None of our family now remembers the actual grades that my adult son Daniel earned in fourth grade, but we all remember his early student activism. When the school principal decided that lunchroom noise was getting out of hand, she banned talking during lunchtime. Daniel then drew up a petition protesting that action but offering alternative ways to maintain order and allow talking. He got other students to sign the petition, leading the principal to lift her ban. That petition was also the beginning of Daniel’s ongoing involvement with communication and civic commitment, in his professional and personal life. As September begins a new school year here in Minnesota, our family’s experience reminds me that kids and teens learn a lot more in school than is ever measured on tests. There are multiple ways to “make the grade” in life, but sometimes formal education does not recognize this. Sometimes schools even hinder student progress or success. Today, I look at three graphic novels that deal with different types of “education” and miseducation, each with its own distinctive emotional register. One focuses on elementary school, while the others follow their protagonists into adulthood.

Comics Squad Recess (2014) is a compilation of eight rollicking “riffs” on elementary school life, each by a different comics author-illustrator or writer-and-artist pair. Its three editors—the sister and brother team of Jennifer L. Holm and Matthew Holm, along with Jarrett J. Kroscoczka—are themselves acclaimed graphic novelists. Their best-known characters—the Holms’ Babymouse and Kroscoczka’s Lunch Lady—are stars in their own separate series of popular, fun-filled graphic novels. In Comics Squad Recess, Baby Mouse and Lunch Lady not only anchor two of the eight stories but also appear as zestful narrators between the stories, urging the reader to turn the page, try out do-it-yourself projects, or buy zany imaginary products. These page-long “promos” are like the old-fashioned transitions that used to appear in comic books. Babymouse and Lunch Lady’s gleeful, pop-up appearances add to the fun as they connect the stories. The vivid two-color presentation here, alternating shades of orange with black and its gradations, is similarly attention-grabbing and cheerful.

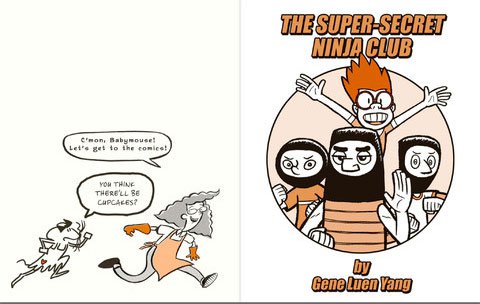

As its title suggests, most of the stories in Comics Squad Recess focus on the non-academic parts of school life: recess, winter vacation, lunch time, and hallway hijinks outside of class. How to interact with one another, be one’s own person, and discover the vast realms of the imagination are some of the serious topics explored in these funny tales of typical elementary school life. (There are also a couple of creative fantasy versions of school, with squirrels, cupcakes, and healthier snacks as characters.) I am hard-pressed to name a favorite story, but Gene Luen Yang’s “The Super-Secret Ninja Club” is lots of fun. Author-illustrator Yang often smartly lets readers piece together for ourselves how image and text fit together, as when someone outside the frame asks, “Anyone seen the star that’s supposed to go on top of the Christmas tree?” and we see a young, would-be ninja practicing “Throwing Weapons Techniques“ with the star as a make-shift shurikan. Providing the Japanese names for ninja practices is one way Yang, himself a teacher, slips still more knowledge into this tale—something that young-at-heart readers as well as kids will appreciate. (That active learning can take place outside of school—during winter break, or while holding a comics anthology in one’s hands—is just a given here.)

The one story that deals most directly with in-class, traditional ‘book learning’ will similarly appeal to a broad audience. Dav Pilkey’s “Book ‘Em, Dog Man,” purportedly a comic created by two elementary-school age students named George B. and Harold H., is prefaced by Pilkey’s clever letter from these boys’ first-grade teacher to their parents. She sternly recommends that they try to cure their sons of their “creative streak,” shown by the wild characters of the comic book they were told would not be acceptable homework. She cannot see past the spelling and grammar mistakes or the fantastic story line there to the imaginative, affectionate respect for reading in this kids’-eye view of a world bereft of readable books.

If your first thought, like mine, is that such a teacher’s response seems outdated, that most adults today recognize and respect how graphic literature reaches and moves kids, I will highlight this ironic fact: the most challenged book in schools and libraries in 2013 was Dav Pilkey’s popular comic book series Captain Underpants. This series featuring George B. and Harold H. as fourth graders was deemed offensive more often last year than E.L. James’ erotic bestseller Fifty Shades of Grey! Captain Underpants also topped the American Library Association’s 2012 list of ten most challenged books. Despite these bizarre facts, I am certain that readers of all ages will enjoy the verve and humor its creators bring to this Comics Squad Recess’ short book trailer . https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UiTRmUGRAeA

A different kind of school “failure” based on fact is revealed in Primates: The Fearless Science of Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Birute Galdikas (2013). This fictionalized biography, written by Jim Ottaviani and illustrated by Maris Wicks, shows how little relevance traditional education had to the scientific passions and success of these three groundbreaking naturalists. Their discoveries about surprising ways humans and other primates are alike and how primates act in the wild were self-motivated. We meet Jane Goodall as a preteen absorbed by Edgar Rice Burrough’s tales about Tarzan of the Apes. Watching farm animals had also piqued her curiosity about the natural world. Unable to afford college, clerical worker Goodall began her life’s study of chimpanzees after travelling to Africa and meeting paleontologist Louis Leakey, who supported her efforts. Dian Fossey, whose education and career as an occupational therapist did not satisfy her passionate interest in the great apes of Africa, was also aided by Leakey when the 31-year-old woman took a longed-for African vacation. On the other hand, Birute Galdikas was already an academic success in anthropology, when a lecture by Leakey and follow-up meeting with him changed her career path. With his help, she switched to the study of orangutans and their behavior. While Galdikas had to switch her academic focus, Goodall and Fossey had to “backtrack” and complete advanced college degrees in ethology in order, ironically, to receive official support and recognition of their considerable achievements. All three of these scientific pioneers had to combat the prevailing, mid-twentieth century prejudice that women were not intellectually suited to be scientists. In one more ironic twist, Louis Leakey’s own views on women’s innate differences from men—his belief that women are more patient and dedicated—spurred his support of these researchers.

Maris Wicks’ illustrations provide much of the gentle, sometimes rueful humor that dominates Primates. Against the vivid green hues of African and Malaysian jungles, she depicts human researchers stumbling awake; humans and apes attempting to outstare and out-sniff each other; and the awkward, sometimes physically irritating lessons humans have to learn about living in the wild. Wicks use of different typeface sizes, shapes, and colors to reflect wild sounds and noises is very effective, as are the frequent wordless panels which convey the stillness of these researchers observing primate life. Wicks even manages gently to underscore the unsuccessful ways in which Louis Leakey attempted to be more than “fatherly” with these female protégées. Every time he thinks about this, we see he has removed his spectacles, perhaps unconsciously, to appear more dashing. In one such scene, his wife and research partner Mary Leakey mutters to herself in the background, “Huh. Here we go again.” She is also happy to discover that Birute Galdikas is married, though readers later see the toll that a research career has on that relationship. The light ways in which these ‘adult’ matters are touched upon support author Ottaviani’s view that Primates is “designed to work well for [younger readers] but . . . it’s a book that appeals to anyone interested in primatology and the scientists who work in that field.” Treading that middle ground in readership may explain why Ottaviani omitted mention of Fossey’s unsolved murder, most likely by the animal poachers she opposed. Certainly, Ottaviani was more forthright about adult foibles and habits in his award-winning graphic biography, Feynman (2011), about physicist Richard Feynman, who had his own battles as a student and teacher with formal education. However, the more serious information about Fossey is readily discoverable in many resources, one being the Bibliography that Ottaviani provides in Primates.

The ways in which educational institutions fail to help and even harm such brilliant students is the subject of the graphic novel Genius (2013), written by Steven T. Seagle and illustrated by Teddy Kristiansen. These frequent collaborators here use muted pastels and sepia tones in a sincere, sometimes bleak, but ultimately hopeful story that twines the life of a fictional physicist with the experiences of 20th century luminary Albert Einstein. Seagle has said that he was inspired in part by the real-life experiences of his wife’s grandfather, a soldier during World War II who had met Einstein.

The book’s protagonist, Ted Halker, a pre-teen who ‘skips’ several grades in school, learns the hard way that there is a “chasm between knowledge . . . and knowing.” He is too physically different from other high school students to be readily accepted, and he lacks the social skills to change this. Ironically, his intellectual and social isolation in school, represented in a full page image that blocks him off centrally from other seated classmates, reoccurs when Halkner nears forty, having failed in the last decade to make the scientific leaps that characterized his early 20s. Once again, illustrator Kristiansen shows Halker center page, this time in a think tank’s block of cubicles, peopled now by younger scientists who are ahead of him intellectually. Einstein too achieved his greatest breakthroughs in theoretical physics in his 20s. But Einstein did not face losing his job, as Halker does, unless . . . just possibly, his aged father-in-law really did learn one of Einstein’s secrets while he served as one of the genius’ most trusted army guards. If so, perhaps Halker can use this information to help himself and his family. His wife, just diagnosed with cancer, needs expensive medical care, and his smart-aleck teenage son and gifted daughter are facing their own social and academic challenges.

Einstein’s supposed thoughts float through this book, as Halkner hears something from his father-in-law, represented in several wordless pages of dramatically more vivid, abstract patterns, overwhelmed finally by one dark color mysteriously covering an entire page. Is the old man’s whispered message a discovery about the theoretical anomaly Einstein himself seemed never able to resolve? Perhaps. But these pages may also represent the life-altering shift in viewpoint that Halkner soon makes, placing his family first and discovering a new, satisfying career as a high school physics teacher. He now knows he will be happy to be there for “that kid—or kids” who as geniuses need the kinds of help he did not receive in school. Grading student homework, including a notebook containing a doodled Einstein figure, Halkner is in this novel’s final panels content in new, hopeful ways. He no longer judges himself by the artificial standards and numbers that dominated his school-centric childhood and adolescence.

At the start of a new academic year, many students and schools face problems not addressed in this post: poverty, racism, physical and emotional deficits . . . overcrowding, understaffing and underfunding, government restrictions or requirements. I do realize the family anecdote which began this post shows just how fortunate and privileged we have been in our dealings with professional educators and schools. But what then of my adult son? I think he has finally forgiven us for not permitting him to skip grades in school. And I know he continues to “make the grade” in interesting, unusual ways. His former principal, now a family friend, was smiling as she recently told me she had received another written communication from Daniel—this time an e-mail suggesting sights to see when she toured Istanbul, his former home for several years. He had also mentioned places where one might enjoyably dine. I do not believe any of them were particularly quiet, even at lunch time.