November 1 . . . Is it too late now for a great Halloween-based book? Similarly, once this November’s national Native American Heritage Month is over, will it seem out-of-step to read about our country’s first peoples? And just how strictly should we limit this reading to peoples of the United States, when tribal identities sometimes cross its borders? Today I focus on two graphic works for teens that both celebrate and challenge the idea of books being “in season.” While holidays may provide dramatic focus for some books, the satisfaction and insights contained in the best of these works extend well beyond any celebrated days or months. Similarly, government borders do not negate the comparable experiences of native peoples in different countries. So, here are two books to savor and recommend throughout the year, within the U.S.A. and beyond.

November 1 . . . Is it too late now for a great Halloween-based book? Similarly, once this November’s national Native American Heritage Month is over, will it seem out-of-step to read about our country’s first peoples? And just how strictly should we limit this reading to peoples of the United States, when tribal identities sometimes cross its borders? Today I focus on two graphic works for teens that both celebrate and challenge the idea of books being “in season.” While holidays may provide dramatic focus for some books, the satisfaction and insights contained in the best of these works extend well beyond any celebrated days or months. Similarly, government borders do not negate the comparable experiences of native peoples in different countries. So, here are two books to savor and recommend throughout the year, within the U.S.A. and beyond.

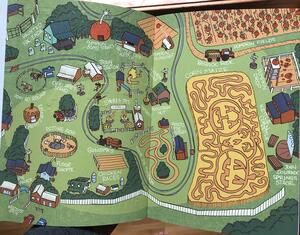

Pumpkinheads (2019) is a fun-packed, tenderhearted graphic novel about friendship and love, set during one last night at a yearly, elaborate “Pumpkin Patch and Autumn Festival.” Its extensive grounds—illustrated on the book’s interior covers—contain a maze, petting zoo, and rides as well as a variety of seasonal food huts and stands. The novel’s central characters, high school seniors Josiah and Deja, are patch co-workers finishing their fourth, final year as “seasonal best friends.” They will spend next year’s autumn at different colleges. What these characters reveal to us and learn about themselves form the warm, wise center of this book, given engaging life by its best-selling author Rainbow Rowell and award-winning illustrator Faith Erin Hicks. (I am heartened that none of these revelations centers on what once might have been noteworthy or controversial: interracial romance and bisexuality. These story elements are just matter-of-fact givens in Pumpkinheads.)

Pumpkinheads (2019) is a fun-packed, tenderhearted graphic novel about friendship and love, set during one last night at a yearly, elaborate “Pumpkin Patch and Autumn Festival.” Its extensive grounds—illustrated on the book’s interior covers—contain a maze, petting zoo, and rides as well as a variety of seasonal food huts and stands. The novel’s central characters, high school seniors Josiah and Deja, are patch co-workers finishing their fourth, final year as “seasonal best friends.” They will spend next year’s autumn at different colleges. What these characters reveal to us and learn about themselves form the warm, wise center of this book, given engaging life by its best-selling author Rainbow Rowell and award-winning illustrator Faith Erin Hicks. (I am heartened that none of these revelations centers on what once might have been noteworthy or controversial: interracial romance and bisexuality. These story elements are just matter-of-fact givens in Pumpkinheads.)

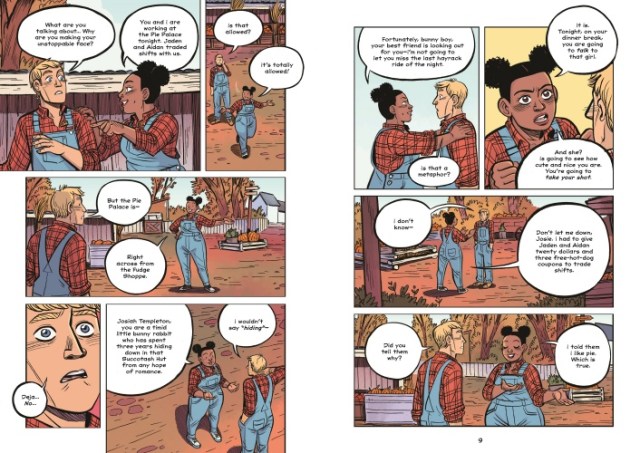

Rowell packs her story with the wordplay and crisp, character-specific dialogue her prose fans have come to expect. (I reviewed one of Rowell’s prose works here.) For instance, chapter headings and food stand names are typically puns, often referring to popular songs, films, or sayings. The pie stand asks visitors to “give piece a chance,” while another chapter is bittersweetly titled “S’More Problems.” Deja’s optimistic, outgoing personality is distinguished from hesitant, self-doubting Josiah’s through her many punning names for his long-time crush. He has never actually spoken to this girl, a fudge-shop worker, whom Deja teasingly calls “Super Fudge” and “Elmer Fudge,” also noting that “Girls just want to have Fudge.” Deja wants her shy friend to take this last chance to meet his “dream girl.” What happens while and after he attempts this becomes Pumpkinheads’ plot.

Rowell packs her story with the wordplay and crisp, character-specific dialogue her prose fans have come to expect. (I reviewed one of Rowell’s prose works here.) For instance, chapter headings and food stand names are typically puns, often referring to popular songs, films, or sayings. The pie stand asks visitors to “give piece a chance,” while another chapter is bittersweetly titled “S’More Problems.” Deja’s optimistic, outgoing personality is distinguished from hesitant, self-doubting Josiah’s through her many punning names for his long-time crush. He has never actually spoken to this girl, a fudge-shop worker, whom Deja teasingly calls “Super Fudge” and “Elmer Fudge,” also noting that “Girls just want to have Fudge.” Deja wants her shy friend to take this last chance to meet his “dream girl.” What happens while and after he attempts this becomes Pumpkinheads’ plot.

Rowell and Hicks make great, humorous use of the patch setting throughout this book. Josiah kindly calms a crying, frightened pre-schooler (whose sobbed “goooasteesses” probably refers to the zoo’s escaped goat rather than any costumed ghosts), while another youngster who early on snatches Deja’s caramel apple pops up throughout the evening. The times he appears as a background character, often unnoticed and not mentioned by Deja or Josiah, are just one way Hicks’ illustrations enrich Rowell’s storyline and characters.

At other points, wordless pages and sequences of wordless pages nimbly advance the story, often when speed is apt—such as racing away from that goat or towards the apple snatcher. The expressive faces of her cartoon-like drawings also wordlessly tell us how Deja and Josiah feel during some events. For example, Josiah has a perturbed expression when a youngster at the s’mores booth mocks Deja’s plumpness. Josiah grimly lets the boy’s marshmallow fall to the ground, while Deja watches, wide-eyed and appreciative. In interviews as well as in Pumpkinheads’ afterward, Rowell praises Hicks’ work, while Hicks herself says how much she appreciated the freedom she had to “do my own paneling and pacing” for this book.

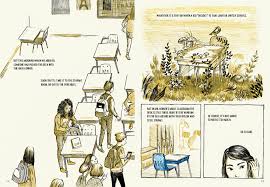

Varied paneling and pacing are hallmarks of graphic anthologies such as This Place: 150 Years Retold (2019), foreword by Alicia Elliot. This book has ten stories, created by twenty different indigenous authors and illustrators, which focus on significant people and events in the history of Canada’s first peoples. Even though most written histories have omitted or distorted these experiences, Elliot points out that oral history told within tribes and families has kept this information alive. Thus many more readers will now be introduced to the fierce determination of 19th century Annie Bannatyne, depicted with full color realism. In another story, a more limited color palette keyed to the “Red Clouds” of supernatural windigos conveys the family and tribal history of Fiddler

Varied paneling and pacing are hallmarks of graphic anthologies such as This Place: 150 Years Retold (2019), foreword by Alicia Elliot. This book has ten stories, created by twenty different indigenous authors and illustrators, which focus on significant people and events in the history of Canada’s first peoples. Even though most written histories have omitted or distorted these experiences, Elliot points out that oral history told within tribes and families has kept this information alive. Thus many more readers will now be introduced to the fierce determination of 19th century Annie Bannatyne, depicted with full color realism. In another story, a more limited color palette keyed to the “Red Clouds” of supernatural windigos conveys the family and tribal history of Fiddler  Jack. In “Nimkii,” which also features shamanism, a blue-green color palette communicates Inuit religion, with some panel-free pages and unrealistic juxtaposition of images being used dramatically to show the supernatural. A time-travel story initially set in the future, titled “Kitaskinaw 2350,” also omits some panels and uses non-realistic images to show its teen narrator’s first, shocked reactions to 21st century life. The future, we hopefully learn, provides native peoples with much better experiences.

Jack. In “Nimkii,” which also features shamanism, a blue-green color palette communicates Inuit religion, with some panel-free pages and unrealistic juxtaposition of images being used dramatically to show the supernatural. A time-travel story initially set in the future, titled “Kitaskinaw 2350,” also omits some panels and uses non-realistic images to show its teen narrator’s first, shocked reactions to 21st century life. The future, we hopefully learn, provides native peoples with much better experiences.

Young readers of this anthology may see or be shown the ways in which the experiences of U.S. tribes parallel  those of Canadian first peoples. Beyond broken governmental promises and pervasive social stereotyping, both countries have had long histories of harmfully separating youngsters from their families, ostensibly to help them acquire job skills and the country’s dominant language. This Space: 150 Years Retold will stir readers’ hearts as well as minds—a relevant, worthwhile, and interesting book to explore during this November’s national Native American Heritage month—as well as at other times too!

those of Canadian first peoples. Beyond broken governmental promises and pervasive social stereotyping, both countries have had long histories of harmfully separating youngsters from their families, ostensibly to help them acquire job skills and the country’s dominant language. This Space: 150 Years Retold will stir readers’ hearts as well as minds—a relevant, worthwhile, and interesting book to explore during this November’s national Native American Heritage month—as well as at other times too!

Other graphic works drawing upon indigenous culture and history include Moonshot: The Indigenous Comics Collection, volume 1 (2015) and volume 2 (2017). Both books contain tribe-specific stories ranging across North America and will engage tweens and teens. Enthusiastic readers of Pumpkinheads have a variety of follow-up choices. While Pumpkinheads is Rainbow Rowell’s first graphic novel, she has written issues of Marvel Comics monthly series Runaways, featuring super teen and tween-agers. There are currently four collected volumes of these (2018-2019), and I myself will now be taking a look at the first volume, Runaways: Find Your Way Home (2018).

Other graphic works drawing upon indigenous culture and history include Moonshot: The Indigenous Comics Collection, volume 1 (2015) and volume 2 (2017). Both books contain tribe-specific stories ranging across North America and will engage tweens and teens. Enthusiastic readers of Pumpkinheads have a variety of follow-up choices. While Pumpkinheads is Rainbow Rowell’s first graphic novel, she has written issues of Marvel Comics monthly series Runaways, featuring super teen and tween-agers. There are currently four collected volumes of these (2018-2019), and I myself will now be taking a look at the first volume, Runaways: Find Your Way Home (2018).

New fans of Canadian Faith Erin Hicks’ illustrations will appreciate her Eisner Award-winning collection of self-authored stories, The Adventures of Superhero Girl (2013; 2017, updated edition), which I reviewed here. The adventures of teen heroes in Hicks’ Nameless City trilogy (2016 – 2018) are also captivating and thought-provoking. I reviewed and recommended its first volume, titled simply The Nameless City (2016), when it was first published. Furthermore, Rowell and Hicks have said that they would be happy to work together again. While a novel-length sequel to Pumpkinheads is not probable, a short-story featuring Deja and Josiah remains a possibility!

New fans of Canadian Faith Erin Hicks’ illustrations will appreciate her Eisner Award-winning collection of self-authored stories, The Adventures of Superhero Girl (2013; 2017, updated edition), which I reviewed here. The adventures of teen heroes in Hicks’ Nameless City trilogy (2016 – 2018) are also captivating and thought-provoking. I reviewed and recommended its first volume, titled simply The Nameless City (2016), when it was first published. Furthermore, Rowell and Hicks have said that they would be happy to work together again. While a novel-length sequel to Pumpkinheads is not probable, a short-story featuring Deja and Josiah remains a possibility!

It takes guts to face one’s fears! But this effort is worthwhile . . . even if the results may take time.

It takes guts to face one’s fears! But this effort is worthwhile . . . even if the results may take time.  Guts begins wordlessly, with Telgemeier showing us how she and her mother suffered after they both caught younger daughter Amara’s stomach bug. Cartoonishly expressive eyes and green features in this full-color work convey the discomfort of their nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Boldly-lettered, vividly-colored sound effects accompany some of these scenes. Yet Raina comes to realize that the fear of puking or having diarrhea—her anxiety over this—is another sort of illness that she has acquired. Anxiety literally causes her pain as well as debilitating worry, affecting her actions at school as well as with friends. She is so afraid of catching another stomach bug! When medical tests all prove negative, the 5th grader at first wonders, “Can you be sick even if you are not sick? Can you be healthy even if you hurt?” Learning about anxiety, the symptoms it may cause, and how to deal with these situations becomes this book’s emphasis.

Guts begins wordlessly, with Telgemeier showing us how she and her mother suffered after they both caught younger daughter Amara’s stomach bug. Cartoonishly expressive eyes and green features in this full-color work convey the discomfort of their nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Boldly-lettered, vividly-colored sound effects accompany some of these scenes. Yet Raina comes to realize that the fear of puking or having diarrhea—her anxiety over this—is another sort of illness that she has acquired. Anxiety literally causes her pain as well as debilitating worry, affecting her actions at school as well as with friends. She is so afraid of catching another stomach bug! When medical tests all prove negative, the 5th grader at first wonders, “Can you be sick even if you are not sick? Can you be healthy even if you hurt?” Learning about anxiety, the symptoms it may cause, and how to deal with these situations becomes this book’s emphasis.  bombing of Japan, described in Barefoot Gen, a Japanese graphic novel,

bombing of Japan, described in Barefoot Gen, a Japanese graphic novel,  Wordless images again come to the forefront towards the conclusion of Guts, when Raina is handling stress more effectively, making new friends as well as retaining her oldest one. A joking—rather than worried—“FARRRRRT” in the memoir’s final sleep-over image captures Raina’s changed attitude. She now has a more comfortable, accepting and self-aware attitude towards her body and possible problems. She also realizes that other kids have their own worries, often akin to hers. As Telgemeier has her younger self say admiringly to a formerly disliked girl, “You’ve got guts.” A final Author’s Note helpfully updates readers with how the adult Telgemeier handles stress and her sensitive stomach.

Wordless images again come to the forefront towards the conclusion of Guts, when Raina is handling stress more effectively, making new friends as well as retaining her oldest one. A joking—rather than worried—“FARRRRRT” in the memoir’s final sleep-over image captures Raina’s changed attitude. She now has a more comfortable, accepting and self-aware attitude towards her body and possible problems. She also realizes that other kids have their own worries, often akin to hers. As Telgemeier has her younger self say admiringly to a formerly disliked girl, “You’ve got guts.” A final Author’s Note helpfully updates readers with how the adult Telgemeier handles stress and her sensitive stomach.  A new school year brings serious fun to students! Young athletes and mathletes, robotics teams and academic decathlon squads, science fair and history day entrants are just some of the young folks who gear up each year for fun. But competitions are just one outlet for serious play. Books complementing the curriculum offer all kinds of hijinks! Today I look at two graphic offerings that will tickle history buffs . . . and possibly create some new history fans, too. One is an ongoing series of funnily fantastic

A new school year brings serious fun to students! Young athletes and mathletes, robotics teams and academic decathlon squads, science fair and history day entrants are just some of the young folks who gear up each year for fun. But competitions are just one outlet for serious play. Books complementing the curriculum offer all kinds of hijinks! Today I look at two graphic offerings that will tickle history buffs . . . and possibly create some new history fans, too. One is an ongoing series of funnily fantastic  Neil Armstrong and Nat Love, Space Cowboys (2019) and Amelia Earhart and the Flying Chariot (2019) are recent additions to the “Time Twisters” series begun last year by author Steve Sheinkin and illustrated by Neil Swaab. These books join the duo’s Abraham Lincoln, Pro Wrestler (Time Twister #1, 2018) and Abigail Adams, Pirate of the Caribbean (Time Twister #2, 2018). The history mash-up “hook” here is obvious in the series label as well as each eye-popping individual title. These books are more than one-note jokes, though, as

Neil Armstrong and Nat Love, Space Cowboys (2019) and Amelia Earhart and the Flying Chariot (2019) are recent additions to the “Time Twisters” series begun last year by author Steve Sheinkin and illustrated by Neil Swaab. These books join the duo’s Abraham Lincoln, Pro Wrestler (Time Twister #1, 2018) and Abigail Adams, Pirate of the Caribbean (Time Twister #2, 2018). The history mash-up “hook” here is obvious in the series label as well as each eye-popping individual title. These books are more than one-note jokes, though, as  Though these books may be encountered out of sequence, readers will most enjoy them in order, since the series follows the ongoing adventures of 9-year old step-siblings Abby and Doc. At first, these 4th graders dislike what they and classmates call “boring history.” Yet in Abraham Lincoln, Pro Wrestler, several magical encounters with Lincoln before he becomes president begin to change their minds about history. His down-to-earth good humor and hokey jokes, along with Lincoln’s own desire for a dramatic change, surprise Abby and Doc almost as much as their discovery of a magical time portal—a large box containing just a few text books– in the school supply room.

Though these books may be encountered out of sequence, readers will most enjoy them in order, since the series follows the ongoing adventures of 9-year old step-siblings Abby and Doc. At first, these 4th graders dislike what they and classmates call “boring history.” Yet in Abraham Lincoln, Pro Wrestler, several magical encounters with Lincoln before he becomes president begin to change their minds about history. His down-to-earth good humor and hokey jokes, along with Lincoln’s own desire for a dramatic change, surprise Abby and Doc almost as much as their discovery of a magical time portal—a large box containing just a few text books– in the school supply room.  That box is a great metaphor for the factual details Sheinkin highlights to bring history to life. (Lincoln really did wrestle and tell jokes.) Swaab’s cartoon-like black and white drawings capture the energetic flailing of surprised characters as they tumble in and stumble out of the box, the first of the series’ unexpected time portals. Sheinkin’s pitch-perfect capture of school routines furthers the humor here. Of course, Lincoln’s lack of picture ID would deny him entry back into their school! Lincoln reappears in the series’ other books, acting as a kind of guardian as other historical figures fantastically take their own turns at escaping some of the best-known, often least enjoyable aspects of their lives.

That box is a great metaphor for the factual details Sheinkin highlights to bring history to life. (Lincoln really did wrestle and tell jokes.) Swaab’s cartoon-like black and white drawings capture the energetic flailing of surprised characters as they tumble in and stumble out of the box, the first of the series’ unexpected time portals. Sheinkin’s pitch-perfect capture of school routines furthers the humor here. Of course, Lincoln’s lack of picture ID would deny him entry back into their school! Lincoln reappears in the series’ other books, acting as a kind of guardian as other historical figures fantastically take their own turns at escaping some of the best-known, often least enjoyable aspects of their lives.  For instance, Abigail Adams resents the fact that—as one of our country’s earliest First Ladies—she is often most remembered for drying laundry inside the half-built White House. Sheinken foregrounds her strong interest in women’s and human rights by showing how she eagerly, temporarily becomes Abigail Adams, Pirate of the Caribbean. The loving, bickering relationship she shares with her president

For instance, Abigail Adams resents the fact that—as one of our country’s earliest First Ladies—she is often most remembered for drying laundry inside the half-built White House. Sheinken foregrounds her strong interest in women’s and human rights by showing how she eagerly, temporarily becomes Abigail Adams, Pirate of the Caribbean. The loving, bickering relationship she shares with her president  husband is central to the action-filled plot. He even learns to follow her ultimately famous advice to “Remember the Ladies.” This book, along with others in the series, concludes with author Sheinken separating sometimes surprising fact from fiction in an afterward titled “Un-Twisting History.”

husband is central to the action-filled plot. He even learns to follow her ultimately famous advice to “Remember the Ladies.” This book, along with others in the series, concludes with author Sheinken separating sometimes surprising fact from fiction in an afterward titled “Un-Twisting History.”  In the later books, Abby and Doc’s amazed classmates and teacher read along in their history text book as time-twists change events moment-to-moment. This technique is particularly engaging as Sheinkin and Swaab show how Nat Love, a famous 19th century Black cowboy, uses his lasso to rescue the first moon mission! By the end of Neil Armstrong and Nat Love, Space Cowboy, the once history-averse characters are asking for “MORE HISTORY!” The length of books in

In the later books, Abby and Doc’s amazed classmates and teacher read along in their history text book as time-twists change events moment-to-moment. This technique is particularly engaging as Sheinkin and Swaab show how Nat Love, a famous 19th century Black cowboy, uses his lasso to rescue the first moon mission! By the end of Neil Armstrong and Nat Love, Space Cowboy, the once history-averse characters are asking for “MORE HISTORY!” The length of books in  this series, each having 20 or so short chapters, is just right, including enough dramatic detail, character-driven dialogue, and humorous images to gain and hold our interest, too. Amelia Earhart and the Flying Chariot, which takes that historical figure along with Abby and Doc back to the earliest Olympic games, is similarly engaging. Swaab’s images and apt lettering of sound effects continue to detail the past while dramatizing time twists.

this series, each having 20 or so short chapters, is just right, including enough dramatic detail, character-driven dialogue, and humorous images to gain and hold our interest, too. Amelia Earhart and the Flying Chariot, which takes that historical figure along with Abby and Doc back to the earliest Olympic games, is similarly engaging. Swaab’s images and apt lettering of sound effects continue to detail the past while dramatizing time twists. Authentic, unusual (to us) details of 16th century British life are just one strength of the recently published Queen of the Sea (2019), written and illustrated majestically by

Authentic, unusual (to us) details of 16th century British life are just one strength of the recently published Queen of the Sea (2019), written and illustrated majestically by  Readers will care about Margaret, be fascinated by Eleanor, and connect to this distant time and place thanks to Meconis’ powerful storytelling. She creates a world here– complete with believable secondary characters, both loveable and hateful—with richly satisfying words and images, a combination of humor and adventures large and small. Queen of the Sea, I am sure, will win accolades as one of this year’s best tween/YA graphic novels.

Readers will care about Margaret, be fascinated by Eleanor, and connect to this distant time and place thanks to Meconis’ powerful storytelling. She creates a world here– complete with believable secondary characters, both loveable and hateful—with richly satisfying words and images, a combination of humor and adventures large and small. Queen of the Sea, I am sure, will win accolades as one of this year’s best tween/YA graphic novels. Meconis unifies her 400 page work by using the same format for Margaret’s detailed, often tongue-in-cheek understanding of topics ranging from kinds of nuns to canonical hours, convent sign language, and embroidery stitches. For each explanation, double-page spreads show circular items arranged concentrically. This technique also first introduces us to each nun and later reacquaints us with them once the surprised Margaret learns more about their past . . . and her own history. She was not just an infant who survived a shipwreck. Her

Meconis unifies her 400 page work by using the same format for Margaret’s detailed, often tongue-in-cheek understanding of topics ranging from kinds of nuns to canonical hours, convent sign language, and embroidery stitches. For each explanation, double-page spreads show circular items arranged concentrically. This technique also first introduces us to each nun and later reacquaints us with them once the surprised Margaret learns more about their past . . . and her own history. She was not just an infant who survived a shipwreck. Her  dramatic past, along with Queen Eleanor’s, and how that shapes their relationship is summed up in the chess games the two eventually play. As Eleanor remarks about the Queen pieces set up for their first game, “And now . . . they’re ready to fight.” Later, hidden rescues, a wild chase and a last-minute escape dominate the book’s final pages.

dramatic past, along with Queen Eleanor’s, and how that shapes their relationship is summed up in the chess games the two eventually play. As Eleanor remarks about the Queen pieces set up for their first game, “And now . . . they’re ready to fight.” Later, hidden rescues, a wild chase and a last-minute escape dominate the book’s final pages. language, reflecting what is being discussed or is occurring, also advance our understanding of the novel’s events. Alongside the central characters, servants, royal guards, nuns, and other island visitors—some expected, others not—brim with distinctive life. Readers may also delightedly note that whenever young Margaret is recounting her understanding of biblical events or folklore the style of drawing becomes simpler, the colors more vivid. This change is another layer of enjoyable sophistication in this many-layered, pleasurable historical graphic novel.

language, reflecting what is being discussed or is occurring, also advance our understanding of the novel’s events. Alongside the central characters, servants, royal guards, nuns, and other island visitors—some expected, others not—brim with distinctive life. Readers may also delightedly note that whenever young Margaret is recounting her understanding of biblical events or folklore the style of drawing becomes simpler, the colors more vivid. This change is another layer of enjoyable sophistication in this many-layered, pleasurable historical graphic novel. Similarly, fans of the Twisted History series might enjoy looking at some of author Steve Sheinkin’s other, earlier humorous takes on American history: King George—What Was His Problem: Everything your Schoolbooks Didn’t Tell You About the American Revolution (2008), Two Miserable Presidents: Everything Your Schoolbooks Didn’t Tell You About the Civil War (2008), and Which Way to the Wild West: Everything Your Schoolbooks Didn’t Tell You About

Similarly, fans of the Twisted History series might enjoy looking at some of author Steve Sheinkin’s other, earlier humorous takes on American history: King George—What Was His Problem: Everything your Schoolbooks Didn’t Tell You About the American Revolution (2008), Two Miserable Presidents: Everything Your Schoolbooks Didn’t Tell You About the Civil War (2008), and Which Way to the Wild West: Everything Your Schoolbooks Didn’t Tell You About  Westward Expansion (2008, 2015), all illustrated by Tim Robinson. Sheinkin himself illustrated as well as wrote funny graphic novel mash-ups of Western and Jewish immigrant history in three books about fictional Rabbi Harvey. These begin with The Adventures of Rabbi Harvey: A Graphic Novel of Jewish Wisdom and Wit in the Wild West (2006). I look forward to catching up with the other books in this series.

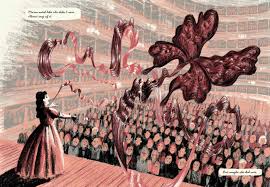

Westward Expansion (2008, 2015), all illustrated by Tim Robinson. Sheinkin himself illustrated as well as wrote funny graphic novel mash-ups of Western and Jewish immigrant history in three books about fictional Rabbi Harvey. These begin with The Adventures of Rabbi Harvey: A Graphic Novel of Jewish Wisdom and Wit in the Wild West (2006). I look forward to catching up with the other books in this series. Which song could be the soundtrack of your life today? This question is posed to the 8th grade characters in Operatic (2019), a wonderful new graphic novel combining music history and biography with smart insights into the complex tween and teenage years. Author Kyo Maclear and illustrator Byron Eggenschwiler do a pitch-perfect job showing us how the students in “Mr. K’s” music class respond to this assigned question, based on their evolving self-awareness, middle school dynamics, and new as well as long-standing friendships. This Canadian duo seamlessly blends their considerable talents in this richly satisfying work, which will move readers young and old with its poignancy as well as humor.

Which song could be the soundtrack of your life today? This question is posed to the 8th grade characters in Operatic (2019), a wonderful new graphic novel combining music history and biography with smart insights into the complex tween and teenage years. Author Kyo Maclear and illustrator Byron Eggenschwiler do a pitch-perfect job showing us how the students in “Mr. K’s” music class respond to this assigned question, based on their evolving self-awareness, middle school dynamics, and new as well as long-standing friendships. This Canadian duo seamlessly blends their considerable talents in this richly satisfying work, which will move readers young and old with its poignancy as well as humor.  As Maclear has

As Maclear has Maclear uses precise, apt words and verbal images to convey Charlie and Emile’s slow-growing affection for each other, along with the concern they share for Luka, absent now from school after homophobic bullying by some schoolmates. For instance, Charlie notes that Emile’s “voice lights up my belly like sparklers/ little pops of brightness in my gut.” When she thinks about Luka’s initial self-assurance, Charlie realizes that Luka “was kind of stubborn. Like the oak tree by the old tennis courts. That just keeps growing and doesn’t care that it’s not meant to be there. Like that.” Such word craft, including natural speech rhythms for all the book’s characters, has won MacClear awards for works written for

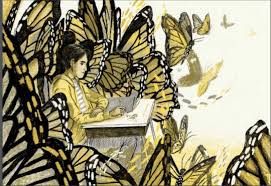

Maclear uses precise, apt words and verbal images to convey Charlie and Emile’s slow-growing affection for each other, along with the concern they share for Luka, absent now from school after homophobic bullying by some schoolmates. For instance, Charlie notes that Emile’s “voice lights up my belly like sparklers/ little pops of brightness in my gut.” When she thinks about Luka’s initial self-assurance, Charlie realizes that Luka “was kind of stubborn. Like the oak tree by the old tennis courts. That just keeps growing and doesn’t care that it’s not meant to be there. Like that.” Such word craft, including natural speech rhythms for all the book’s characters, has won MacClear awards for works written for  Eggenschwiler effectively uses color to code each character’s strand within the novel’s limited, muted palette: Charlie’s sections are golden yellow; Emile’s are dark grey; Luka’s parts are sky blue; and Maria Callas’ arc is rose red. When their stories overlap, either within the book’s main narrative or within a character’s imagination, so do the colors. For

Eggenschwiler effectively uses color to code each character’s strand within the novel’s limited, muted palette: Charlie’s sections are golden yellow; Emile’s are dark grey; Luka’s parts are sky blue; and Maria Callas’ arc is rose red. When their stories overlap, either within the book’s main narrative or within a character’s imagination, so do the colors. For  instance, the mystery behind Luka’s prolonged school absence, ultimately resolved well, is signaled by a jarringly blue desk. And when Charlie daydreams about Emile, who studies insects, she mentally pictures him reclining in a lush grotto composed of outsized, yellow and dark grey butterflies. This two page spread is just one instance of full or double page images where size conveys dramatic emphasis. The transporting impact of Maria Callas’ rich voice is seen in several red-hued full or double page images.

instance, the mystery behind Luka’s prolonged school absence, ultimately resolved well, is signaled by a jarringly blue desk. And when Charlie daydreams about Emile, who studies insects, she mentally pictures him reclining in a lush grotto composed of outsized, yellow and dark grey butterflies. This two page spread is just one instance of full or double page images where size conveys dramatic emphasis. The transporting impact of Maria Callas’ rich voice is seen in several red-hued full or double page images. Eggenschwiler also takes full advantage of narrative space to both advance and enhance Operatic’s story. Often, he deploys wordless panels or pages for this purpose. For instance, after Charlie’s mentally musing at the bottom of one page that Emile “has a way of looking sideways into my eyes that makes me feel kind of. . . ,“ we turn the page to see Charlie wordlessly melting into a puddle next to her classroom desk! This gently humorous image is a wonderful conclusion to that half-finished verbal thought. Similarly, when the young, unhappy Maria Callas borrows phonograph music records from her public library, we turn the page to see her eagerly, wordlessly examining her newest treasure even as she descends the library portico’s steps.

Eggenschwiler also takes full advantage of narrative space to both advance and enhance Operatic’s story. Often, he deploys wordless panels or pages for this purpose. For instance, after Charlie’s mentally musing at the bottom of one page that Emile “has a way of looking sideways into my eyes that makes me feel kind of. . . ,“ we turn the page to see Charlie wordlessly melting into a puddle next to her classroom desk! This gently humorous image is a wonderful conclusion to that half-finished verbal thought. Similarly, when the young, unhappy Maria Callas borrows phonograph music records from her public library, we turn the page to see her eagerly, wordlessly examining her newest treasure even as she descends the library portico’s steps.  Montage images, often employing hand-lettered words whose size and style—jittery and jagged to round and smooth—reflect different musical styles and volume, are other elements in Eggenschwiler’s visual repertoire here. In an interview, he explains that he first hand-draws these cross-hatched images in pencil, later coloring them further on a computer. Sometimes, montage images surreally juxtapose other school figures or family members of the main characters. At other points, Eggenschwiler shifts perspective so that at apt moments in the story we see events or objects through Mr. K’s or young Maria Callas’ eyes. Again, I note with amazement that Operatic is also this artist’s first graphic novel. Typically, he works full-time as an editorial illustrator, with other more limited experience as a

Montage images, often employing hand-lettered words whose size and style—jittery and jagged to round and smooth—reflect different musical styles and volume, are other elements in Eggenschwiler’s visual repertoire here. In an interview, he explains that he first hand-draws these cross-hatched images in pencil, later coloring them further on a computer. Sometimes, montage images surreally juxtapose other school figures or family members of the main characters. At other points, Eggenschwiler shifts perspective so that at apt moments in the story we see events or objects through Mr. K’s or young Maria Callas’ eyes. Again, I note with amazement that Operatic is also this artist’s first graphic novel. Typically, he works full-time as an editorial illustrator, with other more limited experience as a  I believe readers of Operatic will come away—as I have—eager to read and see more work by its gifted creators. Possibly you or they may want to listen to recordings by Maria Callas, see a recent

I believe readers of Operatic will come away—as I have—eager to read and see more work by its gifted creators. Possibly you or they may want to listen to recordings by Maria Callas, see a recent  debuts nationwide. The entertaining

debuts nationwide. The entertaining  Anticipating or recalling those 4th of July fireworks? Colorful blasts have been part of “Independence Day” celebrations ever since the U.S. Declaration of Independence

Anticipating or recalling those 4th of July fireworks? Colorful blasts have been part of “Independence Day” celebrations ever since the U.S. Declaration of Independence  own chapter. “Intentional Communities” are ones where “groups of people [chose] to radically remake their social structures,” while “Micronations” describe “tiny nations” whose names few people will recognize. “Failed Utopias” are grand “experiment[s]” whose failures were equally big, while “Visionary Environments” are accounts of the physical changes individuals have made, creating “wonderful and bizarre places” to “make their visions reality.” The last chapter, “Strange Dreams,” describes some “plans . . . and schemes” for new nations that never took shape at all.

own chapter. “Intentional Communities” are ones where “groups of people [chose] to radically remake their social structures,” while “Micronations” describe “tiny nations” whose names few people will recognize. “Failed Utopias” are grand “experiment[s]” whose failures were equally big, while “Visionary Environments” are accounts of the physical changes individuals have made, creating “wonderful and bizarre places” to “make their visions reality.” The last chapter, “Strange Dreams,” describes some “plans . . . and schemes” for new nations that never took shape at all.  For instance, after reading about “Libertatia,” a 17th century intentional community on Madagascar where for 25 years pirates and freed slaves lived in equality and harmony, readers might well ask about other countries started by former slaves or other ways some pirates rebelled against convention. There are a wealth of possible topics to pursue here during long summer days! Similarly, the section about “Oneida,” the failed 19th century utopia in upstate New York that became a hugely successful silverware company, might inspire readers to look into other utopian communities or the origins of popular or local businesses.

For instance, after reading about “Libertatia,” a 17th century intentional community on Madagascar where for 25 years pirates and freed slaves lived in equality and harmony, readers might well ask about other countries started by former slaves or other ways some pirates rebelled against convention. There are a wealth of possible topics to pursue here during long summer days! Similarly, the section about “Oneida,” the failed 19th century utopia in upstate New York that became a hugely successful silverware company, might inspire readers to look into other utopian communities or the origins of popular or local businesses.  Micronations such as “North Dumpling Island” near Connecticut have been founded by brilliant, wealthy eccentrics such as inventor Dean Kamen, while other micronations have been founded as tax dodges! Guilt and a father’s love inspired one visionary environment, the “Arizona Mystery Castle,” while razor blade tycoon King Camp Gillette’s strange dream of a New York city-state called “Metropolis” never took hold. (Millionaires do not automatically have political knowledge or even good sense—as many U.S. citizens today would attest.) Some new nations—such as “Auroville” in India—faded away after the death of an inspirational leader, while another Indian visionary’s plan, “Nek Chand’s Rock Garden,” survives today as a popular tourist attraction.

Micronations such as “North Dumpling Island” near Connecticut have been founded by brilliant, wealthy eccentrics such as inventor Dean Kamen, while other micronations have been founded as tax dodges! Guilt and a father’s love inspired one visionary environment, the “Arizona Mystery Castle,” while razor blade tycoon King Camp Gillette’s strange dream of a New York city-state called “Metropolis” never took hold. (Millionaires do not automatically have political knowledge or even good sense—as many U.S. citizens today would attest.) Some new nations—such as “Auroville” in India—faded away after the death of an inspirational leader, while another Indian visionary’s plan, “Nek Chand’s Rock Garden,” survives today as a popular tourist attraction. Sophie Dam’s illustrations support author Warner’ breezy tone in this book. Her cartoon-like line drawings and non-realistic color schemes are light-hearted, almost carnival-like, buoying up even the eventual failures or strange fates that befall most of the nations depicted here. Her playful treatment of panels—overlapping ones of different sizes, breaking through or omitting frames, and interjecting circular panels filled with characters congregating in surreal ways—is equally irreverent, as are some images here of traditional religious

Sophie Dam’s illustrations support author Warner’ breezy tone in this book. Her cartoon-like line drawings and non-realistic color schemes are light-hearted, almost carnival-like, buoying up even the eventual failures or strange fates that befall most of the nations depicted here. Her playful treatment of panels—overlapping ones of different sizes, breaking through or omitting frames, and interjecting circular panels filled with characters congregating in surreal ways—is equally irreverent, as are some images here of traditional religious  leaders and gay and lesbian nations. Some tween readers might have questions about those images and topics or about the book’s casual mention of other serious topics such as slavery. I wish the author or editor here had included a bibliography for further reading. While there are visual signposts—in the form of single or double splash pages—for each chapter and each new nation, there are no similar way signs for materials outside This Land is My Land. That omission is a failing.

leaders and gay and lesbian nations. Some tween readers might have questions about those images and topics or about the book’s casual mention of other serious topics such as slavery. I wish the author or editor here had included a bibliography for further reading. While there are visual signposts—in the form of single or double splash pages—for each chapter and each new nation, there are no similar way signs for materials outside This Land is My Land. That omission is a failing.  I was ready, site open and fingers poised, to purchase those “hot” on-line tickets, going on sale precisely at noon. One fumble and then . . . success! I had snagged our spots—tickets we would use exactly two months later, during our weeklong stay in Amsterdam. I felt like a Springsteen or Twins fan who had just won the Ticketmaster “‘lottery” for an upcoming, highly anticipated event. But the prized openings I had secured were to a Holocaust memorial—the

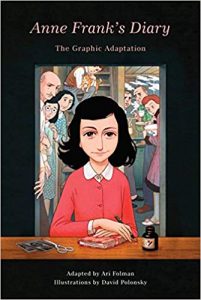

I was ready, site open and fingers poised, to purchase those “hot” on-line tickets, going on sale precisely at noon. One fumble and then . . . success! I had snagged our spots—tickets we would use exactly two months later, during our weeklong stay in Amsterdam. I felt like a Springsteen or Twins fan who had just won the Ticketmaster “‘lottery” for an upcoming, highly anticipated event. But the prized openings I had secured were to a Holocaust memorial—the  Visitors world-wide today flock to this building, since 1979 a museum commemorating that young victim of the Holocaust, made famous in the

Visitors world-wide today flock to this building, since 1979 a museum commemorating that young victim of the Holocaust, made famous in the  worked. The museum reproduces some of the décor of the Annex back then, but its rooms are empty of furniture. Visitors must imagine what life was like in those cramped quarters, drawing upon exhibits in other parts of the House. They tell much about the years between 1942 and 1944, when daring Dutch friends helped the endangered Jews hide, before the Nazis burst in on the morning of August 4, 1944. Visitors usually know that only Otto Frank survived the war to return to Amsterdam, after deportation and imprisonment in concentration camps. Dutch friends then gave him Anne’s diary and other family papers they had rescued and saved.

worked. The museum reproduces some of the décor of the Annex back then, but its rooms are empty of furniture. Visitors must imagine what life was like in those cramped quarters, drawing upon exhibits in other parts of the House. They tell much about the years between 1942 and 1944, when daring Dutch friends helped the endangered Jews hide, before the Nazis burst in on the morning of August 4, 1944. Visitors usually know that only Otto Frank survived the war to return to Amsterdam, after deportation and imprisonment in concentration camps. Dutch friends then gave him Anne’s diary and other family papers they had rescued and saved.  cover his eyes with one hand as his shoulders quaked with tears. As a film buff, I was particularly touched by the movie star items adorning one wall of Anne’s room. From her diary, we know how often she daydreamed about the photos she had put up there of such popular actors as Sonja Henie, Ginger Rogers, Robert Taylor and Robert Stack. This typical teenage enthusiasm is such a contrast to the circumscribed, terror-driven life Anne and the others led in the Secret Annex. I did not understand until recently, however, how Anne’s accessibility as a typical teen figures in the many controversies about her and her diary.

cover his eyes with one hand as his shoulders quaked with tears. As a film buff, I was particularly touched by the movie star items adorning one wall of Anne’s room. From her diary, we know how often she daydreamed about the photos she had put up there of such popular actors as Sonja Henie, Ginger Rogers, Robert Taylor and Robert Stack. This typical teenage enthusiasm is such a contrast to the circumscribed, terror-driven life Anne and the others led in the Secret Annex. I did not understand until recently, however, how Anne’s accessibility as a typical teen figures in the many controversies about her and her diary. until the 1990s appearance of several “Definitive” and “Critical” editions were these cuts restored. Those versions also explained that Anne had begun to revise her diary for possible publication, with this revision also covering several months absent from the original diary restored to Otto Frank. This month’s publication of Anne Frank: The Collected Works (2019) contains the different versions of the diary, along with short stories Anne wrote, and also contains for the first time five loose pages from the diary found after the Nazi raid. This history—along with fate of each Annex dweller—is on display at the museum. Yet there is much about the diary’s history that is not mentioned or only briefly touched upon there.

until the 1990s appearance of several “Definitive” and “Critical” editions were these cuts restored. Those versions also explained that Anne had begun to revise her diary for possible publication, with this revision also covering several months absent from the original diary restored to Otto Frank. This month’s publication of Anne Frank: The Collected Works (2019) contains the different versions of the diary, along with short stories Anne wrote, and also contains for the first time five loose pages from the diary found after the Nazi raid. This history—along with fate of each Annex dweller—is on display at the museum. Yet there is much about the diary’s history that is not mentioned or only briefly touched upon there. It is this play—by veteran playwrights Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett and first produced in 1955—which we know because it did become both a popular and critical success. Their Diary of Anne Frank won the Pulitzer Prize for best play and other major awards in 1956 and, decades later, won new kudos for revival productions. Goodrich and Hackett’s play was also the basis for the film, debuting in 1959, that won several Academy Awards. Levin, though, remained incensed at his work’s rejection. He sued Otto Frank and the successful play’s producers, claiming breach of contract and plagiarism of his writing. This suit was settled out of court, but Levin went on to write a

It is this play—by veteran playwrights Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett and first produced in 1955—which we know because it did become both a popular and critical success. Their Diary of Anne Frank won the Pulitzer Prize for best play and other major awards in 1956 and, decades later, won new kudos for revival productions. Goodrich and Hackett’s play was also the basis for the film, debuting in 1959, that won several Academy Awards. Levin, though, remained incensed at his work’s rejection. He sued Otto Frank and the successful play’s producers, claiming breach of contract and plagiarism of his writing. This suit was settled out of court, but Levin went on to write a  Primo Levi applaud the way Anne’s words, baring her soul, make the Holocaust real to people who cannot identify with the vast numbers of people actually slaughtered then. Others say that an ordinary girl unreasonably has been turned into an “icon” or saint, turning the Annex into a kind of pilgrimage “shrine.” Another criticism is that Anne’s youthful, upbeat responses have been spotlighted while her discouraged or bitter remarks have been overlooked. Many people recall the staged and filmed versions of Anne Frank saying, “I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart.” Far fewer know or remember that fifteen-year old Anne, after two discouraging years in the Secret Annex, also wrote “There’s a destructive urge in people, the urge to rage, murder, and kill.”

Primo Levi applaud the way Anne’s words, baring her soul, make the Holocaust real to people who cannot identify with the vast numbers of people actually slaughtered then. Others say that an ordinary girl unreasonably has been turned into an “icon” or saint, turning the Annex into a kind of pilgrimage “shrine.” Another criticism is that Anne’s youthful, upbeat responses have been spotlighted while her discouraged or bitter remarks have been overlooked. Many people recall the staged and filmed versions of Anne Frank saying, “I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart.” Far fewer know or remember that fifteen-year old Anne, after two discouraging years in the Secret Annex, also wrote “There’s a destructive urge in people, the urge to rage, murder, and kill.”  parts of the diary that mirror their own typical emotional “growing pains,” while other young readers have been inspired by Anne’s experiences to rethink their own roles and opportunities in life. For instance, Cara Weiss Wilson’s decades-long correspondence with Otto Frank, begun when she was a teen and later documented in

parts of the diary that mirror their own typical emotional “growing pains,” while other young readers have been inspired by Anne’s experiences to rethink their own roles and opportunities in life. For instance, Cara Weiss Wilson’s decades-long correspondence with Otto Frank, begun when she was a teen and later documented in  Opposing these fictions is a wealth of real life books by those who

Opposing these fictions is a wealth of real life books by those who  is fake. That outrageous claim is one despicable result of what has been an

is fake. That outrageous claim is one despicable result of what has been an

Anne Frank’s fame and conflicting images when he wrote and titled one of his complex short stories

Anne Frank’s fame and conflicting images when he wrote and titled one of his complex short stories They were the hardest sets of stairs to climb. Last month in Amsterdam, I visited the

They were the hardest sets of stairs to climb. Last month in Amsterdam, I visited the  Today I want to tell you how extraordinarily powerful and wise the latest graphic version of Anne’s diary is. It was initiated by the

Today I want to tell you how extraordinarily powerful and wise the latest graphic version of Anne’s diary is. It was initiated by the  as slaves working on a pyramid, resonate anew in light of Anne’s completed school project on ancient Egypt. Seeing the notebooks for that project in display cases also adds resonance to a double page spread capturing adult conflicts in the Annex. Mrs. Frank, Mrs. van Daan, and Mr. van Daan, arguing fiercely, are all shown as hissing sphinxes, twined round the words of their running disagreements. Sphinxes are among Anne’s drawings for her report. And, of course, seeing the surviving red-plaid diary itself adds immense emotional heft to the way she personalized her diary entries, writing them as letters to an imaginary best friend named “Kitty.”

as slaves working on a pyramid, resonate anew in light of Anne’s completed school project on ancient Egypt. Seeing the notebooks for that project in display cases also adds resonance to a double page spread capturing adult conflicts in the Annex. Mrs. Frank, Mrs. van Daan, and Mr. van Daan, arguing fiercely, are all shown as hissing sphinxes, twined round the words of their running disagreements. Sphinxes are among Anne’s drawings for her report. And, of course, seeing the surviving red-plaid diary itself adds immense emotional heft to the way she personalized her diary entries, writing them as letters to an imaginary best friend named “Kitty.”  Interposed with these serious moments are the angrily humorous thoughts teenaged Anne has about her ever-present companions. On one page, her noting their annoying repetition of the same complaints and concerns is emphasized by Polonsky’s drawing them satirically as wind-up toys. On another doublewide spread, their eating preoccupations are captured at dinner, with everyone shown as an animal whose typical gobbling or nibbling matches the person’ habits. In this adaptation, as in the diary Anne herself had begun t

Interposed with these serious moments are the angrily humorous thoughts teenaged Anne has about her ever-present companions. On one page, her noting their annoying repetition of the same complaints and concerns is emphasized by Polonsky’s drawing them satirically as wind-up toys. On another doublewide spread, their eating preoccupations are captured at dinner, with everyone shown as an animal whose typical gobbling or nibbling matches the person’ habits. In this adaptation, as in the diary Anne herself had begun t there before catching up with and following Anne during the next pain and terror-wracked months. I anticipate seeing Where is Anne Frank? with both high interest and dread. Drawing upon accounts from the handful of survivors already acquainted with the Franks, who saw Anne, Margot, and their mother during those post-capture months, this film is bound to be harrowing. I anticipate once more feeling as though I am walking in Anne Frank’s footsteps!

there before catching up with and following Anne during the next pain and terror-wracked months. I anticipate seeing Where is Anne Frank? with both high interest and dread. Drawing upon accounts from the handful of survivors already acquainted with the Franks, who saw Anne, Margot, and their mother during those post-capture months, this film is bound to be harrowing. I anticipate once more feeling as though I am walking in Anne Frank’s footsteps!  I do not know if the film will also shed light on the lingering question of how the Nazis learned about the Annex’s occupants. As I mentioned last fall while reviewing

I do not know if the film will also shed light on the lingering question of how the Nazis learned about the Annex’s occupants. As I mentioned last fall while reviewing  Private or public, some moments are seared into memory. I thought of this last month as images of Notre Dame blazed in the news. Its toppling spire also brought New York City’s falling Twin Towers to mind. Those images from 2001 had flared up recently as well, when President Trump perfidiously linked the devastating scenes to

Private or public, some moments are seared into memory. I thought of this last month as images of Notre Dame blazed in the news. Its toppling spire also brought New York City’s falling Twin Towers to mind. Those images from 2001 had flared up recently as well, when President Trump perfidiously linked the devastating scenes to  elders age and die—these are some of those personal memories which, however unique within our own lives, resonate as experiences others undergo as well. Today I look at two graphic works that illuminate these kinds of collective experience. One is a nearly-wordless graphic novel, probably best appreciated by readers tween and up, that could also enjoyably engage and promote discussion with some younger readers. The other is a stand-out addition to a recent

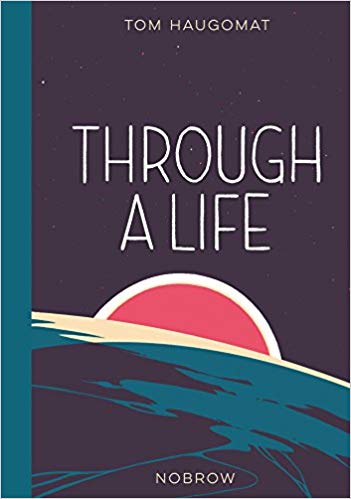

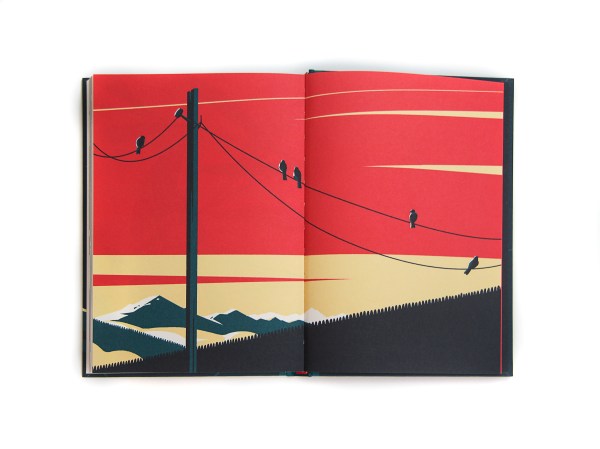

elders age and die—these are some of those personal memories which, however unique within our own lives, resonate as experiences others undergo as well. Today I look at two graphic works that illuminate these kinds of collective experience. One is a nearly-wordless graphic novel, probably best appreciated by readers tween and up, that could also enjoyably engage and promote discussion with some younger readers. The other is a stand-out addition to a recent  Through a Life (2018) uses bold images laced with subtle details to chart the birth through death experiences of its fictional main character. We see Rodney, born in 1955 Alaska, grow step-by-step to adulthood, becoming a NASA astronaut and later, after a failed marriage, returning to age in his childhood home. Nature in all its wonders is important throughout this character’s life. French author/illustrator Tom Haugomat’s decision to create this work within

Through a Life (2018) uses bold images laced with subtle details to chart the birth through death experiences of its fictional main character. We see Rodney, born in 1955 Alaska, grow step-by-step to adulthood, becoming a NASA astronaut and later, after a failed marriage, returning to age in his childhood home. Nature in all its wonders is important throughout this character’s life. French author/illustrator Tom Haugomat’s decision to create this work within  Color is the most obvious link throughout this evocative work, where the only words are place names and dates on the bottom of most left-side pages. These pinpoint places and times in Rodney’s life, beginning right before he is born. It takes a few pages before one realizes that the right-hand page in these pairs is what Rodney in the left-hand scene is himself viewing! Thus, we entertainingly get this child’s view through windows, a fence, a microscope, and even a mid-twentieth century View-Master toy. (In

Color is the most obvious link throughout this evocative work, where the only words are place names and dates on the bottom of most left-side pages. These pinpoint places and times in Rodney’s life, beginning right before he is born. It takes a few pages before one realizes that the right-hand page in these pairs is what Rodney in the left-hand scene is himself viewing! Thus, we entertainingly get this child’s view through windows, a fence, a microscope, and even a mid-twentieth century View-Master toy. (In  popular device.) Later, we observe what an adult Rodney views through TV screens, train windows, and computer screens, among other frames. Each view is shaped according to the situation it reflects—circular, oblong, square, and so on. The typicality of many events in Rodney’s life—the ways that they represent collective human moments—is enhanced by Haugomat’s omitting facial features in his stylized scenes.

popular device.) Later, we observe what an adult Rodney views through TV screens, train windows, and computer screens, among other frames. Each view is shaped according to the situation it reflects—circular, oblong, square, and so on. The typicality of many events in Rodney’s life—the ways that they represent collective human moments—is enhanced by Haugomat’s omitting facial features in his stylized scenes.  moments, centrally displayed on white pages, such highly-charged emotional or dramatic scenes are shown in full-page, double wide images, without worded dates or locations, in extended episodes covering six to twelve pages. In this way, Haugomat zooms into the church just before Rodney views his mother’s body; shows us how astronaut Rodney experiences being in outer space; depicts how Rodney as a NASA official observes (along with horrified spectators world-wide) the explosion of the Challenger shuttle craft; and, at the end of Rodney’s long life, even shows us how he perceives his final moments. The careful viewer will note poignant parallels between the scenes Rodney observes as a child and those that draw his attention in old age. These parallels, too, are often part of collective human experience.

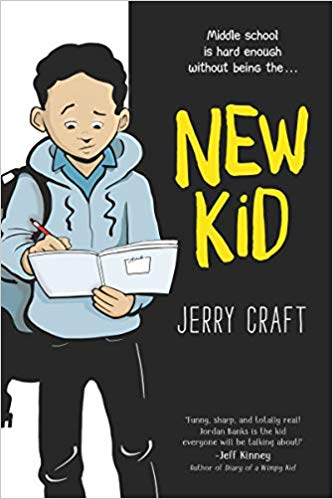

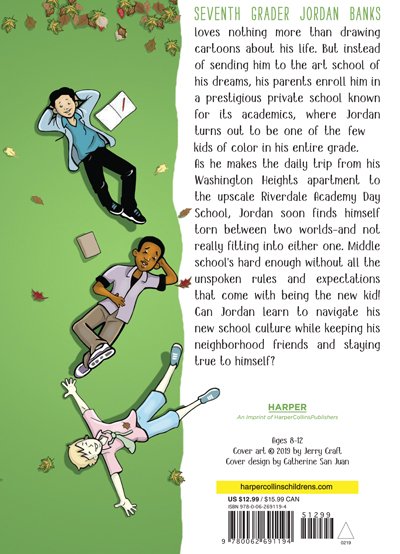

moments, centrally displayed on white pages, such highly-charged emotional or dramatic scenes are shown in full-page, double wide images, without worded dates or locations, in extended episodes covering six to twelve pages. In this way, Haugomat zooms into the church just before Rodney views his mother’s body; shows us how astronaut Rodney experiences being in outer space; depicts how Rodney as a NASA official observes (along with horrified spectators world-wide) the explosion of the Challenger shuttle craft; and, at the end of Rodney’s long life, even shows us how he perceives his final moments. The careful viewer will note poignant parallels between the scenes Rodney observes as a child and those that draw his attention in old age. These parallels, too, are often part of collective human experience. In New Kid (2019), lauded author/illustrator Jerry Craft also details collective experience while spotlighting the specific problems his central character, seventh grader Jordan Banks, faces in his new school. Many people experience awkwardness or uncertainty in new situations. As we learn mid-book here, even Jordan’s grandfather has to undergo being (and being called) the “new kid” at his Senior Center when he moves to a different neighborhood. Yet Jordan, a bright Black kid of modest means, has to cope with additional issues: the racial stereotypes about Blacks held by some teachers as well as students in that private, expensive, and primarily white school. His worried parents believe that cartoonist Jordan will gain more by using his scholarship there than he would from his first choice, an art school. Craft uses sharp insights and humor to depict Jordan’s first year at “Riverdale Academy.” In

In New Kid (2019), lauded author/illustrator Jerry Craft also details collective experience while spotlighting the specific problems his central character, seventh grader Jordan Banks, faces in his new school. Many people experience awkwardness or uncertainty in new situations. As we learn mid-book here, even Jordan’s grandfather has to undergo being (and being called) the “new kid” at his Senior Center when he moves to a different neighborhood. Yet Jordan, a bright Black kid of modest means, has to cope with additional issues: the racial stereotypes about Blacks held by some teachers as well as students in that private, expensive, and primarily white school. His worried parents believe that cartoonist Jordan will gain more by using his scholarship there than he would from his first choice, an art school. Craft uses sharp insights and humor to depict Jordan’s first year at “Riverdale Academy.” In  Jordan has concerned, well-educated parents, yet he and the few other Black students at Riverdale frequently face stereotyped assumptions that they come from single parent or indifferent homes, enmeshed in poverty or crime. Not every Black student there needs financial aid! Alternatively, some students and teachers thoughtlessly ignore the possibility that not everyone enrolled at Riverdale can afford to travel widely. Craft depicts these situations—along with the difficulties Jordan has in moving between his home neighborhood, friends there, and Riverdale classmates—through a seamless blend of words and images. These combine to give readers fully-fleshed, sympathetic characters.

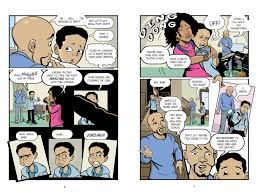

Jordan has concerned, well-educated parents, yet he and the few other Black students at Riverdale frequently face stereotyped assumptions that they come from single parent or indifferent homes, enmeshed in poverty or crime. Not every Black student there needs financial aid! Alternatively, some students and teachers thoughtlessly ignore the possibility that not everyone enrolled at Riverdale can afford to travel widely. Craft depicts these situations—along with the difficulties Jordan has in moving between his home neighborhood, friends there, and Riverdale classmates—through a seamless blend of words and images. These combine to give readers fully-fleshed, sympathetic characters. For instance, his home room teacher reveals her unthinking, implicit rejection of Black students as individuals by consistently misnaming them, substituting the similar–sounding names of other Black students. Jordan and Drew mock her bias (also taking some of the sting out of it) by coming up with ever-changing names for one another, all only having a “J” or and “D” in common. Jordan’s resentment only surfaces explicitly after this teacher without permission reads Jordan’s sketch book. His satirical cartoons there lead to a productive, if painful confrontation with her. Those black-and-white drawings are as visually distinct from Craft’s full-color main narrative as Jordan’s sketch-book comments are from his otherwise silent acceptance of Riverdale bias.

For instance, his home room teacher reveals her unthinking, implicit rejection of Black students as individuals by consistently misnaming them, substituting the similar–sounding names of other Black students. Jordan and Drew mock her bias (also taking some of the sting out of it) by coming up with ever-changing names for one another, all only having a “J” or and “D” in common. Jordan’s resentment only surfaces explicitly after this teacher without permission reads Jordan’s sketch book. His satirical cartoons there lead to a productive, if painful confrontation with her. Those black-and-white drawings are as visually distinct from Craft’s full-color main narrative as Jordan’s sketch-book comments are from his otherwise silent acceptance of Riverdale bias.  Sometimes his conflicted emotions are represented by small good and bad “angels” shown simultaneously whispering in his ears! Craft enhances fast-paced events here by frequently zooming in for close-ups, breaking or doing away with panel frames, and shifting perspectives, sometimes tilting images for added punch. The splash pages introducing the novel’s fourteen chapters zestily combine Craft’s skills as author/illustrator. Each chapter title and double-spread image is a pun on a popular movie or book, jokingly suggesting what is to come. For example, the chapter set in the school cafeteria is titled “The Hunger Games: Stop Mocking J.”

Sometimes his conflicted emotions are represented by small good and bad “angels” shown simultaneously whispering in his ears! Craft enhances fast-paced events here by frequently zooming in for close-ups, breaking or doing away with panel frames, and shifting perspectives, sometimes tilting images for added punch. The splash pages introducing the novel’s fourteen chapters zestily combine Craft’s skills as author/illustrator. Each chapter title and double-spread image is a pun on a popular movie or book, jokingly suggesting what is to come. For example, the chapter set in the school cafeteria is titled “The Hunger Games: Stop Mocking J.”  By the end of his first tumultuous year at Riverdale Academy, Jordan has grown successfully in all ways. His proud parents say “[Y]ou look like a new kid,” to which Jordan happily replies, “You know, I feel kinda like a new kid.” As Jerry Craft shows us, this character has learned that he can successfully speak out as well as fit in to more than one social situation. Cartoon hearts and smiling emojis dot the final images here of Jordan’s Riverdale School pals, while a rainbow and shining sun link them and Jordan to his home neighborhood friends, the kids he will see most in the upcoming summer.

By the end of his first tumultuous year at Riverdale Academy, Jordan has grown successfully in all ways. His proud parents say “[Y]ou look like a new kid,” to which Jordan happily replies, “You know, I feel kinda like a new kid.” As Jerry Craft shows us, this character has learned that he can successfully speak out as well as fit in to more than one social situation. Cartoon hearts and smiling emojis dot the final images here of Jordan’s Riverdale School pals, while a rainbow and shining sun link them and Jordan to his home neighborhood friends, the kids he will see most in the upcoming summer.  I was happy to learn that a sequel to New Kid will be published in Fall, 2020. This book’s many memorable moments have me looking ahead to that with my own smile in place. It is a feeling I believe readers will share—positive anticipation we need in uncertain times too often filled these days with

I was happy to learn that a sequel to New Kid will be published in Fall, 2020. This book’s many memorable moments have me looking ahead to that with my own smile in place. It is a feeling I believe readers will share—positive anticipation we need in uncertain times too often filled these days with  Every day—not just

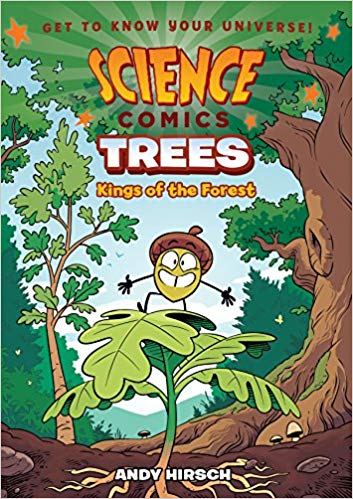

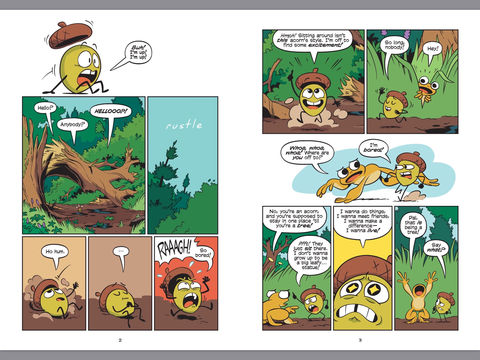

Every day—not just  Tweens and upper elementary school kids will enjoy the entertaining characters created by author/illustrator Andy Hirsch in Trees: Kings of the Forest (2018). His main character is a child-like acorn who mistakenly thinks that “grown-up” trees lead boring, limited lives. A series of new friends—ranging from a frog to a fungus, a leaf shoot to a beetle, then a spider, squirrel, bee and woodpecker—explain how wrong the acorn is, even as they teasingly bicker with one another.

Tweens and upper elementary school kids will enjoy the entertaining characters created by author/illustrator Andy Hirsch in Trees: Kings of the Forest (2018). His main character is a child-like acorn who mistakenly thinks that “grown-up” trees lead boring, limited lives. A series of new friends—ranging from a frog to a fungus, a leaf shoot to a beetle, then a spider, squirrel, bee and woodpecker—explain how wrong the acorn is, even as they teasingly bicker with one another.  some of the visual techniques that enhance humor here and move the action along smartly. I particularly liked the double spread, multi-character illustrations Hirsch created to depict forest ecosystems, fruit-bearing trees around the globe, and the photosynthesis cycle. Along with its engaging characters, the book’s final glossary and leaf illustrations offset its many bold-faced scientific terms for scientific processes. These at times are spelled out laboriously. This level of detail will benefit some readers even as it may annoy less-interested or younger ones.

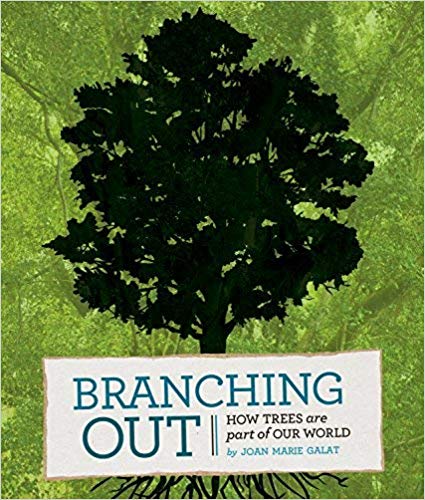

some of the visual techniques that enhance humor here and move the action along smartly. I particularly liked the double spread, multi-character illustrations Hirsch created to depict forest ecosystems, fruit-bearing trees around the globe, and the photosynthesis cycle. Along with its engaging characters, the book’s final glossary and leaf illustrations offset its many bold-faced scientific terms for scientific processes. These at times are spelled out laboriously. This level of detail will benefit some readers even as it may annoy less-interested or younger ones. Two books organized as catalogs of trees world-wide are a good choice for teen and tween readers. One is Branching Out: How Trees are part of Our World (2014), written by Canadian Joan Marie Galat and illustrated with high-grade, full color photographs. Besides examining eleven different tree species, award-winning Galat in this 64 page, clearly-written volume looks briefly at climate change, tree physiology, a forest ecosystem, and ways to save trees. Galat’s book is a crisp, well-done scientific overview of the endangered trees of planet Earth. Another catalog of trees world-wide is a wonderful complement to Branching Out, as it tackles this subject from a different perspective.

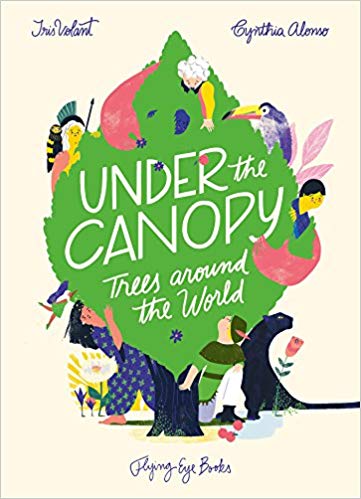

Two books organized as catalogs of trees world-wide are a good choice for teen and tween readers. One is Branching Out: How Trees are part of Our World (2014), written by Canadian Joan Marie Galat and illustrated with high-grade, full color photographs. Besides examining eleven different tree species, award-winning Galat in this 64 page, clearly-written volume looks briefly at climate change, tree physiology, a forest ecosystem, and ways to save trees. Galat’s book is a crisp, well-done scientific overview of the endangered trees of planet Earth. Another catalog of trees world-wide is a wonderful complement to Branching Out, as it tackles this subject from a different perspective.  Under the Canopy: Trees Around the World (2018) is a beautiful, oversized picture book, focusing on the myths and legends about seventeen tree species and four forests around the globe. Argentinian illustrator Cynthia Alonso’s luminous, saturated, and imaginatively stylized images will keep readers looking at and revisiting each double spread section. Alonso emphasizes the stories retold here by author “Iris Volant,” a pen name for Flying Eye Press’ author/editor Harriet Birkenshaw. The final double spread illustrating the seventeen different species may lead readers back to more science-oriented texts about these trees, only briefly identified here in their individual sections. Of course, readers of all ages can take pleasure in this lushly-rendered and designed picture book.

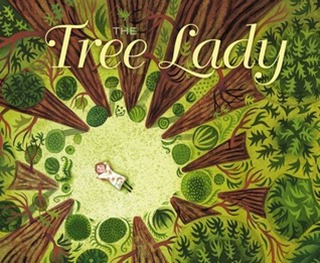

Under the Canopy: Trees Around the World (2018) is a beautiful, oversized picture book, focusing on the myths and legends about seventeen tree species and four forests around the globe. Argentinian illustrator Cynthia Alonso’s luminous, saturated, and imaginatively stylized images will keep readers looking at and revisiting each double spread section. Alonso emphasizes the stories retold here by author “Iris Volant,” a pen name for Flying Eye Press’ author/editor Harriet Birkenshaw. The final double spread illustrating the seventeen different species may lead readers back to more science-oriented texts about these trees, only briefly identified here in their individual sections. Of course, readers of all ages can take pleasure in this lushly-rendered and designed picture book.  The wide-ranging appeal of picture books is why I also want to spotlight some tree-related picture book biographies. The Tree Lady: How One Tree-Loving Woman Changed a City Forever (2013; 2018), written by H. Joseph Hopkins and illustrated by Jill McElmurry, depicts the impact determined “Kate” Sessions (1857 to 1940) had on the landscape of her adopted city, San Diego, California. This book’s vertiginous cover is as boldly designed as Sessions’ successful plans were for planting and tending a global variety of trees. She was inspired by her girlhood love of trees and the scientific education it led her to obtain. McElmurry uses gouache for the stylized American

The wide-ranging appeal of picture books is why I also want to spotlight some tree-related picture book biographies. The Tree Lady: How One Tree-Loving Woman Changed a City Forever (2013; 2018), written by H. Joseph Hopkins and illustrated by Jill McElmurry, depicts the impact determined “Kate” Sessions (1857 to 1940) had on the landscape of her adopted city, San Diego, California. This book’s vertiginous cover is as boldly designed as Sessions’ successful plans were for planting and tending a global variety of trees. She was inspired by her girlhood love of trees and the scientific education it led her to obtain. McElmurry uses gouache for the stylized American  folk art figures and patterns illustrating Hopkins’ text, which emphasizes Sessions’ pioneering vision and determination. She had goals and dreams beyond any then deemed desirable or even achievable for women. No one believed these goals were possible, “[b]ut Kate did,” as Hopkins notes in this book’s effective refrain.