limpid prose then appears.

Joyce Sidman’s award-winning picture books contain poetry that is versatile and sophisticated, giving readers the sensations of Nature before presenting their scientific explanations. In Song of the Water Boatman & Other Pond Poems, these lucid prose explanations appear on the same pages as the poems. In Butterfly Eyes and Other Secrets of the Meadow, each double spread of poems ends with the questions, “What am I?” and the answers are revealed only once the page is turned. A double spread of limpid prose then appears.  In the 2006 volume Butterfly Eyes, Sidman continues to address a range of audiences. This is evident in her identifying some of the poetic forms she uses in her titles, such as the poem “We are Waiting (a pantoume).” Turning the page, readers learn that this aptly repetitive poem– beginning and ending with the same line, as pantoums do—describes forest renewal or succession. The added frisson of seeing how subtly the poet has aligned her form with its content need not be present to savor these pieces; yet this knowledge resonates for the informed adult or young reader. And readers mystified by the rather exotic word “pantoume” may be inspired to look up its meaning. Sidman does not talk down to her audience, purportedly elementary school aged readers. Similarly, Sidman’s short poem “He” works on several levels:

In the 2006 volume Butterfly Eyes, Sidman continues to address a range of audiences. This is evident in her identifying some of the poetic forms she uses in her titles, such as the poem “We are Waiting (a pantoume).” Turning the page, readers learn that this aptly repetitive poem– beginning and ending with the same line, as pantoums do—describes forest renewal or succession. The added frisson of seeing how subtly the poet has aligned her form with its content need not be present to savor these pieces; yet this knowledge resonates for the informed adult or young reader. And readers mystified by the rather exotic word “pantoume” may be inspired to look up its meaning. Sidman does not talk down to her audience, purportedly elementary school aged readers. Similarly, Sidman’s short poem “He” works on several levels: Lisa Westberg Peters has a very different voice—wry, rollicking, and goodhumored—in her 2003 collection Earthshake: Poems from the Ground Up. She often uses puns and plays with conventional narrative forms to convey her joy in geological facts. Both are apparent in this earthy gem, which takes the form of a set of written directions:

Lisa Westberg Peters has a very different voice—wry, rollicking, and goodhumored—in her 2003 collection Earthshake: Poems from the Ground Up. She often uses puns and plays with conventional narrative forms to convey her joy in geological facts. Both are apparent in this earthy gem, which takes the form of a set of written directions: J. Patrick Lewis takes a slightly-more more solemn tone in his 2003 collection, Swan Song, which befits its subtitle: Poems of Extinction. As he explains in his melodious and onamtopoeia-rich Foreward,

J. Patrick Lewis takes a slightly-more more solemn tone in his 2003 collection, Swan Song, which befits its subtitle: Poems of Extinction. As he explains in his melodious and onamtopoeia-rich Foreward,  Finally, let me just point out a few instances in which I have used poetic language to make science memorable for young readers in picture books. I completed the Amazing Science series, a collection of six books, in 2003 specifically for very young readers—children pre-kindergarten through 3rd grade. Each book had an assigned topic, tailored to grade school curriculum. But I wrapped science concepts in words children could savor and take with them as they grow. For instance, in Dirt: The Scoop on Soil, readers learn that “Squiggling worms, trailing snails, slithering snakes, and burrowing rabbits loosen the soil as they crawl through it.” I am pleased to say that this book is one of 22 that the Minnesota State Department of Agriculture distributes annually to classrooms statewide.

Finally, let me just point out a few instances in which I have used poetic language to make science memorable for young readers in picture books. I completed the Amazing Science series, a collection of six books, in 2003 specifically for very young readers—children pre-kindergarten through 3rd grade. Each book had an assigned topic, tailored to grade school curriculum. But I wrapped science concepts in words children could savor and take with them as they grow. For instance, in Dirt: The Scoop on Soil, readers learn that “Squiggling worms, trailing snails, slithering snakes, and burrowing rabbits loosen the soil as they crawl through it.” I am pleased to say that this book is one of 22 that the Minnesota State Department of Agriculture distributes annually to classrooms statewide.  Guidelines for this series called for no more than three sentences per page. I concluded Light with this two page spread:

Guidelines for this series called for no more than three sentences per page. I concluded Light with this two page spread: At times, in this series, guidelines and editorial concerns led me reluctantly towards more plodding prose, but my background in the humanities gave me strength and motivation to resist! And so, in Rocks: Hard, Soft, Smooth, and Rough, readers learn that “Some sedimentary rocks tell stories about the past—stories of forgotten forests and vanished seas. They tell tales of creatures that swam, slithered, or crept.” This book concludes by asking readers to look closely at the rocks around them and asks, “What stories do these rocks tell?”

At times, in this series, guidelines and editorial concerns led me reluctantly towards more plodding prose, but my background in the humanities gave me strength and motivation to resist! And so, in Rocks: Hard, Soft, Smooth, and Rough, readers learn that “Some sedimentary rocks tell stories about the past—stories of forgotten forests and vanished seas. They tell tales of creatures that swam, slithered, or crept.” This book concludes by asking readers to look closely at the rocks around them and asks, “What stories do these rocks tell?”  Awkward middle schoolers gaining confidence and becoming brave— two great graphic novels about this transition are my focus today, inspired by current events.

Awkward middle schoolers gaining confidence and becoming brave— two great graphic novels about this transition are my focus today, inspired by current events.  Knowing about the success of past protests may also be inspirational. There were shout-outs to the civil rights movement in several U.S. demonstrations last Saturday. Speakers at the Washington, D.C. march included not only survivors of gun violence but the 9 year-old granddaughter of Dr. Martin Luther King, Yolanda Renee King. Her own

Knowing about the success of past protests may also be inspirational. There were shout-outs to the civil rights movement in several U.S. demonstrations last Saturday. Speakers at the Washington, D.C. march included not only survivors of gun violence but the 9 year-old granddaughter of Dr. Martin Luther King, Yolanda Renee King. Her own  Yet such historical examples of bravery, perhaps introduced in school, are just one way kids learn to be brave. More immediate and sometimes painful lessons happen through everyday life, which for most Western tweens and teens centers on school. With this in mind, today I want to spotlight two graphic novels that I read recently, after eagerly looking at the American Library Association’s

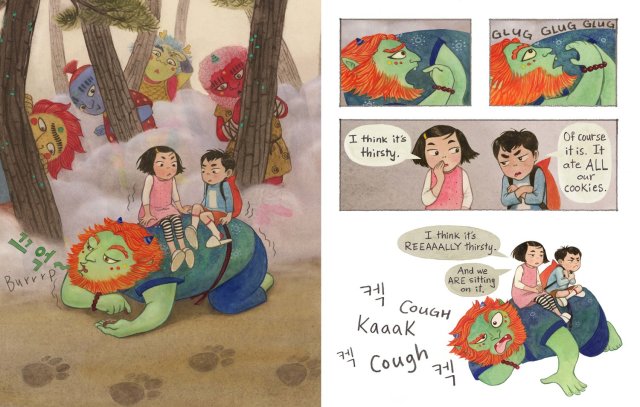

Yet such historical examples of bravery, perhaps introduced in school, are just one way kids learn to be brave. More immediate and sometimes painful lessons happen through everyday life, which for most Western tweens and teens centers on school. With this in mind, today I want to spotlight two graphic novels that I read recently, after eagerly looking at the American Library Association’s  how much she enjoys science, even though the Art Club kids are “at war” with the Science Club! Peppi’s personal growth is accented by the one time that Awkward’s muted palette of mauve and soft browns or blues effectively flares into vivid colors. During a class trip to a science museum, as Peppi imagines herself visiting terrains around the globe, she “sees” them in bright greens, yellows, and shimmering white. This color transformation parallels the strength of the friendship Peppi ultimately develops with equally shy Jaime, a science “nerd,” and the strong way she finally is able to literally shout down some bullies.

how much she enjoys science, even though the Art Club kids are “at war” with the Science Club! Peppi’s personal growth is accented by the one time that Awkward’s muted palette of mauve and soft browns or blues effectively flares into vivid colors. During a class trip to a science museum, as Peppi imagines herself visiting terrains around the globe, she “sees” them in bright greens, yellows, and shimmering white. This color transformation parallels the strength of the friendship Peppi ultimately develops with equally shy Jaime, a science “nerd,” and the strong way she finally is able to literally shout down some bullies. poor, of families which cope with disability and others which break apart due to self-centered anger. We see teachers with lovable foibles and others with fearsome flair. There are several subplots resolved in Awkward, even as we follow the main story about Peppi through the novel’s six chapters and 200 pages. We see Peppi’s life over the course of several months, noting how her emotions trump ordinary clock time. An anxious, sleepless night which feels endless occupies several pages, while the few minutes she spends nervously convincing the art and science clubs to work together to build an indoor planetarium feel like “SEVERAL CENTURIES LATER.” The planetarium is a success, returning both groups to officially approved school status. Peppi learns to be brave by working with others in such efforts as well as speaking out by herself. Or, as Peppi herself concludes, “BUILD THINGS. BUILD FRIENDSHIPS. BUILD YOURSELF.”

poor, of families which cope with disability and others which break apart due to self-centered anger. We see teachers with lovable foibles and others with fearsome flair. There are several subplots resolved in Awkward, even as we follow the main story about Peppi through the novel’s six chapters and 200 pages. We see Peppi’s life over the course of several months, noting how her emotions trump ordinary clock time. An anxious, sleepless night which feels endless occupies several pages, while the few minutes she spends nervously convincing the art and science clubs to work together to build an indoor planetarium feel like “SEVERAL CENTURIES LATER.” The planetarium is a success, returning both groups to officially approved school status. Peppi learns to be brave by working with others in such efforts as well as speaking out by herself. Or, as Peppi herself concludes, “BUILD THINGS. BUILD FRIENDSHIPS. BUILD YOURSELF.”  emphasis as well as to indicate actual changes in spoken volume. Readers of both works will also note their similar, manga-inspired visual style, since both feature faces and some actions drawn unrealistically. Chmakova’s earlier success as creator of manga for publishers Tokyopop and Yen Press is evident in her depiction of impossibly wide frowns and smiles, surprised eyes with pinpoint or no pupils, and doubling of arms and legs to indicate motion. These techniques will delight lovers of manga and be accessible to other readers as this style so cleverly supports each work’s rich storyline and characterization.

emphasis as well as to indicate actual changes in spoken volume. Readers of both works will also note their similar, manga-inspired visual style, since both feature faces and some actions drawn unrealistically. Chmakova’s earlier success as creator of manga for publishers Tokyopop and Yen Press is evident in her depiction of impossibly wide frowns and smiles, surprised eyes with pinpoint or no pupils, and doubling of arms and legs to indicate motion. These techniques will delight lovers of manga and be accessible to other readers as this style so cleverly supports each work’s rich storyline and characterization.  overweight boy, fixated on potential disasters caused by sunspots, was a minor character in Awkward, a member of the middle school Art Club. In Brave, we see how Jensen is physically bullied and teased about his weight, obsessions, and trouble with math, even as some students he considers friends ignore him or make slyly mean jokes at his expense. Jensen’s visualizing his school day as a video game, with a series of leveled obstacles to overcome, is both sad and funny! Pages or panels depicting this game and Jensen’s comforting daydreams are the points at which Awkward’s subdued palette adds some brighter colors.

overweight boy, fixated on potential disasters caused by sunspots, was a minor character in Awkward, a member of the middle school Art Club. In Brave, we see how Jensen is physically bullied and teased about his weight, obsessions, and trouble with math, even as some students he considers friends ignore him or make slyly mean jokes at his expense. Jensen’s visualizing his school day as a video game, with a series of leveled obstacles to overcome, is both sad and funny! Pages or panels depicting this game and Jensen’s comforting daydreams are the points at which Awkward’s subdued palette adds some brighter colors. himself are major points in the novel. Its nuanced characterizations also have his thoughtless friends learning to recognize and change their verbal bullying, while one of the two physical bullies also begins to change. These subplots enrich the 10 chapter novel, which also sees outer-space obsessed Jensen coming to appreciate school athletes, two of whom befriend and stand up for him. As Jensen says to himself, “I guess sports are . . . kinda like their Star Trek.” Such natural sounding thoughts and dialogue are one of the ways Chmakova brings her many characters to life.

himself are major points in the novel. Its nuanced characterizations also have his thoughtless friends learning to recognize and change their verbal bullying, while one of the two physical bullies also begins to change. These subplots enrich the 10 chapter novel, which also sees outer-space obsessed Jensen coming to appreciate school athletes, two of whom befriend and stand up for him. As Jensen says to himself, “I guess sports are . . . kinda like their Star Trek.” Such natural sounding thoughts and dialogue are one of the ways Chmakova brings her many characters to life.  Svetlana Chmakova’s perceptive insights and engaging characters make us eager to read the illustrated autobiographical pieces at the end of each book. She provides relevant details about her life in Russia and as a 15 year-old immigrant to Canada, as well as—in Brave—reassuring scientific facts about sunspots! I believe readers will be happy to learn that a third volume about Berrybrook Middle School’s students, titled Crush,

Svetlana Chmakova’s perceptive insights and engaging characters make us eager to read the illustrated autobiographical pieces at the end of each book. She provides relevant details about her life in Russia and as a 15 year-old immigrant to Canada, as well as—in Brave—reassuring scientific facts about sunspots! I believe readers will be happy to learn that a third volume about Berrybrook Middle School’s students, titled Crush,  first volume of Night School from the local library.) Kids wanting to know more about 1960s civil rights battles would find The Silence of Our Friends, a graphic novel reviewed by me

first volume of Night School from the local library.) Kids wanting to know more about 1960s civil rights battles would find The Silence of Our Friends, a graphic novel reviewed by me  Babymouse is growing up! I recently learned that the perky heroine of

Babymouse is growing up! I recently learned that the perky heroine of  Lights, Camera, Middle School! (2017) is the first in a new series about the wise-cracking, imaginative rodent, who daydreams in pink. Her earlier (mis)adventures have ranged from supposedly being Queen of the World (Babymouse # 1, 2005) to being an Olympic champion who Goes for the Gold (Babymouse # 20, 2016). Along the way, these best-selling humorous books have won numerous awards, including a prestigious Eisner Award in 2013 for best graphic publication for early readers.

Lights, Camera, Middle School! (2017) is the first in a new series about the wise-cracking, imaginative rodent, who daydreams in pink. Her earlier (mis)adventures have ranged from supposedly being Queen of the World (Babymouse # 1, 2005) to being an Olympic champion who Goes for the Gold (Babymouse # 20, 2016). Along the way, these best-selling humorous books have won numerous awards, including a prestigious Eisner Award in 2013 for best graphic publication for early readers.  In the new series, labelled “Babymouse Tales from the Locker,” Lights, Camera, Middle School! describes how Babymouse’s joining Film Club is part of her adjustment to that new environment. Her difficulties, while humorous, are very real. As she says early on, “The hardest subject in middle school . . . was friendship.” The second book in this series, Miss Communication, dealing with social media in middle school, will be published in July, 2018. To distinguish these books, written for older readers, from the first series, the sister-brother team of author Jennifer L. Holm and illustrator Matthew Holm has explained that “We switched up our procedure a bit . . . [from] a traditional graphic novel.” Matt Holm describes the new look as “more like an illustrated chapter book.” Since this book includes graphic novel sequences, however, I would call this work a hybrid novel. I first discussed that graphic trend

In the new series, labelled “Babymouse Tales from the Locker,” Lights, Camera, Middle School! describes how Babymouse’s joining Film Club is part of her adjustment to that new environment. Her difficulties, while humorous, are very real. As she says early on, “The hardest subject in middle school . . . was friendship.” The second book in this series, Miss Communication, dealing with social media in middle school, will be published in July, 2018. To distinguish these books, written for older readers, from the first series, the sister-brother team of author Jennifer L. Holm and illustrator Matthew Holm has explained that “We switched up our procedure a bit . . . [from] a traditional graphic novel.” Matt Holm describes the new look as “more like an illustrated chapter book.” Since this book includes graphic novel sequences, however, I would call this work a hybrid novel. I first discussed that graphic trend  novels for tweens. (I mention some of these Newberry Honor books in a review article

novels for tweens. (I mention some of these Newberry Honor books in a review article  larger one communicate her race to escape, while the use of dark background and a shift in perspective show her terror as a horde of angry lockers pursue and surround her! Then the school bell rings, and our heroine is back to safe reality. At other points, single illustrations complement the author’s words tellingly. For instance, a zombie-like teacher filling a blackboard with homework assignments humorously explains the words “And everywhere you turned, someone was trying to eat your brains.” Despite Babymouse’s misgivings and some actual failures, her middle school really is a safe environment in which to learn and grow. The Holm siblings do a great job of communicating this positive message in a way that engages readers of all ages, not just their targeted audience of 8 to 12 year-olds.

larger one communicate her race to escape, while the use of dark background and a shift in perspective show her terror as a horde of angry lockers pursue and surround her! Then the school bell rings, and our heroine is back to safe reality. At other points, single illustrations complement the author’s words tellingly. For instance, a zombie-like teacher filling a blackboard with homework assignments humorously explains the words “And everywhere you turned, someone was trying to eat your brains.” Despite Babymouse’s misgivings and some actual failures, her middle school really is a safe environment in which to learn and grow. The Holm siblings do a great job of communicating this positive message in a way that engages readers of all ages, not just their targeted audience of 8 to 12 year-olds. And yet—while I definitely recommend the new Babymouse series, looking forward to its next volume—its wholesome portrayal of middle school contrasts so vividly with school images recently in the news. I cannot get those out of my mind. Schools today are not the safe environments portrayed by the Holms . . . but not because of any of the situations Babymouse fears. This past Valentine’s Day saw the single-shooter slaughter of unarmed high school students and staff. Parkland, Florida has now been added to the

And yet—while I definitely recommend the new Babymouse series, looking forward to its next volume—its wholesome portrayal of middle school contrasts so vividly with school images recently in the news. I cannot get those out of my mind. Schools today are not the safe environments portrayed by the Holms . . . but not because of any of the situations Babymouse fears. This past Valentine’s Day saw the single-shooter slaughter of unarmed high school students and staff. Parkland, Florida has now been added to the  middle and even elementary schools. Without school guards, metal detectors, or police officers, Babymouse’s school settings resemble those of more innocent eras, not today’s wary fortresses. The

middle and even elementary schools. Without school guards, metal detectors, or police officers, Babymouse’s school settings resemble those of more innocent eras, not today’s wary fortresses. The  Such thoughts led me to see if any graphic novels or comics have dealt with school shootings. As a result, I am now waiting for mail delivery of the hybrid novel Jamie’s Got a Gun (2014). Written by Canadian educator Gail Sidonie Sobat and illustrated by Spyder Yardley-Jones, it is told from the point-of-view of a teen as he plans a shooting. Will that tragedy be averted? I will need to read the book to find out and evaluate it overall. I decided to pass on the DC Comics series Hard Time (2004 – 2005), as its treatment of a school shooting is framed for adult readers, ones especially interested in odd superpowers.

Such thoughts led me to see if any graphic novels or comics have dealt with school shootings. As a result, I am now waiting for mail delivery of the hybrid novel Jamie’s Got a Gun (2014). Written by Canadian educator Gail Sidonie Sobat and illustrated by Spyder Yardley-Jones, it is told from the point-of-view of a teen as he plans a shooting. Will that tragedy be averted? I will need to read the book to find out and evaluate it overall. I decided to pass on the DC Comics series Hard Time (2004 – 2005), as its treatment of a school shooting is framed for adult readers, ones especially interested in odd superpowers.  My literature search turned up many more all-prose novels focused on school shootings. Some are already downloaded or now on my library request list. Violent Ends: A Novel in Seventeen Points of View (2016), edited by Shaun David Hutchinson, sounds particularly interesting. Its seventeen chapters, written by seventeen different authors including Hutchinson himself, deliberately exclude the viewpoint of its teen-age shooter. Instead, the book portrays the views of the six people he killed

My literature search turned up many more all-prose novels focused on school shootings. Some are already downloaded or now on my library request list. Violent Ends: A Novel in Seventeen Points of View (2016), edited by Shaun David Hutchinson, sounds particularly interesting. Its seventeen chapters, written by seventeen different authors including Hutchinson himself, deliberately exclude the viewpoint of its teen-age shooter. Instead, the book portrays the views of the six people he killed  and the five he injured. Matthew Quick’s Forgive Me, Leonard Peacock (2014), told in a single day as a teen prepares to shoot someone else and himself, is also now on my reading list. It includes the would-be shooter’s meetings with four individuals who have shown him kindness, including a home-schooled girl and a teacher who himself survived the Holocaust. After finishing all these emotionally-intense books, I suspect I will be happy to return to the humor-filled, sharp-eyed but warm-hearted school corridors of the Babymouse books!

and the five he injured. Matthew Quick’s Forgive Me, Leonard Peacock (2014), told in a single day as a teen prepares to shoot someone else and himself, is also now on my reading list. It includes the would-be shooter’s meetings with four individuals who have shown him kindness, including a home-schooled girl and a teacher who himself survived the Holocaust. After finishing all these emotionally-intense books, I suspect I will be happy to return to the humor-filled, sharp-eyed but warm-hearted school corridors of the Babymouse books!  What happens when peacetime resembles war? I will be pondering this question in coming weeks as we celebrate

What happens when peacetime resembles war? I will be pondering this question in coming weeks as we celebrate  2014 omnibus review of graphic literature about World War I) call dramatic attention to how U.S. discrimination against Blacks followed them onto the battlefields of France. This work follows members of the all-Black 369th Battalion—real-life members and some fictionalized amalgams—before, during, and after the Army service for which they had volunteered. A short video

2014 omnibus review of graphic literature about World War I) call dramatic attention to how U.S. discrimination against Blacks followed them onto the battlefields of France. This work follows members of the all-Black 369th Battalion—real-life members and some fictionalized amalgams—before, during, and after the Army service for which they had volunteered. A short video  acknowledged Johnson’s bravery with its Croix de Guerre, its highest military honor, back in 1919. I was also interested to learn that Hollywood star Will Smith is again planning to produce a dramatized version of the Hellfighters’ saga, this time working with TV’s History Channel. In 2014 Smith had previously optioned Brooks’ book for a movie version, a failed plan.

acknowledged Johnson’s bravery with its Croix de Guerre, its highest military honor, back in 1919. I was also interested to learn that Hollywood star Will Smith is again planning to produce a dramatized version of the Hellfighters’ saga, this time working with TV’s History Channel. In 2014 Smith had previously optioned Brooks’ book for a movie version, a failed plan.  watch the news on TV or Facebook to see how wartime violence—with armed, uniformed officers often pitted against unarmed civilians—has become commonplace in today’s so-called peacetime. Too often, these incidents feature White officials firing upon Black citizens, a reflection of U.S. society’s ongoing racism. Today I spotlight an amazing new graphic novel that powerfully epitomizes and gives context to this epidemic of violence: I Am Alfonso Jones (2017), written by Tony Medina and illustrated by Stacey Robinson and John Jennings. Their book also shows how and why the Black Lives Matter movement is a response to this epidemic.

watch the news on TV or Facebook to see how wartime violence—with armed, uniformed officers often pitted against unarmed civilians—has become commonplace in today’s so-called peacetime. Too often, these incidents feature White officials firing upon Black citizens, a reflection of U.S. society’s ongoing racism. Today I spotlight an amazing new graphic novel that powerfully epitomizes and gives context to this epidemic of violence: I Am Alfonso Jones (2017), written by Tony Medina and illustrated by Stacey Robinson and John Jennings. Their book also shows how and why the Black Lives Matter movement is a response to this epidemic. partners Robinson and Jennings show how such a mistake was visually impossible, while Medina’s insightful commentary explains how the officer’s stunted, racist outlook provoked him to a fatal, kneejerk reaction. Believing all Black teens are dangerous, that Blacks are inferior “savages,” and hearing from another customer that there is a Black man with a gun, Officer Whitson in a fearful instant slays Alfonso. This senseless tragedy could have been avoided. As the boy’s grieving mother eloquently says, if Whitson’s schooling and “broader reality. . . movies, TV, whatever. . .” had been different. . . “maybe he would have seen my son as a teenager, as a person, as a citizen, as an American, as a human. . . .”

partners Robinson and Jennings show how such a mistake was visually impossible, while Medina’s insightful commentary explains how the officer’s stunted, racist outlook provoked him to a fatal, kneejerk reaction. Believing all Black teens are dangerous, that Blacks are inferior “savages,” and hearing from another customer that there is a Black man with a gun, Officer Whitson in a fearful instant slays Alfonso. This senseless tragedy could have been avoided. As the boy’s grieving mother eloquently says, if Whitson’s schooling and “broader reality. . . movies, TV, whatever. . .” had been different. . . “maybe he would have seen my son as a teenager, as a person, as a citizen, as an American, as a human. . . .”  on coats for her, his life’s hopes end in a volley of bullets! But that is not where the novel ends. For another 130 pages, we follow the Harlem teen’s journey as a ghost—on an intangible subway train joining the spirits of other, real-life Black victims of senseless violence. Mrs. Eleanor Bumpurs, Amadou Diallo, Michael Stewart, Anthony Baez, and Henry Dumas were each slain in different recent decades in New York City history. Now, as fictional characters, they join Alfonso to journey back and forward in time and place, visiting past injustices and following along as Alfonso’s friends, family, and community grieve and protest his death.

on coats for her, his life’s hopes end in a volley of bullets! But that is not where the novel ends. For another 130 pages, we follow the Harlem teen’s journey as a ghost—on an intangible subway train joining the spirits of other, real-life Black victims of senseless violence. Mrs. Eleanor Bumpurs, Amadou Diallo, Michael Stewart, Anthony Baez, and Henry Dumas were each slain in different recent decades in New York City history. Now, as fictional characters, they join Alfonso to journey back and forward in time and place, visiting past injustices and following along as Alfonso’s friends, family, and community grieve and protest his death.  Entirely wordless pages also advance the story here. As the book opens, before we really know who Alfonso is, we silently witness the first bullet to strike the teen. We are “hooked” by this two page sequence, paced so deftly by Robinson and Jennings with techniques they then use throughout the book. They move deftly between long distance and close-up views, breaking panel frames to great effect and sometimes eliminating panels altogether to create a sense of motion or time. I Am Alfonso Jones deserves the many accolades it has already garnered from writers, graphic artists, and reviewers. It is, I feel, a sure contender for awards in the coming year. A teachers’ guide to the novel is also available at its publisher’s

Entirely wordless pages also advance the story here. As the book opens, before we really know who Alfonso is, we silently witness the first bullet to strike the teen. We are “hooked” by this two page sequence, paced so deftly by Robinson and Jennings with techniques they then use throughout the book. They move deftly between long distance and close-up views, breaking panel frames to great effect and sometimes eliminating panels altogether to create a sense of motion or time. I Am Alfonso Jones deserves the many accolades it has already garnered from writers, graphic artists, and reviewers. It is, I feel, a sure contender for awards in the coming year. A teachers’ guide to the novel is also available at its publisher’s  What else will I be reading or rereading this coming Black History month? Once I stop feeling devastated by I Am Alfonso Jones, I might

What else will I be reading or rereading this coming Black History month? Once I stop feeling devastated by I Am Alfonso Jones, I might  catch up with the all-prose looks at unwarranted White police violence in All-American Boys (2015) by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely or The Hate U Give (2017) by Angie Thomas. (A

catch up with the all-prose looks at unwarranted White police violence in All-American Boys (2015) by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely or The Hate U Give (2017) by Angie Thomas. (A  First, though, the stand-out visual storytelling in Alfonso will have me catching up with the graphic novel adaptation of one of my favorite contemporary classics, Octavia Butler’s Kindred (1979; 1988; 2004). That haunting, award-winning novel about time travel to the slave-holding American South, illustrated by Alfonso’s John Jennings and adapted by Damian Duffy, just last year became an acclaimed best-seller as Kindred: A Graphic Novel Adaptation (2017). Both versions depict the cruel, warlike violence typical in the supposedly peaceful South.

First, though, the stand-out visual storytelling in Alfonso will have me catching up with the graphic novel adaptation of one of my favorite contemporary classics, Octavia Butler’s Kindred (1979; 1988; 2004). That haunting, award-winning novel about time travel to the slave-holding American South, illustrated by Alfonso’s John Jennings and adapted by Damian Duffy, just last year became an acclaimed best-seller as Kindred: A Graphic Novel Adaptation (2017). Both versions depict the cruel, warlike violence typical in the supposedly peaceful South.  Ring out the old, ring in the new,

Ring out the old, ring in the new, Award-winning author Kij Johnson has written a wonderful sequel to Kenneth Grahame’s classic animal fable, The Wind in the Willows (1908), creating female characters Beryl Mole and Lottie Rabbit, who join his male protagonists–brave Water Rat, loyal Mole, wise Badger, and reckless Toad—in new adventures. In The River Bank, Beryl and Lottie establish their own peaceful home and routines along that shore, and later also triumph over motor cycle accidents and kidnapping by criminal weasels! Illustrator Kathleen Jennings provides delicate, character-rich line drawings in full-page and many spot illustrations that highlight the story, reinforcing and enriching its early 20th century setting.

Award-winning author Kij Johnson has written a wonderful sequel to Kenneth Grahame’s classic animal fable, The Wind in the Willows (1908), creating female characters Beryl Mole and Lottie Rabbit, who join his male protagonists–brave Water Rat, loyal Mole, wise Badger, and reckless Toad—in new adventures. In The River Bank, Beryl and Lottie establish their own peaceful home and routines along that shore, and later also triumph over motor cycle accidents and kidnapping by criminal weasels! Illustrator Kathleen Jennings provides delicate, character-rich line drawings in full-page and many spot illustrations that highlight the story, reinforcing and enriching its early 20th century setting.

might have done had they existed in some of the literary classics she loved. The Far Bank and similar rewritten classics, she adds, “build a story that opens up the ignored, forgotten, or blocked-off passageways in the original. It’s a mark of our affection for a work that we labor so hard to understand and, perhaps, to redeem it.” Johnson’s pitch-perfect recreation of Kenneth Grahame’s poetic, high-flown language is one of the marvels of this sequel, which may be enjoyed on its own, without ever having read The Wind in the Willows. But readers will experience more joy and meaning from such luminous phrases as “an animal lives in the long now of the world” if they have already read Grahame’s work. I suspect that young readers who pick up Johnson’s book first will make their way soon to the original.

might have done had they existed in some of the literary classics she loved. The Far Bank and similar rewritten classics, she adds, “build a story that opens up the ignored, forgotten, or blocked-off passageways in the original. It’s a mark of our affection for a work that we labor so hard to understand and, perhaps, to redeem it.” Johnson’s pitch-perfect recreation of Kenneth Grahame’s poetic, high-flown language is one of the marvels of this sequel, which may be enjoyed on its own, without ever having read The Wind in the Willows. But readers will experience more joy and meaning from such luminous phrases as “an animal lives in the long now of the world” if they have already read Grahame’s work. I suspect that young readers who pick up Johnson’s book first will make their way soon to the original. So, in a new year valuing continuity as well as change, I will point out the welcome, continued publication of comic book series with racially and culturally diverse heroines and heroes. Kamala Khan, the Pakistani-American, Muslim Ms. Marvel, reviewed

So, in a new year valuing continuity as well as change, I will point out the welcome, continued publication of comic book series with racially and culturally diverse heroines and heroes. Kamala Khan, the Pakistani-American, Muslim Ms. Marvel, reviewed  (2017). Volume 4 will be published in a few weeks and Volume 5 is set for July, 2018 publication. Other characters in that Marvel comic book universe have called nine-year old, science-loving Lunella “one of the smartest people” in their world! While its sales figures are not super high, a troubling trend, devoted fans of this comic book series are discussing ways it would make a great animated film or TV show. Miles Morales, the Afro-Latino American Spiderman, also continues to be published, appearing in his own series and as a side character in other related titles.