Heartthrob or heartache? Sudden attraction or slow connection? With Valentine’s Day approaching, and its card exchanges popular even in some pre-schools, the recent publication of Svetlana Chmakova’s Crush (2018) was aptly timed. This continuation of the author/illustrator’s award-winning Berrybrook Middle School series targets tween readers, the age at which crushes typically first loom large. Today I look at this very enjoyable, satisfying graphic novel and another recent graphic work about first and ongoing loves, M. Dean’s memorable I Am Young (2018). That book will appeal more to teen and older readers, with its look back at how folks frequently used to get and manage crushes, before these days of (often successful) online dating websites.

Heartthrob or heartache? Sudden attraction or slow connection? With Valentine’s Day approaching, and its card exchanges popular even in some pre-schools, the recent publication of Svetlana Chmakova’s Crush (2018) was aptly timed. This continuation of the author/illustrator’s award-winning Berrybrook Middle School series targets tween readers, the age at which crushes typically first loom large. Today I look at this very enjoyable, satisfying graphic novel and another recent graphic work about first and ongoing loves, M. Dean’s memorable I Am Young (2018). That book will appeal more to teen and older readers, with its look back at how folks frequently used to get and manage crushes, before these days of (often successful) online dating websites.

Crush’s central character, 13 year-old Jorge Ruiz, first appeared in Chmalkova’s Brave (2015) and Awkward (2017), reviewed by me here,but Crush works well as a stand-alone-novel, too. I believe that readers who first experience engaging Jorge’s point-of-view here will eagerly seek out those other Berrybrook Middle School works! Chmakova does a great job communicating how Jorge’s big, athletic build—his stereotypical “jock” appearance—does not match his sensitive nature and thoughtful mind. He is one of Berrybrook’s unofficial peacekeepers, watching out for other kids at risk from bullying, and quietly annoyed at how crushes are the hot topic at school.

Crush’s central character, 13 year-old Jorge Ruiz, first appeared in Chmalkova’s Brave (2015) and Awkward (2017), reviewed by me here,but Crush works well as a stand-alone-novel, too. I believe that readers who first experience engaging Jorge’s point-of-view here will eagerly seek out those other Berrybrook Middle School works! Chmakova does a great job communicating how Jorge’s big, athletic build—his stereotypical “jock” appearance—does not match his sensitive nature and thoughtful mind. He is one of Berrybrook’s unofficial peacekeepers, watching out for other kids at risk from bullying, and quietly annoyed at how crushes are the hot topic at school.

Wordless panels and others with word balloons filled only with ellipses show us Jorge’s gradual, then stunned realization that he too now has a crush—on classmate Jazmine Duong. As the novel’s eleven chapters unfold, we see Jorge later daydreaming about Jazmine in even softer pastels and also read his astute, rueful conclusion about his own change-of-heart about crushes: “I guess that’s why you can predict movie plots . . . but can’t predict life.”

Wordless panels and others with word balloons filled only with ellipses show us Jorge’s gradual, then stunned realization that he too now has a crush—on classmate Jazmine Duong. As the novel’s eleven chapters unfold, we see Jorge later daydreaming about Jazmine in even softer pastels and also read his astute, rueful conclusion about his own change-of-heart about crushes: “I guess that’s why you can predict movie plots . . . but can’t predict life.”

Chmakova’s visual style, employing the manga conventions of cheek lines for blushes and wide mouths for other strong emotions, supports Crush’s story lines and character development. Sub plots involving some self-centered and insecure tween characters add dimension to school life here, as does the understated  depiction of a hajib-wearing gym coach, a lesbian teacher whose wife accompanies her to school events, and what appears to be a non-binary drama club character, Nic. This rich texture of daily and seasonal school events adds heft and poignancy to the slow development of Jorge and Jazmine’s relationship from friends to “boyfriend” and “girlfriend.”

depiction of a hajib-wearing gym coach, a lesbian teacher whose wife accompanies her to school events, and what appears to be a non-binary drama club character, Nic. This rich texture of daily and seasonal school events adds heft and poignancy to the slow development of Jorge and Jazmine’s relationship from friends to “boyfriend” and “girlfriend.”

Even figuring out how to ask for—or give—a phone number for texting is a situation the pair realistically stumbles through. Along the way, Chmakova points out that Jorge admires Jazmine’s spirit and not just her appearance, unlike another shallow character. We see that sincere dating duos, like real friends, steadfastly support one another’s efforts and events. A cheek kiss and a “Hi, Jorge” sweetly conclude this tween-age saga. Chmakova’s fans will further appreciate the author’s “Afterward,” interestingly and entertainingly showing how over months she developed Crush, becoming a mom during this time period, too.

That conjunction between adult life, often linked to parenthood, and its frequently problematic relationship to tween or teen crushes is central to M. Dean’s I Am Young. This visually lush book contains six short stories spotlighting such intense emotional connections, also including a non-romantic one between two female best friends. A widowed father and adult daughter who no longer “connect” figure poignantly in another story. All these distinct stories, some set in the U.S. and others in Great Britain, alternate with episodes in a seventh, prominent framing story—the saga of one couple’s relationship with one another, begun as a sudden crush, when Miriam and George meet as teenagers at a Beatles concert in 1964 Britain. We follow that crush, continued at first through hand-written letters, throughout the pair’s lives, the passage of time signaled by different Beatles album covers as well as Miriam and George’s whitened hair. Regardless of age, Dean’s characters all have the large eyes and simple facial features and bodies of cartoon characters.

That conjunction between adult life, often linked to parenthood, and its frequently problematic relationship to tween or teen crushes is central to M. Dean’s I Am Young. This visually lush book contains six short stories spotlighting such intense emotional connections, also including a non-romantic one between two female best friends. A widowed father and adult daughter who no longer “connect” figure poignantly in another story. All these distinct stories, some set in the U.S. and others in Great Britain, alternate with episodes in a seventh, prominent framing story—the saga of one couple’s relationship with one another, begun as a sudden crush, when Miriam and George meet as teenagers at a Beatles concert in 1964 Britain. We follow that crush, continued at first through hand-written letters, throughout the pair’s lives, the passage of time signaled by different Beatles album covers as well as Miriam and George’s whitened hair. Regardless of age, Dean’s characters all have the large eyes and simple facial features and bodies of cartoon characters.

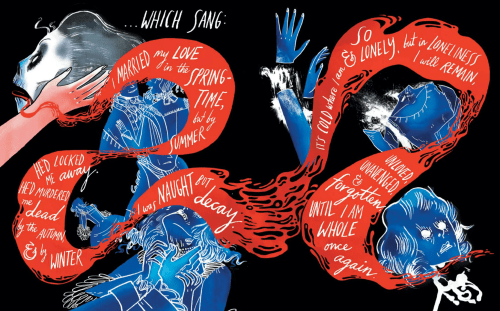

Music is important throughout I Am Young, with Dean altering her color palette and graphic style to match her other characters’ very distinct musical tastes and eras, along with the each story’s plot line. Miriam and George’s Beatlemania is shown in black-and-white, while Lisa’s later psychedelic tripping to the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds is depicted in deep pink, gold, and green swirls. High school seniors and best friends Kennedy and Rhea, whose growing differences are summed up in their opposing views of pop singer Tom Jones, are shown in somber beiges, maroons, and olive green.

Music is important throughout I Am Young, with Dean altering her color palette and graphic style to match her other characters’ very distinct musical tastes and eras, along with the each story’s plot line. Miriam and George’s Beatlemania is shown in black-and-white, while Lisa’s later psychedelic tripping to the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds is depicted in deep pink, gold, and green swirls. High school seniors and best friends Kennedy and Rhea, whose growing differences are summed up in their opposing views of pop singer Tom Jones, are shown in somber beiges, maroons, and olive green.

Dean smartly varies the size and shape of panels in these stories, sometimes omitting panel frames all together, to accentuate mood and events. Similarly, she makes some pages very busy or empty, with text sometimes centered or even omitted, in telling ways. When Roberta in “Baby Fat” begins to doubt that she really was ready at 18 to marry Pepe, we see her in the corner of a page, vulnerably small against a large vista. When she unwillingly derives some comfort from returning to her childhood home, Roberta is almost overwhelmed by parental concern along with her own doubts, shown nearly smothered by the busy patterns of a subdued blue quilt.

Dean smartly varies the size and shape of panels in these stories, sometimes omitting panel frames all together, to accentuate mood and events. Similarly, she makes some pages very busy or empty, with text sometimes centered or even omitted, in telling ways. When Roberta in “Baby Fat” begins to doubt that she really was ready at 18 to marry Pepe, we see her in the corner of a page, vulnerably small against a large vista. When she unwillingly derives some comfort from returning to her childhood home, Roberta is almost overwhelmed by parental concern along with her own doubts, shown nearly smothered by the busy patterns of a subdued blue quilt.

Throughout this visually rich and emotionally wise book, Dean continues to question crushes and how we see others and ourselves. In “Nana,” the central character continues to doubt herself harshly, but she realizes that a shared love of Karen Carpenter’s music is not enough for a former school bully to become a new, close friend. In “Alvin,” the brainy central character has a retro appreciation for Chuck Berry, but that and all the theories he knows about social injustice cannot get him a date for his high school’s “sock hop.” Alvin is left alone, with a migraine headache. M. Dean cumulatively fulfills her goals for this graphic work in each story. In an interview, she said, “I want to tell stories about the foibles of youth, the mistakes and nuances, the people, places, and things that feel important.” Dean added, “I realized a title like I Am Young reveals both naivete and an acknowledgement that everyone grows older and changes.”

Throughout this visually rich and emotionally wise book, Dean continues to question crushes and how we see others and ourselves. In “Nana,” the central character continues to doubt herself harshly, but she realizes that a shared love of Karen Carpenter’s music is not enough for a former school bully to become a new, close friend. In “Alvin,” the brainy central character has a retro appreciation for Chuck Berry, but that and all the theories he knows about social injustice cannot get him a date for his high school’s “sock hop.” Alvin is left alone, with a migraine headache. M. Dean cumulatively fulfills her goals for this graphic work in each story. In an interview, she said, “I want to tell stories about the foibles of youth, the mistakes and nuances, the people, places, and things that feel important.” Dean added, “I realized a title like I Am Young reveals both naivete and an acknowledgement that everyone grows older and changes.”

Readers who are mature enough to take an objective view of crushes vs. adult  relationships or who enjoy music and art will take particular pleasure in Dean’s storytelling achievements here. I also believe that those of us old enough to remember the Beatles’ 1960s debuts in Britain and the U.S. will find much to be nostalgic about in I Am Young, even as I ruefully wonder if some young readers (or perhaps the tween characters in Crush) might mistake the circular vinyl record and record album covers Dean depicts for CDs! In these days of streaming music, perhaps CDs will soon lose their familiarity as well.

relationships or who enjoy music and art will take particular pleasure in Dean’s storytelling achievements here. I also believe that those of us old enough to remember the Beatles’ 1960s debuts in Britain and the U.S. will find much to be nostalgic about in I Am Young, even as I ruefully wonder if some young readers (or perhaps the tween characters in Crush) might mistake the circular vinyl record and record album covers Dean depicts for CDs! In these days of streaming music, perhaps CDs will soon lose their familiarity as well.

As someone who no longer says, “I am young” but still very much appreciates  exchanging valentines with my white-haired husband, I find the final double spread pages of M. Dean’s novel particularly meaningful. On the left, we see aged Miriam and George, now barely old acquaintances, while on the right we see the couple as they first met, teenagers sitting together, with handwritten greetings to one another at the top and bottom of the page. There is something to be said for memories and being young at heart—and M. Dean captures it here.

exchanging valentines with my white-haired husband, I find the final double spread pages of M. Dean’s novel particularly meaningful. On the left, we see aged Miriam and George, now barely old acquaintances, while on the right we see the couple as they first met, teenagers sitting together, with handwritten greetings to one another at the top and bottom of the page. There is something to be said for memories and being young at heart—and M. Dean captures it here.

At the start of a new year, in our sometimes Kafkaesque world, it is good to realize that not all tales from the inner city are bad. What exactly do I mean by that remark? I hope you will be amused that it contains the titles of two new graphic story collections I am about to discuss. Today I look at works by master storytellers Peter Kuper and Shaun Tan, whose award-winning achievements I have reviewed before. Some earlier works by both artist/illustrators are discussed

At the start of a new year, in our sometimes Kafkaesque world, it is good to realize that not all tales from the inner city are bad. What exactly do I mean by that remark? I hope you will be amused that it contains the titles of two new graphic story collections I am about to discuss. Today I look at works by master storytellers Peter Kuper and Shaun Tan, whose award-winning achievements I have reviewed before. Some earlier works by both artist/illustrators are discussed Words, though sparsely used, are integral to Peter Kuper’s Kafkaesque: Fourteen Stories (2018). On the book’s frontispiece, Kuper describes this work as a “conversation with [Franz] Kafka.’’ This Czech author (1883 – 1924) wrote such powerful novels and stories depicting the absurdities of government and cruel circumstances of people’s lives– including The Trial, The Castle, and The Metamorphosis—that his name has become a synonym for nightmarish bureaucracy—“Kafkaesque.”

Words, though sparsely used, are integral to Peter Kuper’s Kafkaesque: Fourteen Stories (2018). On the book’s frontispiece, Kuper describes this work as a “conversation with [Franz] Kafka.’’ This Czech author (1883 – 1924) wrote such powerful novels and stories depicting the absurdities of government and cruel circumstances of people’s lives– including The Trial, The Castle, and The Metamorphosis—that his name has become a synonym for nightmarish bureaucracy—“Kafkaesque.”

character in “Before the Law,” even as we see him initially questioning the guard who will not let him enter an important government building. Kuper’s making this seemingly powerless figure a Black man adds another layer of meaning to this “conversation with Kafka.” The years-long fictional exchange here, portrayed in a two-page double spread swirl of images, ends ironically, with the guard’s revealing that this entrance was always meant for the now dying, too patient character. He never tried to force his way past the guard. Readers may well wonder about our own life choices and whether or when it is wise to delay action. Like most of the stories in Kafkaeque, these are only five or six pages long.

character in “Before the Law,” even as we see him initially questioning the guard who will not let him enter an important government building. Kuper’s making this seemingly powerless figure a Black man adds another layer of meaning to this “conversation with Kafka.” The years-long fictional exchange here, portrayed in a two-page double spread swirl of images, ends ironically, with the guard’s revealing that this entrance was always meant for the now dying, too patient character. He never tried to force his way past the guard. Readers may well wonder about our own life choices and whether or when it is wise to delay action. Like most of the stories in Kafkaeque, these are only five or six pages long. Two of Franz Kafka’s best-known short works, though, receive lengthier interpretations. Kuper devotes 22 pages to “A Hunger Artist” and 45 pages to “In the Penal Colony.” These sobering, thought-provoking stories about what spectacles people watch and what measures our judicial systems consider to be justice raise multifaceted questions. They touch on human nature in general but are also highly relevant to today’s social media-driven world and to current issues in U.S. judicial reform. Here, as is typical in Kuper’s work, panel size and shape vary to emphasize the mood of each story element. Similarly, Kuper’s exaggerated abstraction of facial features and body language dramatizes his sympathy with Kafka’s nightmarish views.

Two of Franz Kafka’s best-known short works, though, receive lengthier interpretations. Kuper devotes 22 pages to “A Hunger Artist” and 45 pages to “In the Penal Colony.” These sobering, thought-provoking stories about what spectacles people watch and what measures our judicial systems consider to be justice raise multifaceted questions. They touch on human nature in general but are also highly relevant to today’s social media-driven world and to current issues in U.S. judicial reform. Here, as is typical in Kuper’s work, panel size and shape vary to emphasize the mood of each story element. Similarly, Kuper’s exaggerated abstraction of facial features and body language dramatizes his sympathy with Kafka’s nightmarish views.  Shaun Tan’s Tales from the Inner City (2018) is more varied in tone than Kafkaesque, but it too contains dark elements as it explores the relationships among animals and supposedly superior human beings. The 25 prose poems and short stories here are Tan’s “sister volume” to his earlier collection of 15 illustrated short pieces, Tales from Outer Suburbia (2009). In both these works, it is the illustrations that will speak most eloquently to readers of all ages. Tan’s stories in this latest volume, though, seem geared to a tween on up audience.

Shaun Tan’s Tales from the Inner City (2018) is more varied in tone than Kafkaesque, but it too contains dark elements as it explores the relationships among animals and supposedly superior human beings. The 25 prose poems and short stories here are Tan’s “sister volume” to his earlier collection of 15 illustrated short pieces, Tales from Outer Suburbia (2009). In both these works, it is the illustrations that will speak most eloquently to readers of all ages. Tan’s stories in this latest volume, though, seem geared to a tween on up audience. As he has explained on his

As he has explained on his  inspire the final visual piece, in each instance here a full-color painting. Sometimes Tan photographed real-life places, gaining naturalistic details, while at other points, his own drawings or “doodles” were his visual inspiration. One illustration—of a deer on the upper floor of a skyscraper—even early on was a diorama, populated by stand-up figures Tan made! The author built clay-and-plaster models for another painted illustration here, that of fish with almost human faces.

inspire the final visual piece, in each instance here a full-color painting. Sometimes Tan photographed real-life places, gaining naturalistic details, while at other points, his own drawings or “doodles” were his visual inspiration. One illustration—of a deer on the upper floor of a skyscraper—even early on was a diorama, populated by stand-up figures Tan made! The author built clay-and-plaster models for another painted illustration here, that of fish with almost human faces.  Giant snails on a city bridge; a leaping fox in a sleeper’s bedroom; in an echo of Kafkaesque legal systems, a bear with its lawyer lumbering up courthouse steps—these eerie images are memorable and thought-provoking. Yet it is Tan’s longer works centering on dogs and cats that also touch one’s heartstrings. A series of 13 wordless, double spread paintings depict the

Giant snails on a city bridge; a leaping fox in a sleeper’s bedroom; in an echo of Kafkaesque legal systems, a bear with its lawyer lumbering up courthouse steps—these eerie images are memorable and thought-provoking. Yet it is Tan’s longer works centering on dogs and cats that also touch one’s heartstrings. A series of 13 wordless, double spread paintings depict the  long history of human-canine interaction while also referencing the devotion of dogs to their humans. The short poems that accompany these paintings highlight the sad reality that dog lives are so much shorter than human ones—people will inevitably experience the loss of this bond. As Tan writes, “And when you died I took you down to the river. And when I died you waited for me by the shore. So it was that time passed between us.”

long history of human-canine interaction while also referencing the devotion of dogs to their humans. The short poems that accompany these paintings highlight the sad reality that dog lives are so much shorter than human ones—people will inevitably experience the loss of this bond. As Tan writes, “And when you died I took you down to the river. And when I died you waited for me by the shore. So it was that time passed between us.” In a parallel twist on this theme, Tan illustrates a cat loss story with a painting of a literally absurd but emotionally-true situation. Just as the death of their cat has rescued a woman from frozen emotions, allowing her to shed tears as she grieves with other bereft cat “owners,” we see a giant cat rescuing its people. The woman and her young daughter sit on the now gigantic cat’s head, kept safely above a sea of crashing waves. Her newly-found ocean of tears will not capsize this mother with grief. Tales from the Inner City is full of such moving images, sometimes provoking sentimental as well as sharply-questioning responses.

In a parallel twist on this theme, Tan illustrates a cat loss story with a painting of a literally absurd but emotionally-true situation. Just as the death of their cat has rescued a woman from frozen emotions, allowing her to shed tears as she grieves with other bereft cat “owners,” we see a giant cat rescuing its people. The woman and her young daughter sit on the now gigantic cat’s head, kept safely above a sea of crashing waves. Her newly-found ocean of tears will not capsize this mother with grief. Tales from the Inner City is full of such moving images, sometimes provoking sentimental as well as sharply-questioning responses.  Metamorphosis (2004). It already appears in some high schools’ curriculum. For an overview of Kuper’s works, including the more light-heartedly satirical “Spy vs. Spy” pieces he has created for Mad magazine, readers can browse the author/illustrator’s

Metamorphosis (2004). It already appears in some high schools’ curriculum. For an overview of Kuper’s works, including the more light-heartedly satirical “Spy vs. Spy” pieces he has created for Mad magazine, readers can browse the author/illustrator’s  Giving “experiences” rather than “things” is a trend this winter holiday season, making graphic literature a fashionable, two-for-one joy for the tween-and-up readers on your gift list. They can hold a volume in their hands, actively scanning between text and images, flipping back-and-forth between pages, as they mull over and revel in how a great graphic work builds its many layers of meaning. I have two sumptuous books to recommend this month, works that will move hearts and minds even as their rich imagery and high-quality production values satisfy hands and eyes. One will even tickle funny-bones as it is read and reread . . . . These recently published novels have already been acclaimed among this year’s potential award winners.

Giving “experiences” rather than “things” is a trend this winter holiday season, making graphic literature a fashionable, two-for-one joy for the tween-and-up readers on your gift list. They can hold a volume in their hands, actively scanning between text and images, flipping back-and-forth between pages, as they mull over and revel in how a great graphic work builds its many layers of meaning. I have two sumptuous books to recommend this month, works that will move hearts and minds even as their rich imagery and high-quality production values satisfy hands and eyes. One will even tickle funny-bones as it is read and reread . . . . These recently published novels have already been acclaimed among this year’s potential award winners. The Assassination of Brangwain Spurge (2018), written by M.T. Anderson and illustrated by Eugene Yelchin, uses humor and the traditions of fantasy fiction to comment slyly on real-world politics and problems. Its central characters are elves and goblins, at war with each other for a thousand years, whose different takes on that history and mistaken ideas about one another mirror more than a few conflicts today. When elf Gawain, a timid historian, is drafted to be the ambassador to the goblin kingdom—and ordered to spy on the goblins as well, the fun begins. How Gawain interacts with his goblin host Werfel and his distant elven spymaster Lord Clivers is the central plot here, one packed with breathless action and escapes as well as scenes of daily goblin life and high court pomp. Goblin habits are, by human standards, often gross! Young readers and others merely young-at-heart will enjoy details there, including the behavior of Werfel’s affectionate pet—a flying, fishlike creature with tentacles. But it the way Anderson and Yelchin tell this story that makes this book such a gem.

The Assassination of Brangwain Spurge (2018), written by M.T. Anderson and illustrated by Eugene Yelchin, uses humor and the traditions of fantasy fiction to comment slyly on real-world politics and problems. Its central characters are elves and goblins, at war with each other for a thousand years, whose different takes on that history and mistaken ideas about one another mirror more than a few conflicts today. When elf Gawain, a timid historian, is drafted to be the ambassador to the goblin kingdom—and ordered to spy on the goblins as well, the fun begins. How Gawain interacts with his goblin host Werfel and his distant elven spymaster Lord Clivers is the central plot here, one packed with breathless action and escapes as well as scenes of daily goblin life and high court pomp. Goblin habits are, by human standards, often gross! Young readers and others merely young-at-heart will enjoy details there, including the behavior of Werfel’s affectionate pet—a flying, fishlike creature with tentacles. But it the way Anderson and Yelchin tell this story that makes this book such a gem.  Gawain is a hybrid graphic novel—one that intersperses pages of prose with pages of wordless images which themselves advance its story-telling. (I have written about other hybrid graphic novels, including

Gawain is a hybrid graphic novel—one that intersperses pages of prose with pages of wordless images which themselves advance its story-telling. (I have written about other hybrid graphic novels, including  Award-winning illustrator Yelchin inventively styles these imagined views as Renaissance engravings, in the vein of Albrecht Durer’s woodcuts. There are more than 180 pages of black-and-white images in this 500 page book, with changes in perspective and distance advancing fast-paced action even as other scenes contain so many humorous, clever details that the eye lingers. Readers may well page back to see and savor more—I know I did. Yelchin gives characters here such distinctive facial emotions and body language that we empathize with these cartoonish characters’ woes even as their antics make us smile.

Award-winning illustrator Yelchin inventively styles these imagined views as Renaissance engravings, in the vein of Albrecht Durer’s woodcuts. There are more than 180 pages of black-and-white images in this 500 page book, with changes in perspective and distance advancing fast-paced action even as other scenes contain so many humorous, clever details that the eye lingers. Readers may well page back to see and savor more—I know I did. Yelchin gives characters here such distinctive facial emotions and body language that we empathize with these cartoonish characters’ woes even as their antics make us smile. Anderson’s language will also delight those readers who appreciate the somewhat old-fashioned, formal language of traditional fantasy epics, also when appropriate switched out to other verbal styles. The “broken Elvish” some Goblin nobles try to speak is a hoot: one enthusiastically invites Gawain into her home by saying “I punch you with me house hard, many time.” The book trailer for The Assassination of Gawain Spurge, which concludes with Anderson and Yelchin pretending to bicker about their collaboration, captures the tone as well as the content of this work.

Anderson’s language will also delight those readers who appreciate the somewhat old-fashioned, formal language of traditional fantasy epics, also when appropriate switched out to other verbal styles. The “broken Elvish” some Goblin nobles try to speak is a hoot: one enthusiastically invites Gawain into her home by saying “I punch you with me house hard, many time.” The book trailer for The Assassination of Gawain Spurge, which concludes with Anderson and Yelchin pretending to bicker about their collaboration, captures the tone as well as the content of this work.  Vesper Stamper’s richly-illustrated novel What the Night Sings (2018) is more serious in tone. Focusing on the Holocaust experiences and survival of 16- year old Gerta Rausch, a German-Jewish musician, this powerful work is both moving and uplifting. Illustrator/author Stamper, herself born in Germany but raised in New York City, shows in images and words how profoundly resilient the human spirit is. At first, a younger Gerta is sheltered by her musician father and the opera star who mothers her; Gerta does not even know that she is Jewish! But their family is betrayed, and Gerta and her father herded into concentration camps. He does not survive. Gerta is near death when victorious Allied troops rescue her as they liberate prisoners at Auschwitz. (Some prior knowledge of the era might be helpful for tween readers, though When the Night Sings may also serve as sobering introduction, raising important questions.)

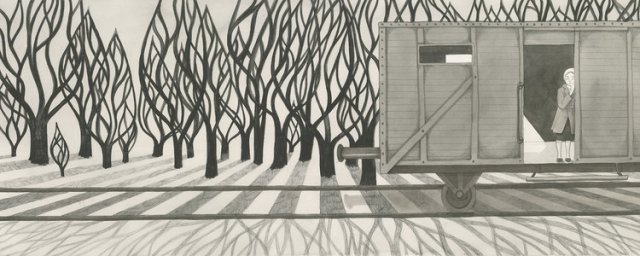

Vesper Stamper’s richly-illustrated novel What the Night Sings (2018) is more serious in tone. Focusing on the Holocaust experiences and survival of 16- year old Gerta Rausch, a German-Jewish musician, this powerful work is both moving and uplifting. Illustrator/author Stamper, herself born in Germany but raised in New York City, shows in images and words how profoundly resilient the human spirit is. At first, a younger Gerta is sheltered by her musician father and the opera star who mothers her; Gerta does not even know that she is Jewish! But their family is betrayed, and Gerta and her father herded into concentration camps. He does not survive. Gerta is near death when victorious Allied troops rescue her as they liberate prisoners at Auschwitz. (Some prior knowledge of the era might be helpful for tween readers, though When the Night Sings may also serve as sobering introduction, raising important questions.) Gerta slowly rediscovers her singing voice and finds love in a displaced person camp, later marrying and immigrating with her new husband to Israel. Simple sentences, each word aptly chosen, are rich with metaphor as they communicate teen-aged Gerta’s thoughts: She realizes that her musician father’s viola, which she has managed to save, “is a forest. It is a living tree. It is the heartwood of our family.” This refrain is also seen in images throughout the book, where trees shown first as abstract, barren roots, trunks, and limbs gradually thrive and blossom. Gerta herself is sometimes shown in impossible, symbolic juxtaposition to these backgrounds, rather than realistically.

Gerta slowly rediscovers her singing voice and finds love in a displaced person camp, later marrying and immigrating with her new husband to Israel. Simple sentences, each word aptly chosen, are rich with metaphor as they communicate teen-aged Gerta’s thoughts: She realizes that her musician father’s viola, which she has managed to save, “is a forest. It is a living tree. It is the heartwood of our family.” This refrain is also seen in images throughout the book, where trees shown first as abstract, barren roots, trunks, and limbs gradually thrive and blossom. Gerta herself is sometimes shown in impossible, symbolic juxtaposition to these backgrounds, rather than realistically. reappear later in this poignantly illustrated volume, in scenes which range from sorrow to hope and joy. Stamper depicts her characters’ many emotional and literal journeys in varied visual formats: quarter-page as well as full page or double spread illustrations, along with a dozen spot illustrations, all embody significant moments or emotions. Their muted palette of grey and sepia ink washes is as haunting as the sparse eloquence of Gerta’s religious husband-to-be Lev, also liberated at

reappear later in this poignantly illustrated volume, in scenes which range from sorrow to hope and joy. Stamper depicts her characters’ many emotional and literal journeys in varied visual formats: quarter-page as well as full page or double spread illustrations, along with a dozen spot illustrations, all embody significant moments or emotions. Their muted palette of grey and sepia ink washes is as haunting as the sparse eloquence of Gerta’s religious husband-to-be Lev, also liberated at  Auschwitz, who says, “The way I love you . . . It’s like music. It’s like praying.” Lev and Gerta relate to traditional Judaism in very different, yet ultimately complementary ways, as Stamper reveals through luminous words as well as images. I was not surprised to read in an

Auschwitz, who says, “The way I love you . . . It’s like music. It’s like praying.” Lev and Gerta relate to traditional Judaism in very different, yet ultimately complementary ways, as Stamper reveals through luminous words as well as images. I was not surprised to read in an  readers will welcome. It contains information about events in Stamper’s life leading to that degree as well details of her Holocaust research, including photographs. A relevant map, glossary, and suggested further resources conclude this hardcover volume, printed on high-quality, heavy stock paper, enhancing the depth of shaded illustrations and further distinguishing it as a special, “giftable” volume.

readers will welcome. It contains information about events in Stamper’s life leading to that degree as well details of her Holocaust research, including photographs. A relevant map, glossary, and suggested further resources conclude this hardcover volume, printed on high-quality, heavy stock paper, enhancing the depth of shaded illustrations and further distinguishing it as a special, “giftable” volume. Santa Claus may not be this season’s biggest holiday myth. A more troubling fantasy here in North America may be the myth of the perfectly happy, affluent family—one celebrating its winter holidays with big smiles in a bright, cheerful home filled with presents. The many ads and other images featuring such families can be a far cry from what some kids and teens actually experience. Today, I look at two graphic works—one a personal memoir and the other a novel—that vividly depict real-life family problems as these play out during holidays as well as ordinary days. Addiction is the main problem in both books. Readers teen and up will appreciate how the central figures in these works cope with and survive family woes and, in one case, even win a bright future.

Santa Claus may not be this season’s biggest holiday myth. A more troubling fantasy here in North America may be the myth of the perfectly happy, affluent family—one celebrating its winter holidays with big smiles in a bright, cheerful home filled with presents. The many ads and other images featuring such families can be a far cry from what some kids and teens actually experience. Today, I look at two graphic works—one a personal memoir and the other a novel—that vividly depict real-life family problems as these play out during holidays as well as ordinary days. Addiction is the main problem in both books. Readers teen and up will appreciate how the central figures in these works cope with and survive family woes and, in one case, even win a bright future.  Author/illustrator Jarrett J. Krosoczka dedicated his recent memoir Hey, Kiddo: How I Lost My Mother, Found My Father, and Dealt with Family Addiction (2018) not only to his grandparents and mother but to “every reader who recognizes this experience.” Teens who know 41 year-old Krosoczka only as the

Author/illustrator Jarrett J. Krosoczka dedicated his recent memoir Hey, Kiddo: How I Lost My Mother, Found My Father, and Dealt with Family Addiction (2018) not only to his grandparents and mother but to “every reader who recognizes this experience.” Teens who know 41 year-old Krosoczka only as the  following year. Throughout this memoir, which follows Jarrett through high school graduation at age seventeen, holidays figure prominently: Halloween, Thanksgiving, and Mother’s Day are fraught with meaning and tension. Traditional Mother’s Day cards suit neither the love and disappointment of his relationship with mother Leslie nor the complicated devotion grandmother Shirley provides. It is sometimes hard for bitter-tongued Shirley to see beyond her own needs and beliefs, as when she dismisses the portrait teen-aged Jarrett has labored over for his grandparents’ 45th wedding anniversary gift. Her saying “It doesn’t look anything like us. You’re not that good” is terribly hurtful to him.

following year. Throughout this memoir, which follows Jarrett through high school graduation at age seventeen, holidays figure prominently: Halloween, Thanksgiving, and Mother’s Day are fraught with meaning and tension. Traditional Mother’s Day cards suit neither the love and disappointment of his relationship with mother Leslie nor the complicated devotion grandmother Shirley provides. It is sometimes hard for bitter-tongued Shirley to see beyond her own needs and beliefs, as when she dismisses the portrait teen-aged Jarrett has labored over for his grandparents’ 45th wedding anniversary gift. Her saying “It doesn’t look anything like us. You’re not that good” is terribly hurtful to him.  spotlighted by its placement on a double spread page with a black background. Such double spreads highlight other emotionally significant moments in this eight-chapter, 300-page work. We also see how some parental patterns have unintentional influences. Shirley and Joe themselves drink heavily, leading to household arguments. On a lighter note, Joe’s affectionate hello to Jarrett, “Hey, Kiddo,” is echoed by Leslie in some of the letters she writes to her son when she is (unbeknown to him) in prison. Jarrett Krosoczka as author does a great job capturing and reproducing the rhythms of everyday, idiosyncratic, and sometimes profane speech.

spotlighted by its placement on a double spread page with a black background. Such double spreads highlight other emotionally significant moments in this eight-chapter, 300-page work. We also see how some parental patterns have unintentional influences. Shirley and Joe themselves drink heavily, leading to household arguments. On a lighter note, Joe’s affectionate hello to Jarrett, “Hey, Kiddo,” is echoed by Leslie in some of the letters she writes to her son when she is (unbeknown to him) in prison. Jarrett Krosoczka as author does a great job capturing and reproducing the rhythms of everyday, idiosyncratic, and sometimes profane speech.  ornament. Readers never lose track of where we are in this memoir, while Krosoczka catches us up on subsequent events in an affecting final “Author’s Note.” The following “Note on the Art” is where we learn the origin of the book’s limited color scheme—a tribute to his grandfather Joe. Krosoczka at age 41 concludes his heartfelt memoir with images supporting his recognition that Joe and Shirley were “two incredible parents right there before me the entire time. They just happened to be a generation removed.” I myself find it moving that this echoes the dedication of his first published book, Goodnight, Monkey Boy (2001). Even back then, the 23 year old author/illustrator acknowledged “Grandma and Grandpa, the best parents a kid could ask for.”

ornament. Readers never lose track of where we are in this memoir, while Krosoczka catches us up on subsequent events in an affecting final “Author’s Note.” The following “Note on the Art” is where we learn the origin of the book’s limited color scheme—a tribute to his grandfather Joe. Krosoczka at age 41 concludes his heartfelt memoir with images supporting his recognition that Joe and Shirley were “two incredible parents right there before me the entire time. They just happened to be a generation removed.” I myself find it moving that this echoes the dedication of his first published book, Goodnight, Monkey Boy (2001). Even back then, the 23 year old author/illustrator acknowledged “Grandma and Grandpa, the best parents a kid could ask for.”  David Small, a Caldecott Award-winning children’s book illustrator, won further acclaim and awards in 2010 for his own painful graphic memoir, Stitches (2009), detailing his youth and dysfunctional family life in 1950s America. Small’s new graphic novel, though, titled Home After Dark (2018), is a fictional work set in the same time and milieu, but based on experiences told to the author/illustrator by a friend. This harshly poetic book is a breath-taking achievement!

David Small, a Caldecott Award-winning children’s book illustrator, won further acclaim and awards in 2010 for his own painful graphic memoir, Stitches (2009), detailing his youth and dysfunctional family life in 1950s America. Small’s new graphic novel, though, titled Home After Dark (2018), is a fictional work set in the same time and milieu, but based on experiences told to the author/illustrator by a friend. This harshly poetic book is a breath-taking achievement!  with no words at all. Russell is abandoned by his mother and later by his alcoholic father, set adrift in a small California town. This community is rife with school yard bullies, racist attitudes towards Asian immigrants, homophobia, and sexual stereotypes that make “girl” a slur when spoken to or about any teen age boy. Russell cannot even escape in sleep, as his fears and experiences transmogrify into frightening dreams. One dream transforms his limited understanding of the town business men’s Lions Club into a circus where Russell finds himself thrown into an actual lion’s cage. In a devastating image, Small draws the terrified teen crouched inside the lion’s wide-open jaws.

with no words at all. Russell is abandoned by his mother and later by his alcoholic father, set adrift in a small California town. This community is rife with school yard bullies, racist attitudes towards Asian immigrants, homophobia, and sexual stereotypes that make “girl” a slur when spoken to or about any teen age boy. Russell cannot even escape in sleep, as his fears and experiences transmogrify into frightening dreams. One dream transforms his limited understanding of the town business men’s Lions Club into a circus where Russell finds himself thrown into an actual lion’s cage. In a devastating image, Small draws the terrified teen crouched inside the lion’s wide-open jaws.  Yet there is also some hope here. Russell, who near the book’s conclusion says “I am nobody’s son,” is taken in by the Chinese immigrant family whose trust he has already betrayed once. The final page and image is of Mrs. Wah, calling Russell into their house, with the welcoming words that “Supper is ready.” For a teen who has despaired of life, summing up his biggest, seemingly insurmountable problem as his wish “to live without hurting anyone,” a second chance in that circumscribed, pre-Internet world now seems possible. Teen readers might want or need to talk about this book with others, for background insight into the era as well as discussion of the novel’s events and ideas. Home After Dark is well worth that commitment of time and energy for readers ready to explore the many issues, including alcoholism, it addresses.

Yet there is also some hope here. Russell, who near the book’s conclusion says “I am nobody’s son,” is taken in by the Chinese immigrant family whose trust he has already betrayed once. The final page and image is of Mrs. Wah, calling Russell into their house, with the welcoming words that “Supper is ready.” For a teen who has despaired of life, summing up his biggest, seemingly insurmountable problem as his wish “to live without hurting anyone,” a second chance in that circumscribed, pre-Internet world now seems possible. Teen readers might want or need to talk about this book with others, for background insight into the era as well as discussion of the novel’s events and ideas. Home After Dark is well worth that commitment of time and energy for readers ready to explore the many issues, including alcoholism, it addresses.  I plan now to decompress from Home After Dark by reading as many of the ten Lunch Lady graphic novels as are available in my local library! I have only personally read her adventures in a series of compilation volumes, the Comics Squad books, which Jarrett Krosocska contributed to as well as co-edited. (I reviewed one a few years ago

I plan now to decompress from Home After Dark by reading as many of the ten Lunch Lady graphic novels as are available in my local library! I have only personally read her adventures in a series of compilation volumes, the Comics Squad books, which Jarrett Krosocska contributed to as well as co-edited. (I reviewed one a few years ago  reread my own copy of David Small’s searing memoir, Stitches. I will also remember to count each and every win as any woes arise. Fine graphic literature is definitely in my win column, along with family and friends, for whom I feel fortunate and remain grateful.

reread my own copy of David Small’s searing memoir, Stitches. I will also remember to count each and every win as any woes arise. Fine graphic literature is definitely in my win column, along with family and friends, for whom I feel fortunate and remain grateful. What do we tell school-aged children who see, read, or hear news about this past weekend’s massacre at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue? You already may have had to deal with initial reactions, but I have some print resources to offer—suggestions which may be helpful, depending on the ages and maturity of the children and your relationship (parent, teacher, librarian) to them.

What do we tell school-aged children who see, read, or hear news about this past weekend’s massacre at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue? You already may have had to deal with initial reactions, but I have some print resources to offer—suggestions which may be helpful, depending on the ages and maturity of the children and your relationship (parent, teacher, librarian) to them.  Two graphic novels published by the Anne Frank House in cooperation with the Resistance Museums of Friesland and Amsterdam help explain some of the causes—and horrible results—of 20th century anti-Semitism, unfortunately still pertinent today and so dramatically obvious this past weekend. A Family Secret (2007) and its sequel The Search (2007), both written and illustrated by Eric Heuvel (originally in Dutch) explore in well-researched and well-crafted form the origins and consequences of anti-Semitism made public policy by Adolph Hitler and his Nazi forces—not only in Germany but in the countries German forces conquered, often with the help of many complicit citizens there. The results of voting a bigoted despot into power and then going along with increasingly biased laws are dramatized in these novels in ways that will engage and enlighten young readers, even as they resonate loudly for adults. With an election facing us here in the United States in another week, it is important to remember that many of the most bloodthirsty political leaders of the last 100 years have, around the globe, gained power first as elected officials.

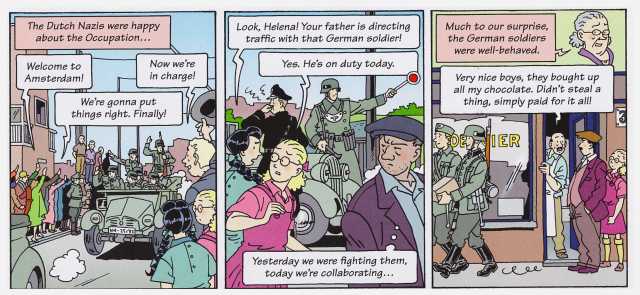

Two graphic novels published by the Anne Frank House in cooperation with the Resistance Museums of Friesland and Amsterdam help explain some of the causes—and horrible results—of 20th century anti-Semitism, unfortunately still pertinent today and so dramatically obvious this past weekend. A Family Secret (2007) and its sequel The Search (2007), both written and illustrated by Eric Heuvel (originally in Dutch) explore in well-researched and well-crafted form the origins and consequences of anti-Semitism made public policy by Adolph Hitler and his Nazi forces—not only in Germany but in the countries German forces conquered, often with the help of many complicit citizens there. The results of voting a bigoted despot into power and then going along with increasingly biased laws are dramatized in these novels in ways that will engage and enlighten young readers, even as they resonate loudly for adults. With an election facing us here in the United States in another week, it is important to remember that many of the most bloodthirsty political leaders of the last 100 years have, around the globe, gained power first as elected officials. Heuvel’s two graphic novels focus on the lives of two girls—German Jewish refugee Esther and Dutch Protestant Helena—neighbors from ages twelve through sixteen, starting in 1938, when Esther and her family arrive in Amsterdam. A Family Secret follows the girls through 1942, while The Search concentrates on events in their lives from 1942 onward. All these events are made even more immediate by being told through a contemporary, framing lens: We readers discover these stories at the same time that Helena’s twelve- or thirteen-year old grandson Jeroen does, going through mementos in his grandmother’s attic. It is through his curiosity and persistence that we not only learn about these past events but that Helena discovers that Esther (but not her parents) survived being arrested! The Search gives most attention to Esther’s (and other Nazi victims’) experiences under the Nazis and in World War II’s aftermath. Esther’s having found safety and a new life in the United States takes on poignant, new meaning now, just days after the Pittsburgh massacre.

Heuvel’s two graphic novels focus on the lives of two girls—German Jewish refugee Esther and Dutch Protestant Helena—neighbors from ages twelve through sixteen, starting in 1938, when Esther and her family arrive in Amsterdam. A Family Secret follows the girls through 1942, while The Search concentrates on events in their lives from 1942 onward. All these events are made even more immediate by being told through a contemporary, framing lens: We readers discover these stories at the same time that Helena’s twelve- or thirteen-year old grandson Jeroen does, going through mementos in his grandmother’s attic. It is through his curiosity and persistence that we not only learn about these past events but that Helena discovers that Esther (but not her parents) survived being arrested! The Search gives most attention to Esther’s (and other Nazi victims’) experiences under the Nazis and in World War II’s aftermath. Esther’s having found safety and a new life in the United States takes on poignant, new meaning now, just days after the Pittsburgh massacre.  Helena’s family’s reactions to the Nazi invaders runs the gamut: her father is a Dutch police man who dutifully if reluctantly follows Nazi orders to arrest Jews, while one of her brothers is active in the illegal Dutch resistance movement. We learn of Dutch individuals who aid Esther while others chase the bewildered, lone girl away. Some of their Amsterdam neighbors protest Nazi cruelty while more accept it, either out of reluctance to question authority, fear, or their own mistaken, anti-Semitic views. Through Esther’s accounts, we learn the ways in which these Dutch reactions are akin to some German ones, though the author and his museum expert sources do an excellent job further spotlighting how economic hardship and scapegoating of Jews in Germany contributed to Hitler’s election and continued support there.

Helena’s family’s reactions to the Nazi invaders runs the gamut: her father is a Dutch police man who dutifully if reluctantly follows Nazi orders to arrest Jews, while one of her brothers is active in the illegal Dutch resistance movement. We learn of Dutch individuals who aid Esther while others chase the bewildered, lone girl away. Some of their Amsterdam neighbors protest Nazi cruelty while more accept it, either out of reluctance to question authority, fear, or their own mistaken, anti-Semitic views. Through Esther’s accounts, we learn the ways in which these Dutch reactions are akin to some German ones, though the author and his museum expert sources do an excellent job further spotlighting how economic hardship and scapegoating of Jews in Germany contributed to Hitler’s election and continued support there.

Heralding Halloween, plastic ghosts and ghouls materialized on some front porches back in September. This horde will rapidly increase–adding movie monsters, comic book creatures, and graveyard trappings—as October 31 approaches. Yet the truly terrifying may not be what we see but what we can only imagine and dreadfully anticipate. This psychological truth is the reason that one graphic novel has haunted me for several years, since I first read it. Today I want to spotlight the chills found in Emily Carroll’s Through the Woods (2014), an eerie masterpiece with a profound understanding of mayhem and mystery, far beyond the jolly trick-or-treating or “haunted houses” of Halloween. Readers tween on up with a taste for the macabre will greatly appreciate this multiple-award winning work.

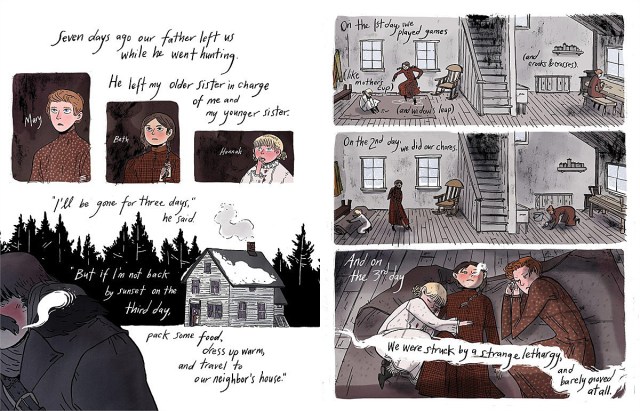

Heralding Halloween, plastic ghosts and ghouls materialized on some front porches back in September. This horde will rapidly increase–adding movie monsters, comic book creatures, and graveyard trappings—as October 31 approaches. Yet the truly terrifying may not be what we see but what we can only imagine and dreadfully anticipate. This psychological truth is the reason that one graphic novel has haunted me for several years, since I first read it. Today I want to spotlight the chills found in Emily Carroll’s Through the Woods (2014), an eerie masterpiece with a profound understanding of mayhem and mystery, far beyond the jolly trick-or-treating or “haunted houses” of Halloween. Readers tween on up with a taste for the macabre will greatly appreciate this multiple-award winning work.  This collection of five stories—one first created as a web comic by Canadian author/illustrator Carroll—is effectively bracketed by an introduction and a conclusion that are themselves scary tales. The introduction addresses a child’s fear of what monsters might lurk in the dark, while the conclusion reminds us that, even if Red Riding Hood escapes a wolf many times, the hungry wolf still only needs “enough luck” to find her “ONCE.” Here Carroll explicitly addresses the darkness underpinning many fairy-tale happy endings. Her story “A Lady’s Hands are Cold” is also a variant of a familiar tale, that of Bluebeard, the husband who marries woman after woman only to murder them. The other stories depict human or supernatural evils linked to everyday rather than fairy-tale events.

This collection of five stories—one first created as a web comic by Canadian author/illustrator Carroll—is effectively bracketed by an introduction and a conclusion that are themselves scary tales. The introduction addresses a child’s fear of what monsters might lurk in the dark, while the conclusion reminds us that, even if Red Riding Hood escapes a wolf many times, the hungry wolf still only needs “enough luck” to find her “ONCE.” Here Carroll explicitly addresses the darkness underpinning many fairy-tale happy endings. Her story “A Lady’s Hands are Cold” is also a variant of a familiar tale, that of Bluebeard, the husband who marries woman after woman only to murder them. The other stories depict human or supernatural evils linked to everyday rather than fairy-tale events.  “His Face All Red,” a jealous man kills his brother, but the slain man mysteriously reappears. (This is the only story with a male protagonist.) “My Friend Janna” shows what happens when the accomplice of a fake medium truly sees—or thinks she sees—real ghosts. “The Nesting Place,” the longest piece here, follows a young, recently-orphaned girl who goes to visit her adult brother and his fiancée. Beginning with the words “Belle’s mother had told her about monsters,” this story shows the horrifying, surprising ways the girl discovers some truths underlying that message. Yet these thumbnail plot sketches do not convey how and why this book is so powerful. It is Carroll’s visual artistry, an integral element in her storytelling choices, that makes Through the Woods such a memorable work.

“His Face All Red,” a jealous man kills his brother, but the slain man mysteriously reappears. (This is the only story with a male protagonist.) “My Friend Janna” shows what happens when the accomplice of a fake medium truly sees—or thinks she sees—real ghosts. “The Nesting Place,” the longest piece here, follows a young, recently-orphaned girl who goes to visit her adult brother and his fiancée. Beginning with the words “Belle’s mother had told her about monsters,” this story shows the horrifying, surprising ways the girl discovers some truths underlying that message. Yet these thumbnail plot sketches do not convey how and why this book is so powerful. It is Carroll’s visual artistry, an integral element in her storytelling choices, that makes Through the Woods such a memorable work.  dramatically positions any words and just one image in the center of a page, as a result making the surrounding, extensive black or white background another significant factor in the story’s emotional tone. This may be seen in the opening images, where a small blue figure is centered in a looming black forest, with a disproportionately large, blood-red sun dominating the stark white sky. The technique of creating a suspenseful, ominous tone is also evident in “His Face All Red,” as the bewildered killer travels deep underground to see what if anything has happened to his brother’s body.

dramatically positions any words and just one image in the center of a page, as a result making the surrounding, extensive black or white background another significant factor in the story’s emotional tone. This may be seen in the opening images, where a small blue figure is centered in a looming black forest, with a disproportionately large, blood-red sun dominating the stark white sky. The technique of creating a suspenseful, ominous tone is also evident in “His Face All Red,” as the bewildered killer travels deep underground to see what if anything has happened to his brother’s body. on the page, while word balloons trail like smoke or a mysterious, ghostly melody across pages and through scenes. At several points in this volume, notably in ”A Lady’s Hands Are Cold” and “In Conclusion,” word balloons have appropriately startling, blood-red backgrounds instead of the more typical white or black. In an interview, Carroll has

on the page, while word balloons trail like smoke or a mysterious, ghostly melody across pages and through scenes. At several points in this volume, notably in ”A Lady’s Hands Are Cold” and “In Conclusion,” word balloons have appropriately startling, blood-red backgrounds instead of the more typical white or black. In an interview, Carroll has  never fully displayed, just suggested. For instance, we learn on the last page of “Our Neighbor’s House” that the neighbor “IS NO MAN,” but we are not shown or told what kind of creature he is. Similarly, on the final pages of “In Conclusion,” we see only the wolf’s frightening eyes and teeth, not his full face or figure. What we imagine here, what is unknown, looms larger in the imagination just because of what we do not see. In the same way, the final terrifying page of “The Nesting Place” is especially horrible because we see only an ambiguous bit of what is now monstrous in young Belle’s life.

never fully displayed, just suggested. For instance, we learn on the last page of “Our Neighbor’s House” that the neighbor “IS NO MAN,” but we are not shown or told what kind of creature he is. Similarly, on the final pages of “In Conclusion,” we see only the wolf’s frightening eyes and teeth, not his full face or figure. What we imagine here, what is unknown, looms larger in the imagination just because of what we do not see. In the same way, the final terrifying page of “The Nesting Place” is especially horrible because we see only an ambiguous bit of what is now monstrous in young Belle’s life. For those who savor Through the Woods—or for those shy of horror or readers a bit too young for Carroll’s full-on macabre ambiguity—Baba Yaga’s Assistant (2015), written by Marika McCoola and illustrated Emily Carroll will be a lower-stress treat. Carroll had fun, as she notes on the book’s flyleaf, drawing that Russian folk tale’s “old crone full of riddles, rocks, and countless pointy teeth,” but the novel itself is about conquering one’s fears and resentments. Specifically, this fantasy graphic novel deals in an upbeat way with a young teen’s learning how to be part of a blended family with a stepmother and stepsister.

For those who savor Through the Woods—or for those shy of horror or readers a bit too young for Carroll’s full-on macabre ambiguity—Baba Yaga’s Assistant (2015), written by Marika McCoola and illustrated Emily Carroll will be a lower-stress treat. Carroll had fun, as she notes on the book’s flyleaf, drawing that Russian folk tale’s “old crone full of riddles, rocks, and countless pointy teeth,” but the novel itself is about conquering one’s fears and resentments. Specifically, this fantasy graphic novel deals in an upbeat way with a young teen’s learning how to be part of a blended family with a stepmother and stepsister.  I myself am eagerly awaiting a library copy of the recent graphic version of Laurie Halse Anderson’s award-winning novel, Speak (1999). That powerful work about rape and recovering from rape has been reissued with illustrations by Emily Carroll as Speak: The Graphic Novel (2018). Author Anderson wrote the script for this release, coordinating with Carroll through their editors, and praises the illustrations. Anderson notes that Carroll’s “ability to create tension is masterful.” The author adds that Carroll’s art gives readers “more perspective on the intensity of the emotion” the main character experiences. Anderson pays tribute to Carroll, eloquently summing up her contribution her by saying, “The addition of the art turns a haunting melody into a resonating chord.”

I myself am eagerly awaiting a library copy of the recent graphic version of Laurie Halse Anderson’s award-winning novel, Speak (1999). That powerful work about rape and recovering from rape has been reissued with illustrations by Emily Carroll as Speak: The Graphic Novel (2018). Author Anderson wrote the script for this release, coordinating with Carroll through their editors, and praises the illustrations. Anderson notes that Carroll’s “ability to create tension is masterful.” The author adds that Carroll’s art gives readers “more perspective on the intensity of the emotion” the main character experiences. Anderson pays tribute to Carroll, eloquently summing up her contribution her by saying, “The addition of the art turns a haunting melody into a resonating chord.”  Have you been busy calming your young people’s new school or classroom jitters? In my senior citizen circles, this duty falls to grandparents as well as parents and school staff. It can be even more frightening or puzzling for students new to a country as well as a school—and more complicated for the families and other adults who want to help them. (These difficulties are now exponentially worse for folks affected by President Trump’s immigration policies mandating zero tolerance and family separation.) Today I look at two picture books and a graphic novel full of wise, loving insights into the problems and joys of immigrant generations within families. While these three recent works are about Vietnamese and Thai immigrants to the United States, their sharp observations extend beyond any one ethnicity or particular national borders.

Have you been busy calming your young people’s new school or classroom jitters? In my senior citizen circles, this duty falls to grandparents as well as parents and school staff. It can be even more frightening or puzzling for students new to a country as well as a school—and more complicated for the families and other adults who want to help them. (These difficulties are now exponentially worse for folks affected by President Trump’s immigration policies mandating zero tolerance and family separation.) Today I look at two picture books and a graphic novel full of wise, loving insights into the problems and joys of immigrant generations within families. While these three recent works are about Vietnamese and Thai immigrants to the United States, their sharp observations extend beyond any one ethnicity or particular national borders.  Drawn Together (2018), written by Minh Le and illustrated by award-winning Dan Santat, is a gorgeous, heart-warming picture book. Vietnamese-American Le and Thai-American Santat call upon their own experiences of being unable to converse with grandparents who did not speak English to spotlight how communication between generations may occur in other ways. The loving grandfather in this book may not be able to offer school advice, but he and his elementary-aged grandson do come to a profound understanding. They bridge their language gap through making art—a resolution capsulized in what we finally realize is this book’s punning title.

Drawn Together (2018), written by Minh Le and illustrated by award-winning Dan Santat, is a gorgeous, heart-warming picture book. Vietnamese-American Le and Thai-American Santat call upon their own experiences of being unable to converse with grandparents who did not speak English to spotlight how communication between generations may occur in other ways. The loving grandfather in this book may not be able to offer school advice, but he and his elementary-aged grandson do come to a profound understanding. They bridge their language gap through making art—a resolution capsulized in what we finally realize is this book’s punning title. world beyond words” where they metaphorically “see each other for the first time.” The boy draws himself as a colorful wizard while the grandfather inks himself as a traditional Thai warrior as they joyfully depict themselves together battling and defeating a fierce dragon. Santat then shows them racing across a bridge towards one another, each assuming the previous colors of the other, as they next realize—“happily . . SPEECHLESS” in a smiling hug—that words no longer need be a barrier to communication. (Le’s cunning word play is again evident, with “speechless” now used in its positive sense.)

world beyond words” where they metaphorically “see each other for the first time.” The boy draws himself as a colorful wizard while the grandfather inks himself as a traditional Thai warrior as they joyfully depict themselves together battling and defeating a fierce dragon. Santat then shows them racing across a bridge towards one another, each assuming the previous colors of the other, as they next realize—“happily . . SPEECHLESS” in a smiling hug—that words no longer need be a barrier to communication. (Le’s cunning word play is again evident, with “speechless” now used in its positive sense.)  that this was his first effort to depict his own culture and that he lavished time and effort in learning and using traditional ink-and-paintbrush techniques. Readers of all ages will appreciate the visual richness here, with those detailed black-and-white drawings complemented by kid-colorful block images, both styles merging to convey the book’s satisfying, sumptuous “messages” about family and art. A brief, kid-friendly

that this was his first effort to depict his own culture and that he lavished time and effort in learning and using traditional ink-and-paintbrush techniques. Readers of all ages will appreciate the visual richness here, with those detailed black-and-white drawings complemented by kid-colorful block images, both styles merging to convey the book’s satisfying, sumptuous “messages” about family and art. A brief, kid-friendly  Picture book A Different Pond (2017) has won multiple awards for its Vietnamese-American creators, author Bao Phi and illustrator Thi Bui. This quietly luminous, poignant work is semi-autobiographical, focusing on a typical event in Phi’s boyhood in 1980s Minneapolis (now my own hometown). Unlike the unquestioned affluence depicted in Drawn Together, where a large-screen TV and ample food and art supplies are shown, Phi’s immigrant family was working-class and hard-pressed for cash. The grandson in suburban Drawn Together is dropped off and picked up by his mother in a shiny car. Bao Phi’s mother, though, rides a bicycle to her multiple, inner city jobs. And the central event in A Different Pond is an early morning fishing trip Phi and his father take not for sport but for food. As his father explains in the book, “Everything in America costs a lot of money.” This is particularly true for immigrants with low-paying jobs, a situation familiar also to illustrator Bui. On the book’s frontispiece, she dedicates the book “For the working class. . . .” while author Phi writes that it is “For my family, and for refugees everywhere.”

Picture book A Different Pond (2017) has won multiple awards for its Vietnamese-American creators, author Bao Phi and illustrator Thi Bui. This quietly luminous, poignant work is semi-autobiographical, focusing on a typical event in Phi’s boyhood in 1980s Minneapolis (now my own hometown). Unlike the unquestioned affluence depicted in Drawn Together, where a large-screen TV and ample food and art supplies are shown, Phi’s immigrant family was working-class and hard-pressed for cash. The grandson in suburban Drawn Together is dropped off and picked up by his mother in a shiny car. Bao Phi’s mother, though, rides a bicycle to her multiple, inner city jobs. And the central event in A Different Pond is an early morning fishing trip Phi and his father take not for sport but for food. As his father explains in the book, “Everything in America costs a lot of money.” This is particularly true for immigrants with low-paying jobs, a situation familiar also to illustrator Bui. On the book’s frontispiece, she dedicates the book “For the working class. . . .” while author Phi writes that it is “For my family, and for refugees everywhere.”  Bao Phi’s cash-poor family is rich in other ways. His gentle father’s steadfast kindness yields a smile rather than anger when the boy cannot bear to hook a minnow for bait. Bao Phi instead is praised and feels proud for efforts he can contribute. Father and son talk together comfortably about fishing in Vietnam. Neighborhood acquaintances interact in friendly ways with the pair, and the hard-working parents unite at night over family dinners with all five kids. They tell stories as “Mom will ask about their homework. Dad will nod and smile. . . .” It does not matter that, as the adult Phi poetically recalls, “A kid in my school said that my dad’s English sounds like a thick, dirty river. Because to me his English sounds like gentle rain.” Education is regularly valued and supported in this close-knit immigrant family—throughout the year, as well as on those momentous opening days.

Bao Phi’s cash-poor family is rich in other ways. His gentle father’s steadfast kindness yields a smile rather than anger when the boy cannot bear to hook a minnow for bait. Bao Phi instead is praised and feels proud for efforts he can contribute. Father and son talk together comfortably about fishing in Vietnam. Neighborhood acquaintances interact in friendly ways with the pair, and the hard-working parents unite at night over family dinners with all five kids. They tell stories as “Mom will ask about their homework. Dad will nod and smile. . . .” It does not matter that, as the adult Phi poetically recalls, “A kid in my school said that my dad’s English sounds like a thick, dirty river. Because to me his English sounds like gentle rain.” Education is regularly valued and supported in this close-knit immigrant family—throughout the year, as well as on those momentous opening days.  been one-note cartoons. She uses warm yellows, reds, and oranges to show the warmth of family life inside the Bui family apartment. In an interview, Bui explains how she included typical Vietnamese refugee elements, such as fish sauce stored in an old jar and a no-frills grocery store calendar, to personalize the family’s minimally-furnished apartment. Such typical elements also adorn the book’s end papers. I myself especially like the book’s final page, which shows the sleeping boy, colored with the book’s indoor, golden tones, surrounded by the cool blues of the “faraway ponds” of the family’s shared dreams.

been one-note cartoons. She uses warm yellows, reds, and oranges to show the warmth of family life inside the Bui family apartment. In an interview, Bui explains how she included typical Vietnamese refugee elements, such as fish sauce stored in an old jar and a no-frills grocery store calendar, to personalize the family’s minimally-furnished apartment. Such typical elements also adorn the book’s end papers. I myself especially like the book’s final page, which shows the sleeping boy, colored with the book’s indoor, golden tones, surrounded by the cool blues of the “faraway ponds” of the family’s shared dreams.  Thi Bui is both author and illustrator of her remarkable graphic family history, The Best We Could Do: An Illustrated Memoir (2017). Nominated for multiple national awards, this moving saga of the Bui family’s escape from war-torn Vietnam in the 1970s and their life in the U.S. will be appreciated by readers teen and older. Its framework of the adult Bui’s birthing and parenting her first child, together with the politics and mention of wartime violence, make this saga less engaging for tweens. Its life lessons—communicated in black, white, and subtle gradations of orange—are complex and sometime sad ones.

Thi Bui is both author and illustrator of her remarkable graphic family history, The Best We Could Do: An Illustrated Memoir (2017). Nominated for multiple national awards, this moving saga of the Bui family’s escape from war-torn Vietnam in the 1970s and their life in the U.S. will be appreciated by readers teen and older. Its framework of the adult Bui’s birthing and parenting her first child, together with the politics and mention of wartime violence, make this saga less engaging for tweens. Its life lessons—communicated in black, white, and subtle gradations of orange—are complex and sometime sad ones.  Unlike the contented son in A Different Pond, Thi as a girl dreamed about escaping her life. Generations of family violence and abandonment had shaped her father into a bitter man. Her mother’s personal goals had been set aside to meet their growing family’s needs in wartime. As the war escalated, their background as teachers endangered the pair rather than helping them in what is in now North Vietnam. Father Bui’s strengths combined with those of Thi’s mother enabled them to flee Vietnam and survive as refugees, but they paid a high price. Among other losses, their degrees were useless in the U.S., and the pair took on multiple minimum-wage jobs.

Unlike the contented son in A Different Pond, Thi as a girl dreamed about escaping her life. Generations of family violence and abandonment had shaped her father into a bitter man. Her mother’s personal goals had been set aside to meet their growing family’s needs in wartime. As the war escalated, their background as teachers endangered the pair rather than helping them in what is in now North Vietnam. Father Bui’s strengths combined with those of Thi’s mother enabled them to flee Vietnam and survive as refugees, but they paid a high price. Among other losses, their degrees were useless in the U.S., and the pair took on multiple minimum-wage jobs. intended lessons. The unintentional ones came from their un-exorcized demons. . . and from the habits they formed over so many years of trying to survive.” These words appear on a page alternating a large close-up of child Thi’s sad face with an image of her studying and then mid-distance views of her solemn parents, their separate, weary images in frames yoked together by a mysterious trail of smoke. Their children’s success in school is never enough to please these parents and calm their fears. Their harrowing experiences escaping Vietnam as “boat people” and then living in a refugee camp have left indelible psychological marks on them and, to a lesser extent, their children.