“Popularity” changes and is rarely “one-size-fits-all.” We could see such trending last month in back-to-school clothing sales and, more significantly, the toppling of Confederate monuments that lionized slavery’s defenders. Heroism is time and culture-sensitive. This is equally true of the superheroes who figure in many comics, past and present. Even well-known heroes may have their costumes and roles filled by very different people.

“Popularity” changes and is rarely “one-size-fits-all.” We could see such trending last month in back-to-school clothing sales and, more significantly, the toppling of Confederate monuments that lionized slavery’s defenders. Heroism is time and culture-sensitive. This is equally true of the superheroes who figure in many comics, past and present. Even well-known heroes may have their costumes and roles filled by very different people.

In past posts, I have discussed the comic book adventures of a Black Captain America; a Pakistani-American, Muslim Miss Marvel; and a Hispanic Spiderman. These incarnations of iconic heroes of course battle evil, but their cultural diversity has them facing some challenges that never confronted the original white wearers of their costumes. These diverse heroes will never be popular with the KKK, but they have been a hit with a much wider audience. (Yet is the popularity of an icon’s new holder always reliable? Donald Trump, now occupying the iconic position of U.S. president, is still trending well with many people who voted for him, but. . . .)

In past posts, I have discussed the comic book adventures of a Black Captain America; a Pakistani-American, Muslim Miss Marvel; and a Hispanic Spiderman. These incarnations of iconic heroes of course battle evil, but their cultural diversity has them facing some challenges that never confronted the original white wearers of their costumes. These diverse heroes will never be popular with the KKK, but they have been a hit with a much wider audience. (Yet is the popularity of an icon’s new holder always reliable? Donald Trump, now occupying the iconic position of U.S. president, is still trending well with many people who voted for him, but. . . .)

Today I look at two fresh takes on traditional superheroes, one relatively little-known and the other a world-wide icon. The first, with its 4th grade main character, will have particular appeal for kids in this back-to-school month. Yet the Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur comic book series will also charm older readers sympathetic to tween-age woes. On the other hand, even though Superman comics are read by all ages, the characters and focus of offshoot graphic novel It’s a Bird . . . make it best suited to readers teen and older.

Today I look at two fresh takes on traditional superheroes, one relatively little-known and the other a world-wide icon. The first, with its 4th grade main character, will have particular appeal for kids in this back-to-school month. Yet the Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur comic book series will also charm older readers sympathetic to tween-age woes. On the other hand, even though Superman comics are read by all ages, the characters and focus of offshoot graphic novel It’s a Bird . . . make it best suited to readers teen and older.

The Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur comics (collected to date in three volumes, 2016-2017) revamp a late 1970s comic series featuring prehistoric heroes Moon Boy and Devil Dinosaur. (This “good guy” creature was named Devil due to its red hide, permanently scorched red in a fire it survived.) In the current series, set in the same comic book universe as Ms. Marvel, writers Brandon Montclare and Amy Reeder’s hero is nine year old Lunella Lafayette, a Black girl living with her parents on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Until a time warp brings Devil Dinosaur to 2016 New York, Lunella’s biggest problems have been dealing with school and parents. Lunella is genius-level smart and scientific, but her public-school classes bore her, getting her into trouble. Knowledgeable but sassy Lunella answers back in ways that can befuddle her science teacher. For instance, that well-meaning adult does not recognize the debunked scientific term “phlogiston” when Lunella snaps it out. Her parents’ worries and expectations frustrate Lunella to tears, even though she loves them. These problems intensify once Devil Dinosaur appears.

The Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur comics (collected to date in three volumes, 2016-2017) revamp a late 1970s comic series featuring prehistoric heroes Moon Boy and Devil Dinosaur. (This “good guy” creature was named Devil due to its red hide, permanently scorched red in a fire it survived.) In the current series, set in the same comic book universe as Ms. Marvel, writers Brandon Montclare and Amy Reeder’s hero is nine year old Lunella Lafayette, a Black girl living with her parents on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Until a time warp brings Devil Dinosaur to 2016 New York, Lunella’s biggest problems have been dealing with school and parents. Lunella is genius-level smart and scientific, but her public-school classes bore her, getting her into trouble. Knowledgeable but sassy Lunella answers back in ways that can befuddle her science teacher. For instance, that well-meaning adult does not recognize the debunked scientific term “phlogiston” when Lunella snaps it out. Her parents’ worries and expectations frustrate Lunella to tears, even though she loves them. These problems intensify once Devil Dinosaur appears.

Affected by the same alien gas that mutated Kamala Khan into Ms. Marvel, Lunella experiences a much less useful mutation. She has episodes of uncontrollable, temporary exchange of consciousness with Devil Dinosaur! These lead everyone to think that the girl genius is having mental breakdowns. This series’ delights include its spot-on depiction of school life, with sharp characterizations of Lunella’s classmates and teachers, including the newest student, another scientific whiz kid who is really an outer-space alien. Secretive “Marvin’s” rebellious relationship with his loving parents mirrors Lunella’s.

Affected by the same alien gas that mutated Kamala Khan into Ms. Marvel, Lunella experiences a much less useful mutation. She has episodes of uncontrollable, temporary exchange of consciousness with Devil Dinosaur! These lead everyone to think that the girl genius is having mental breakdowns. This series’ delights include its spot-on depiction of school life, with sharp characterizations of Lunella’s classmates and teachers, including the newest student, another scientific whiz kid who is really an outer-space alien. Secretive “Marvin’s” rebellious relationship with his loving parents mirrors Lunella’s.

Despite these increasing problems, Lunella does not retreat from challenges. She becomes crime-fighting Moon Girl (a name derived from a favorite t-shirt), using her smarts and scientific know-how in combination with Devil Dinosaur’s strength and size to battle assorted villains. Some of these foes are villains from other Marvel comics, just as some of Lunella’s allies are superheroes such as the Hulk and the Thing, as well as Ms. Marvel herself. Over the course of the three volumes, Lunella comes to realize the value of friends as well as allies, of fitting in as well as standing out in a crowd. Yet the authors also support her exceptionality and its relationship to scientific progress. Each chapter (originally a separate comic book issue) begins with an apt quotation from a real-life science high achiever, often a woman. One is geneticist Rosalind Franklin’s remark that “Science and everyday life cannot and should not be separated.”

Despite these increasing problems, Lunella does not retreat from challenges. She becomes crime-fighting Moon Girl (a name derived from a favorite t-shirt), using her smarts and scientific know-how in combination with Devil Dinosaur’s strength and size to battle assorted villains. Some of these foes are villains from other Marvel comics, just as some of Lunella’s allies are superheroes such as the Hulk and the Thing, as well as Ms. Marvel herself. Over the course of the three volumes, Lunella comes to realize the value of friends as well as allies, of fitting in as well as standing out in a crowd. Yet the authors also support her exceptionality and its relationship to scientific progress. Each chapter (originally a separate comic book issue) begins with an apt quotation from a real-life science high achiever, often a woman. One is geneticist Rosalind Franklin’s remark that “Science and everyday life cannot and should not be separated.”

Artists Natacha Bustos, Marco Failla, and Ray-Anthony Height—working with colorist Tamira Bonvillain and letterist Travis Lanham—advance plots and ideas here in effective, very enjoyable ways. From the details of science-loving Lunella’s room to inserted panels with close-ups of emotional faces, to panels drawn at differing angles to emphasize changes in height or spread across pages to emphasize action and motion—visual elements meld seamlessly with well-crafted text. Bright, bold colors suit Lunella’s personality as well as classroom interactions and the physical confrontations that occur more frequently than quiet moments for  Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur. Similarly, the sound effects that accompany Lunella’s perpetual race to get to school on time as well as her heroic battles are amplified by apt changes in font and color. The “TAP TAP TAP” of roller skates is shown differently than “DIIING” of the late bell and the “ROAR” of angry Devil Dinosaur. Lunella is such an engaging character—imperfect but growing, fierce in ambition but also in love and loyalty—that I am willing to overlook what felt like too many “guest appearances” by other superheroes in Volume 3. I look forward to Volume 4 of Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur’s collected adventures, scheduled for publication in January, 2018.

Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur. Similarly, the sound effects that accompany Lunella’s perpetual race to get to school on time as well as her heroic battles are amplified by apt changes in font and color. The “TAP TAP TAP” of roller skates is shown differently than “DIIING” of the late bell and the “ROAR” of angry Devil Dinosaur. Lunella is such an engaging character—imperfect but growing, fierce in ambition but also in love and loyalty—that I am willing to overlook what felt like too many “guest appearances” by other superheroes in Volume 3. I look forward to Volume 4 of Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur’s collected adventures, scheduled for publication in January, 2018.

Why do some superheroes, such as the original Devil Dinosaur, remain little-known while others, such as Superman, become icons? Author Steven T. Seagle tackles this question in It’s a Bird . . . (2004; 2010; 2017) which won artist Teddy Kristiansen an Eisner Award for best interior art in 2005, upon its first publication. (The pair has collaborated on other successful graphic novels, including Genius, which I reviewed here in 2014.) In this semi-autobiographical work, Seagle explores how personal as well as cultural reasons may influence popularity.

Why do some superheroes, such as the original Devil Dinosaur, remain little-known while others, such as Superman, become icons? Author Steven T. Seagle tackles this question in It’s a Bird . . . (2004; 2010; 2017) which won artist Teddy Kristiansen an Eisner Award for best interior art in 2005, upon its first publication. (The pair has collaborated on other successful graphic novels, including Genius, which I reviewed here in 2014.) In this semi-autobiographical work, Seagle explores how personal as well as cultural reasons may influence popularity.

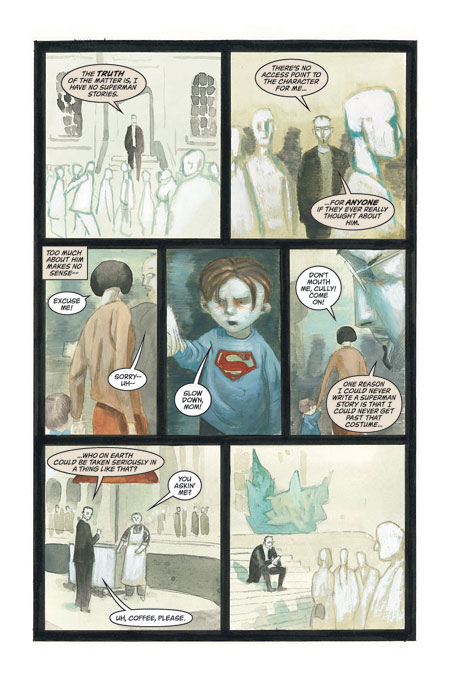

The narrator of It’s a Bird . . . , a comic book writer, is dismayed rather than thrilled when he is offered the rare chance to write Superman stories for its franchise owner, DC Comics. We slowly learn that he  associates this hero with the dreaded family secret he discovered as a five year old—the fact that Huntington’s Chorea, an incurable and fatal disease, runs in his family. He is wearing a Superman t-shirt and reading a Superman comic when he overhears a telling hospital conversation and glimpses the medical report about his grandmother, dying from this disease. In interviews, Seagle has spoken about his family’s Huntington’s disease, and he dedicated It’s a Bird to his Aunt Sarah, who “did not get to see it.” Along with letterer Todd Klein, artist Kristiansen does a masterful job of conveying these early experiences—half-read pages, stern adult faces and bewildered children drawn with child-like simplicity, in muted water colors. Only the comics image of Superman and a remembered, parallel “S” on the medical report are colored boldly. Later, we see that t-shirt “S” and tearful eyes also recalled in red.

associates this hero with the dreaded family secret he discovered as a five year old—the fact that Huntington’s Chorea, an incurable and fatal disease, runs in his family. He is wearing a Superman t-shirt and reading a Superman comic when he overhears a telling hospital conversation and glimpses the medical report about his grandmother, dying from this disease. In interviews, Seagle has spoken about his family’s Huntington’s disease, and he dedicated It’s a Bird to his Aunt Sarah, who “did not get to see it.” Along with letterer Todd Klein, artist Kristiansen does a masterful job of conveying these early experiences—half-read pages, stern adult faces and bewildered children drawn with child-like simplicity, in muted water colors. Only the comics image of Superman and a remembered, parallel “S” on the medical report are colored boldly. Later, we see that t-shirt “S” and tearful eyes also recalled in red.

A major portion of It’s a Bird . . . depicts how the narrator/Seagle comes to terms with his family’s genetic burden—the ways in which keeping silent about it and his fears have affected his personal relationships as well as the professional opportunity that now stymies him. As he tries to put off any final decision about writing Superman, we are shown each of the culturally-defined character traits of this iconic figure, and how these stack up in the real world.

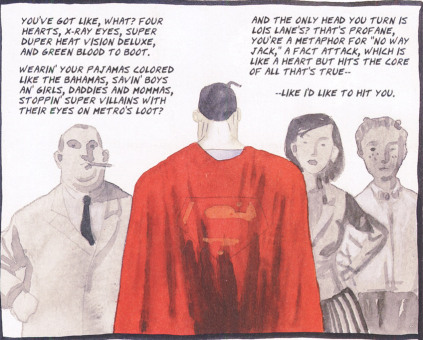

It’s a Bird . . . spotlights the ways in which many people in the U.S.A. are even greater “outsiders,” with their own “secret identities,” than the character of Superman is. The idea of an ubermench or “superman” has historical precedents which have been twisted to oppress rather than help. Also, in real life as well as this novel many people besides Superman have sought to create their own “fortress of solitude,” often with unfortunate results. Each of these and other iconic aspects of the Superman character is given its own several page sidebar, depicted in a separate, unifying color scheme and in a different, identifiable artistic style, ranging from Cubism to the four-color dots of old-fashioned comics. There are apt font changes, too. I especially like the entire page devoted to different versions of the letter “S,” and to the double spread about the “The Alien,” with full color and grey-tone images illustrating Seagle’s “rap” about all those treated as alien in 21st century America.

It’s a Bird . . . spotlights the ways in which many people in the U.S.A. are even greater “outsiders,” with their own “secret identities,” than the character of Superman is. The idea of an ubermench or “superman” has historical precedents which have been twisted to oppress rather than help. Also, in real life as well as this novel many people besides Superman have sought to create their own “fortress of solitude,” often with unfortunate results. Each of these and other iconic aspects of the Superman character is given its own several page sidebar, depicted in a separate, unifying color scheme and in a different, identifiable artistic style, ranging from Cubism to the four-color dots of old-fashioned comics. There are apt font changes, too. I especially like the entire page devoted to different versions of the letter “S,” and to the double spread about the “The Alien,” with full color and grey-tone images illustrating Seagle’s “rap” about all those treated as alien in 21st century America.

It’s a Bird . . . is itself just the kind of personalized take on Superman that its narrator finally decides to write, accepting the offered job. He decides to stay fully in the race that is life, to “turn the page and know what was going to happen next.” The final frames show this character telling two small boys, who resemble himself and his brother as kids, that what is up in the sky is neither a plane nor a bird but “Superman. . . . You can see him if you look close enough, but you really have to  want it.” Superman is both cultural icon and the personal favorite of the narrator’s immigrant taxi-driving friend because Rafa wants to believe in this figure, in the American dream. In his words, “Superman versus anyone? It’s Superman. America, baby, red, white, and blue.”

want it.” Superman is both cultural icon and the personal favorite of the narrator’s immigrant taxi-driving friend because Rafa wants to believe in this figure, in the American dream. In his words, “Superman versus anyone? It’s Superman. America, baby, red, white, and blue.”

These kinds of sophisticated insights into iconic popularity, along with emphasis on adult choices and many sidebars, are elements that direct this work towards older readers. Ironically, this narrative and visual richness would, I believe, not be a hit with the current resident of our own iconic White House. While I can easily see President Trump saying something to small children about Superman (after all, there are frequent news shots of him holding the hand of a grandchild), I cannot  imagine him handling the complexities of It’s a Bird. . . . Its language and storytelling are too far removed from the non-avian tweets President Trump favors, and his pronouncements about racism and statues (as well as many other topics) show how poorly he understands or can work with shades of grey. I remain hopeful that this president’s popularity will wane enough to unseat him.

imagine him handling the complexities of It’s a Bird. . . . Its language and storytelling are too far removed from the non-avian tweets President Trump favors, and his pronouncements about racism and statues (as well as many other topics) show how poorly he understands or can work with shades of grey. I remain hopeful that this president’s popularity will wane enough to unseat him.

Saying something is “for the birds” is an old-fashioned put-down. It means “not worth much” and actually refers to the horse droppings on city streets that birds once ate. (So my saying that President Trump’s policies are “for the birds” would not be a polite and positive comment on his environmental views.) Today, however, I highlight two recent works—a graphic novel and a picture book—whose positive focus is on (or for) birds. Moreover, through their enchanting arrays of words and images, these books go beyond their avian story lines to raise other intriguing, meaningful ideas for readers. Tweens on up will appreciate the graphic novel Audubon, On the Wings of the World (2016; 2017), while readers as young as four will enjoy the picture book The Fog (2017).

Saying something is “for the birds” is an old-fashioned put-down. It means “not worth much” and actually refers to the horse droppings on city streets that birds once ate. (So my saying that President Trump’s policies are “for the birds” would not be a polite and positive comment on his environmental views.) Today, however, I highlight two recent works—a graphic novel and a picture book—whose positive focus is on (or for) birds. Moreover, through their enchanting arrays of words and images, these books go beyond their avian story lines to raise other intriguing, meaningful ideas for readers. Tweens on up will appreciate the graphic novel Audubon, On the Wings of the World (2016; 2017), while readers as young as four will enjoy the picture book The Fog (2017).  Created by French author Fabien Grolleau and Belgian illustrator Jerem Royer (and translated into English by Etienne Gilfillan), Audubon, On the Wings of the World is the life story of one of France’s most notable immigrants to the U.S., John James Audubon (1785 – 1851). Today Audubon is renowned for the lifelike, extensive images reproduced in his masterwork, Birds of America (1827 – 1839). It is considered one of the world’s greatest ornithological studies. (Some of its illustrations appear in the graphic novel’s End Notes. All are also now available

Created by French author Fabien Grolleau and Belgian illustrator Jerem Royer (and translated into English by Etienne Gilfillan), Audubon, On the Wings of the World is the life story of one of France’s most notable immigrants to the U.S., John James Audubon (1785 – 1851). Today Audubon is renowned for the lifelike, extensive images reproduced in his masterwork, Birds of America (1827 – 1839). It is considered one of the world’s greatest ornithological studies. (Some of its illustrations appear in the graphic novel’s End Notes. All are also now available  about how scientific passion and artistic obsession can take hold of a person, separating him from family bonds and social conventions, as it is about Audubon’s achievements. Grolleau and Royer wow readers with their multiple accomplishments here: sophisticated storytelling that smoothly uses images to convey emotion and mental state as well as factual details.

about how scientific passion and artistic obsession can take hold of a person, separating him from family bonds and social conventions, as it is about Audubon’s achievements. Grolleau and Royer wow readers with their multiple accomplishments here: sophisticated storytelling that smoothly uses images to convey emotion and mental state as well as factual details. way. For instance, the book’s opening scenes on the stormy Mississippi River reoccur later in the novel, shown from a different angle. This technique will intrigue some readers but may put off others. Similarly, some readers may find much to ponder in how obsessed Audubon, hearing a strange bird call, can leave his wife mid-sentence, just as she is telling him she is again pregnant. Other readers may simply be dismayed or appalled. (We see Audubon leaving his family on their own for years at a time.) The novel’s images also clearly show, however, that Audubon was equally hard on himself in his scientific pursuits and artistic endeavors.

way. For instance, the book’s opening scenes on the stormy Mississippi River reoccur later in the novel, shown from a different angle. This technique will intrigue some readers but may put off others. Similarly, some readers may find much to ponder in how obsessed Audubon, hearing a strange bird call, can leave his wife mid-sentence, just as she is telling him she is again pregnant. Other readers may simply be dismayed or appalled. (We see Audubon leaving his family on their own for years at a time.) The novel’s images also clearly show, however, that Audubon was equally hard on himself in his scientific pursuits and artistic endeavors. points, Audubon starves, purchasing paints rather than food with his limited money. Later, in his final years and days, when he is afflicted with dementia, we see how Audubon envisions himself turning into a bird. We also see how his family has come to reconcile themselves with the impact of Audubon’s unswerving obsessions on their lives. Wordless panels and sequences of wordless pages are eloquent throughout this novel. Water colors softly color its pages, where street and nautical scenes, bird and human bodies are precisely drawn but human features are cartoon-like. (On the Wings of the World won a European comics award for its success with this drawing style, known in French as claire ligne [clear line].)

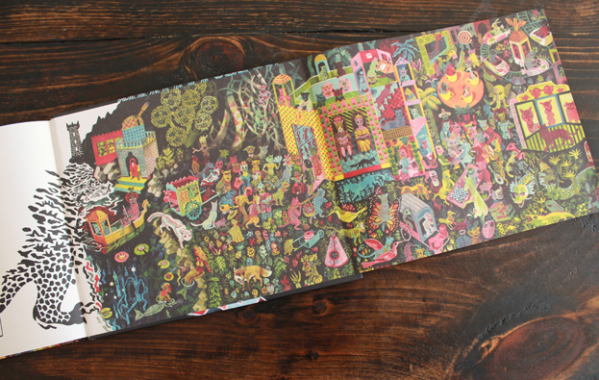

points, Audubon starves, purchasing paints rather than food with his limited money. Later, in his final years and days, when he is afflicted with dementia, we see how Audubon envisions himself turning into a bird. We also see how his family has come to reconcile themselves with the impact of Audubon’s unswerving obsessions on their lives. Wordless panels and sequences of wordless pages are eloquent throughout this novel. Water colors softly color its pages, where street and nautical scenes, bird and human bodies are precisely drawn but human features are cartoon-like. (On the Wings of the World won a European comics award for its success with this drawing style, known in French as claire ligne [clear line].) Readers are left to wonder whether the ornithologist sees more or less than the rest of us, whether he is insightful or self-deluded, through Royer’s depiction of some fantastic elements. There appear at one point to be mermaids in the Mississippi, while a whole new Bear constellation seems etched into one night-time sky. Some panels feature montages, showing sequential events all seeming to take place in a circle outside of time. One of these large panels features a variety of creatures, including a squirrel and warbler, which Audubon imagines watching him as closely as he has observed them!

Readers are left to wonder whether the ornithologist sees more or less than the rest of us, whether he is insightful or self-deluded, through Royer’s depiction of some fantastic elements. There appear at one point to be mermaids in the Mississippi, while a whole new Bear constellation seems etched into one night-time sky. Some panels feature montages, showing sequential events all seeming to take place in a circle outside of time. One of these large panels features a variety of creatures, including a squirrel and warbler, which Audubon imagines watching him as closely as he has observed them!  Such reversal of observer with observed is the premise of the picture book I am pleased to discuss today. The Fog (2017), written by award-winning Kyo Maclear and illustrated by Kenard Pak, is told from the view of Warble, a small yellow bird who is “a devoted human watcher”! Warble has identified hundreds of these fascinating creatures, numbering each one and labelling it by its observable characteristics. Besides delightful interior images of Warble’s observations, the book’s end papers are filled with images—and their accompanying mock-serious descriptions—of more than a dozen identifiably distinct human “types.” Readers young and old will laugh at Pak’s charmingly penciled, then computer-manipulated illustrations of such figures as # 663 SPOTTED AUDIOPHILIC FEMALE (JUVENILE), #667 SILVER-CRESTED CLAPPER (ELDER), AND #674 SWIFT RED-CAPPED PITCHER. Yet The Fog is not just humorous but looks at what happens when Warble’s world experiences a mysterious, dramatic change.

Such reversal of observer with observed is the premise of the picture book I am pleased to discuss today. The Fog (2017), written by award-winning Kyo Maclear and illustrated by Kenard Pak, is told from the view of Warble, a small yellow bird who is “a devoted human watcher”! Warble has identified hundreds of these fascinating creatures, numbering each one and labelling it by its observable characteristics. Besides delightful interior images of Warble’s observations, the book’s end papers are filled with images—and their accompanying mock-serious descriptions—of more than a dozen identifiably distinct human “types.” Readers young and old will laugh at Pak’s charmingly penciled, then computer-manipulated illustrations of such figures as # 663 SPOTTED AUDIOPHILIC FEMALE (JUVENILE), #667 SILVER-CRESTED CLAPPER (ELDER), AND #674 SWIFT RED-CAPPED PITCHER. Yet The Fog is not just humorous but looks at what happens when Warble’s world experiences a mysterious, dramatic change.

will delight here in recognizing what Warble does not: his new friend, with her own binoculars, is a bird-watcher. Working together, they send a message about the fog out into the world. Replies eventually come back, letting them know that other parts of the world have also distressingly been obscured. Then, the fog slowly lifts as mysteriously as it had appeared. Warble and his human friend remain close, though, enjoying each other’s company and their restored view of wonderful nature.

will delight here in recognizing what Warble does not: his new friend, with her own binoculars, is a bird-watcher. Working together, they send a message about the fog out into the world. Replies eventually come back, letting them know that other parts of the world have also distressingly been obscured. Then, the fog slowly lifts as mysteriously as it had appeared. Warble and his human friend remain close, though, enjoying each other’s company and their restored view of wonderful nature.  reviewers have noted that its global fog may represent climate change, so evident these days in our real-life Arctic and Antarctic “icy lands.” In an interview, author Maclear acknowledges that this fog may also represent a state of mind—depression or anxiety, which lessen when one connects with others. Maclear says that the impact of such moods, and how to manage them, are themes she has dealt with in her

reviewers have noted that its global fog may represent climate change, so evident these days in our real-life Arctic and Antarctic “icy lands.” In an interview, author Maclear acknowledges that this fog may also represent a state of mind—depression or anxiety, which lessen when one connects with others. Maclear says that the impact of such moods, and how to manage them, are themes she has dealt with in her  Perhaps as another way to manage mood, Maclear reveals how much she enjoys collaborating with illustrators in her many

Perhaps as another way to manage mood, Maclear reveals how much she enjoys collaborating with illustrators in her many  North America. The Audubon Society produces more detailed regional field guides for North America, as well as hosting a

North America. The Audubon Society produces more detailed regional field guides for North America, as well as hosting a  June brings proud smiles and commencement speeches for graduates of all ages. For many older grads, another rite of passage will soon follow: leaving home for college or that first full-time job. At least, this is the idealized version of how teens leave the safety of their family homes for the wider world. As we see in a deeply satisfying new graphic novel, not all teens have such good fortune. Readers tween on up will find much to enjoy and ponder in Soupy Leaves Home (2017). It does a great job making its 1930s USA setting accessible to contemporary readers while highlighting emotions and ideas not limited to one time or place. And—since it shows an individual coping with and surmounting personal obstacles—Soupy Leaves Home is a tonic that eases today’s too-often sickening nightly news. Its straightforward, hopeful sentiment is not trumpery.

June brings proud smiles and commencement speeches for graduates of all ages. For many older grads, another rite of passage will soon follow: leaving home for college or that first full-time job. At least, this is the idealized version of how teens leave the safety of their family homes for the wider world. As we see in a deeply satisfying new graphic novel, not all teens have such good fortune. Readers tween on up will find much to enjoy and ponder in Soupy Leaves Home (2017). It does a great job making its 1930s USA setting accessible to contemporary readers while highlighting emotions and ideas not limited to one time or place. And—since it shows an individual coping with and surmounting personal obstacles—Soupy Leaves Home is a tonic that eases today’s too-often sickening nightly news. Its straightforward, hopeful sentiment is not trumpery. This tale of seventeen year-old Pearl, who disguises herself as a boy and takes to the rails as a hobo named “Soupy,” fleeing her abusive father’s fists, began as personal therapy for its award-winning author Cecil Castelluci. In interviews, Castelluci has described how she latched onto researching

This tale of seventeen year-old Pearl, who disguises herself as a boy and takes to the rails as a hobo named “Soupy,” fleeing her abusive father’s fists, began as personal therapy for its award-winning author Cecil Castelluci. In interviews, Castelluci has described how she latched onto researching  Color is key in this novel. A changing array of richly-saturated monochrome pages conveys both the intensity and the progress of Soupy’s literal and emotional travels. As the young hobo begins to open up to the world, some panels and the less frequent full-page and double-page spreads also open up to two or more colors. In one such spread, Soupy comes to realize that, like “mulligan stew . . . . [t]he most important ingredient of all” in life “is kindness and an ear to the person everyone shuns.” Other dual or tri-colored scenes show Soupy’s final courageous return home, once she realizes that “I have to go and face my things or else I’ll never be free.” There, as throughout the novel, joyful imaginings and dreams are depicted in multiple colors—as shapes and figures swirl fantastically through the air.

Color is key in this novel. A changing array of richly-saturated monochrome pages conveys both the intensity and the progress of Soupy’s literal and emotional travels. As the young hobo begins to open up to the world, some panels and the less frequent full-page and double-page spreads also open up to two or more colors. In one such spread, Soupy comes to realize that, like “mulligan stew . . . . [t]he most important ingredient of all” in life “is kindness and an ear to the person everyone shuns.” Other dual or tri-colored scenes show Soupy’s final courageous return home, once she realizes that “I have to go and face my things or else I’ll never be free.” There, as throughout the novel, joyful imaginings and dreams are depicted in multiple colors—as shapes and figures swirl fantastically through the air.  Illustrator Pimienta’s significant role in this novel is also evident in its many wordless pages and panels. We see Soupy’s fears and doubts in her deftly-etched features, as she reacts to and reflects on events. For instance, we see how she comes to call herself “Soupy.” When asked by other hobos for her name, disguised Pearl is ladling up some stew. That panel contains her one word reply, “Soupy,” which is confirmed by the next wordless panel, a close-up of her hands on that soup bowl. Similarly, we later see college student Pearl’s success as a well-rounded person depicted in her triumphant body language. She is posed as a confident traveler, her now woman-styled hair comfortably worn with “boyish” clothing. Pimienta more than fulfills author Castellucci’s goals for this novel.

Illustrator Pimienta’s significant role in this novel is also evident in its many wordless pages and panels. We see Soupy’s fears and doubts in her deftly-etched features, as she reacts to and reflects on events. For instance, we see how she comes to call herself “Soupy.” When asked by other hobos for her name, disguised Pearl is ladling up some stew. That panel contains her one word reply, “Soupy,” which is confirmed by the next wordless panel, a close-up of her hands on that soup bowl. Similarly, we later see college student Pearl’s success as a well-rounded person depicted in her triumphant body language. She is posed as a confident traveler, her now woman-styled hair comfortably worn with “boyish” clothing. Pimienta more than fulfills author Castellucci’s goals for this novel.  As Castellucci explains, having written all-prose as well as graphic novels, she chose to write this book as a graphic novel because “Soupy is kind of shut down [as a character] and a comic book allows you to have silence. It also allows you to have scope and vistas.” Those long views, Castelluci goes on to say, help communicate how different the 1930s were, particularly for hobo travelers, and are important as well for the “magical” imaginings of her characters. It is fascinating to learn how Castelluci collaborated with illustrator Pimienta. She outlined page content, but he determined panel placement and highlights. Castelluci says that with this “full collaboration,” she was able to take her deliberately overwritten pages and “throw out a lot of . . . text.” The remaining dialogue is lean and powerful. Pimienta himself says he was moved by the book’s “sweet” script, able to relate “to several of the characters, not just Soupy.” He researched online and through photographs not just general 1930s backgrounds but also specific locations for the small town details depicted in Soupy and Ramshackle’s country-wide travels. Castelluci provided information about hobo signs, which also appear in a useful appendix to the novel.

As Castellucci explains, having written all-prose as well as graphic novels, she chose to write this book as a graphic novel because “Soupy is kind of shut down [as a character] and a comic book allows you to have silence. It also allows you to have scope and vistas.” Those long views, Castelluci goes on to say, help communicate how different the 1930s were, particularly for hobo travelers, and are important as well for the “magical” imaginings of her characters. It is fascinating to learn how Castelluci collaborated with illustrator Pimienta. She outlined page content, but he determined panel placement and highlights. Castelluci says that with this “full collaboration,” she was able to take her deliberately overwritten pages and “throw out a lot of . . . text.” The remaining dialogue is lean and powerful. Pimienta himself says he was moved by the book’s “sweet” script, able to relate “to several of the characters, not just Soupy.” He researched online and through photographs not just general 1930s backgrounds but also specific locations for the small town details depicted in Soupy and Ramshackle’s country-wide travels. Castelluci provided information about hobo signs, which also appear in a useful appendix to the novel. Mature tweens and teen readers interested in hobo life and/or Depression era USA might appreciate two other, hard-hitting graphic novels on this topic. The multiple award-winning Kings in Disguise (1988; 2006) and its sequel On the Ropes (2013), written by James Vance and illustrated by Dan E. Burr, explore how labor problems—union organizing and strike-breaking—dramatically affect the life of teen-aged hobo Fred. Unlike Soupy, who comes from a relatively affluent home, Fred takes to the rails due to poverty and scarce jobs. Drawing upon real-life events between 1932 and 1937, these powerful, comparatively downbeat books were reviewed

Mature tweens and teen readers interested in hobo life and/or Depression era USA might appreciate two other, hard-hitting graphic novels on this topic. The multiple award-winning Kings in Disguise (1988; 2006) and its sequel On the Ropes (2013), written by James Vance and illustrated by Dan E. Burr, explore how labor problems—union organizing and strike-breaking—dramatically affect the life of teen-aged hobo Fred. Unlike Soupy, who comes from a relatively affluent home, Fred takes to the rails due to poverty and scarce jobs. Drawing upon real-life events between 1932 and 1937, these powerful, comparatively downbeat books were reviewed  Related works in a different storytelling medium—one in which the images move—include some Hollywood films. Author Castellucci cites The Journey of Natty Gann (1985) and Sullivan’s Travels (1941) as her movie inspiration, to which I would add director William Wellman’s classic film Wild Boys of the Road (1933). Despite its title, its main characters include a

Related works in a different storytelling medium—one in which the images move—include some Hollywood films. Author Castellucci cites The Journey of Natty Gann (1985) and Sullivan’s Travels (1941) as her movie inspiration, to which I would add director William Wellman’s classic film Wild Boys of the Road (1933). Despite its title, its main characters include a  We Minnesotans love tall tales—especially ones about Paul Bunyan. Kids read about how his huge feet supposedly stomped out our 10,000 lakes and how the giant chopped down thousands of trees with one ax stroke. The communities of Bemidji and Brainerd boast the largest statues of this lumberjack and his blue ox Babe, but other Minnesota towns also will be celebrating on June 28, now officially

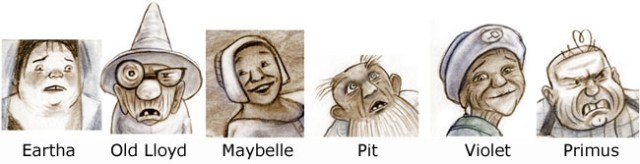

We Minnesotans love tall tales—especially ones about Paul Bunyan. Kids read about how his huge feet supposedly stomped out our 10,000 lakes and how the giant chopped down thousands of trees with one ax stroke. The communities of Bemidji and Brainerd boast the largest statues of this lumberjack and his blue ox Babe, but other Minnesota towns also will be celebrating on June 28, now officially  While individual states stake claims to particular tall tale heroes, such folk lore figures are found throughout America’s landscape. This phenomenon provides one lens through which to view a recent, highly-anticipated graphic novel, Cathy Malkasian’s Eartha (2017). Its titular central figure—the gentle giant Eartha—is as good-natured and righteous as Paul Bunyan and all his kind. She charges off to help others and fight villains as unselfishly and quickly as any legendary hero. Yet if we use only this lens we will distort author/illustrator Malkasian’s creation, which contains a more complicated world-view than the typical tall tale.

While individual states stake claims to particular tall tale heroes, such folk lore figures are found throughout America’s landscape. This phenomenon provides one lens through which to view a recent, highly-anticipated graphic novel, Cathy Malkasian’s Eartha (2017). Its titular central figure—the gentle giant Eartha—is as good-natured and righteous as Paul Bunyan and all his kind. She charges off to help others and fight villains as unselfishly and quickly as any legendary hero. Yet if we use only this lens we will distort author/illustrator Malkasian’s creation, which contains a more complicated world-view than the typical tall tale.

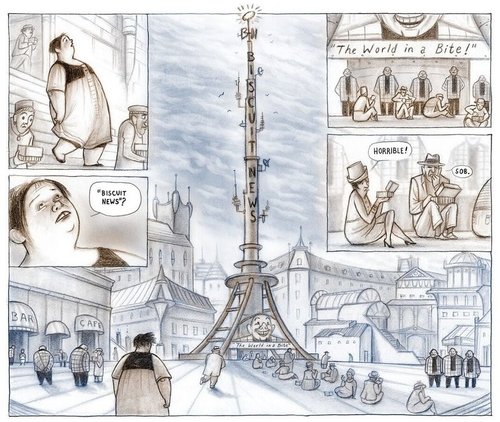

been the destination and resting place for physical manifestations of city-dwellers’ unrealized dreams. When Eartha bravely sets out for the City, she takes a rowboat. The highest level of technology in Echo Fjord is its massive drain pipes, while the City—with its stone and off-kilter stucco buildings reminiscent of 19th century Europe—deploys broadcast and aeronautical technology typical of the 1920s and ‘30s. Malkasian depicts a world outside of conventional time and history, where even the moon seems part of a fairy tale, oblong in shape over the Fjord but looming round over the City and its seaside.

been the destination and resting place for physical manifestations of city-dwellers’ unrealized dreams. When Eartha bravely sets out for the City, she takes a rowboat. The highest level of technology in Echo Fjord is its massive drain pipes, while the City—with its stone and off-kilter stucco buildings reminiscent of 19th century Europe—deploys broadcast and aeronautical technology typical of the 1920s and ‘30s. Malkasian depicts a world outside of conventional time and history, where even the moon seems part of a fairy tale, oblong in shape over the Fjord but looming round over the City and its seaside.  This fairy tale mode—with its presumptive audience of younger readers—is further suggested by the many wordless panels Malkasian uses to convey action. Shifts in perspective among these finely detailed images as well as their sequence are telling. For instance, when she sets out for the City, we see low, close views of determined Eartha as she drops into and wades along the reservoir leading to a drainage outlet. The giant hero fills each of these panels. When Eartha then slides into its long chute to reach the sea, we see her from behind and at a distance. Next, close-ups show Eartha straining to row the boat she luckily finds, struggling too not to capsize it. As she rows onward, side and overhead views drawn from a distance dramatically show how even enormous Eartha is dwarfed by the sea’s vastness.

This fairy tale mode—with its presumptive audience of younger readers—is further suggested by the many wordless panels Malkasian uses to convey action. Shifts in perspective among these finely detailed images as well as their sequence are telling. For instance, when she sets out for the City, we see low, close views of determined Eartha as she drops into and wades along the reservoir leading to a drainage outlet. The giant hero fills each of these panels. When Eartha then slides into its long chute to reach the sea, we see her from behind and at a distance. Next, close-ups show Eartha straining to row the boat she luckily finds, struggling too not to capsize it. As she rows onward, side and overhead views drawn from a distance dramatically show how even enormous Eartha is dwarfed by the sea’s vastness.

Ironically, given our president’s charges about official news organizations spreading “fake news,” it is those Tweet-like cookies which are phony. That gigantic radio receiver does not work! The cookies are the brainchild of a successful (if unhappy) baking magnate whose minions terrorize City dwellers as they bilk them of their possessions. The rule of law in the City has become “Acquisition is Justice.” As the United States’ chief executive today uses his business experience to gauge and set public policy, along the way tweeting unsubstantiated accusations about people and groups, the absurdities in this novel begin to seem frighteningly less fantastic and more probable.

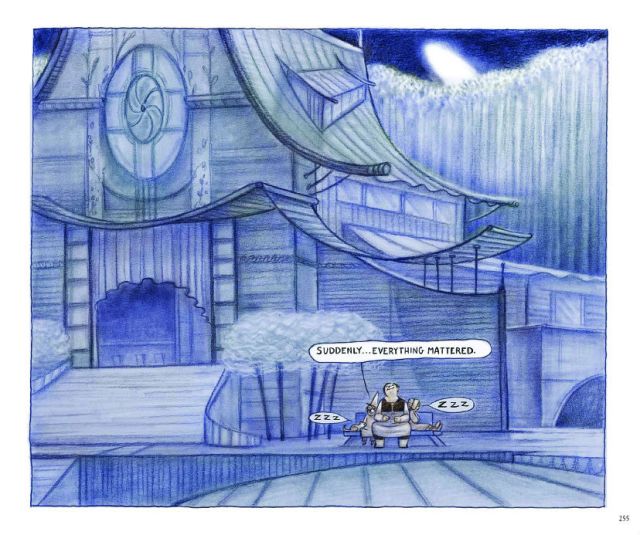

Ironically, given our president’s charges about official news organizations spreading “fake news,” it is those Tweet-like cookies which are phony. That gigantic radio receiver does not work! The cookies are the brainchild of a successful (if unhappy) baking magnate whose minions terrorize City dwellers as they bilk them of their possessions. The rule of law in the City has become “Acquisition is Justice.” As the United States’ chief executive today uses his business experience to gauge and set public policy, along the way tweeting unsubstantiated accusations about people and groups, the absurdities in this novel begin to seem frighteningly less fantastic and more probable. In Eartha, Malkasian resolves these problems with a fairy-tale like dovetailing of several plots, revealing connections and family relationships that aid gentle giant Eartha in her quest. She is able to help free the City from its web of deceitful news and return triumphantly to Echo Fjord and her true love Maybelle, to a world where now not just acquisition but “everything mattered.” These are the feel-good, if ambiguous, last words on the novel’s last page, depicting a snoozing Eartha as she pillows snoring Maybelle and their noisily slumbering friend Old Lloyd. They are content, even if readers are left to wonder about the ultimate impact of epitaphs, with their supposed end-of-life insights, that now blanket City streets in paper bulletins. Will people there take these sometimes cryptic messages to heart, and strive for more authentic goals than social prestige and wealth? We do not know for sure. It is a kind of hopefully uncertain ending that will resonate best with older readers.

In Eartha, Malkasian resolves these problems with a fairy-tale like dovetailing of several plots, revealing connections and family relationships that aid gentle giant Eartha in her quest. She is able to help free the City from its web of deceitful news and return triumphantly to Echo Fjord and her true love Maybelle, to a world where now not just acquisition but “everything mattered.” These are the feel-good, if ambiguous, last words on the novel’s last page, depicting a snoozing Eartha as she pillows snoring Maybelle and their noisily slumbering friend Old Lloyd. They are content, even if readers are left to wonder about the ultimate impact of epitaphs, with their supposed end-of-life insights, that now blanket City streets in paper bulletins. Will people there take these sometimes cryptic messages to heart, and strive for more authentic goals than social prestige and wealth? We do not know for sure. It is a kind of hopefully uncertain ending that will resonate best with older readers. For those seeking more clear-cut conclusions and purely humorous tales, this month readers young and old might relish several

For those seeking more clear-cut conclusions and purely humorous tales, this month readers young and old might relish several  delightful picture book additions to Paul Bunyan’s legend: The Bunyans (1996; 2006), written by award-winning Audrey Wood and illustrated by David Shannon, details the adventures of Paul, his wife Carrie McIntie, and their two enormous children. Minnesota author Marybeth Lorbiecki posits a different, bigger-than-life true love for Paul in Paul Bunyan’s

delightful picture book additions to Paul Bunyan’s legend: The Bunyans (1996; 2006), written by award-winning Audrey Wood and illustrated by David Shannon, details the adventures of Paul, his wife Carrie McIntie, and their two enormous children. Minnesota author Marybeth Lorbiecki posits a different, bigger-than-life true love for Paul in Paul Bunyan’s  Sweetheart (2007; 2011), illustrated by Renee Graef. There, gigantic Lucette Diana Kensack’s part – Ojibwe heritage is added to the tale. And another Minnesota author, Phyllis Root, creates a “little” sister for Paul in Paula Bunyan (2009), illustrated by Kevin O’Malley. Little Paula is only as tall as a pine tree!

Sweetheart (2007; 2011), illustrated by Renee Graef. There, gigantic Lucette Diana Kensack’s part – Ojibwe heritage is added to the tale. And another Minnesota author, Phyllis Root, creates a “little” sister for Paul in Paula Bunyan (2009), illustrated by Kevin O’Malley. Little Paula is only as tall as a pine tree! “May Day! May Day! May Day!”

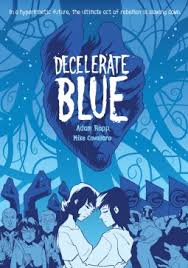

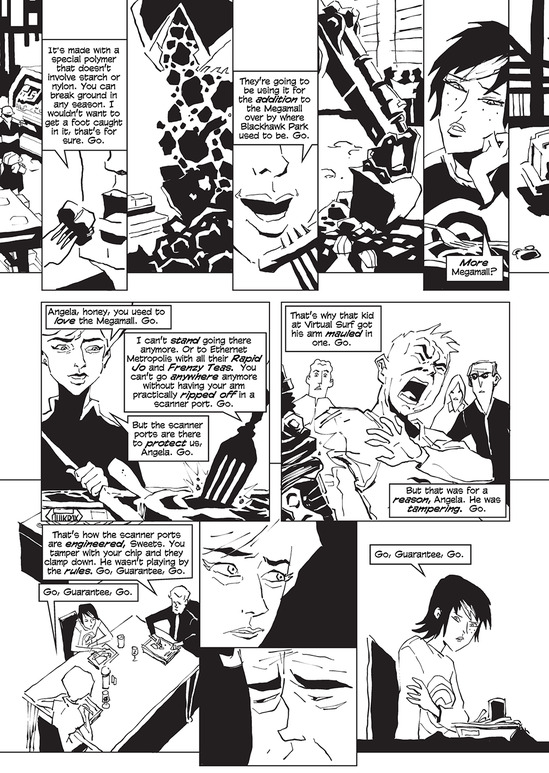

“May Day! May Day! May Day!”  What will today’s tomorrow look like? Author Adam Rapp and illustrator Mike Cavallaro see speed and consumerism dominating our world, with government forces regulating all aspects of daily life and social institutions. In this dystopia, only “Brief Lit” is taught in schools, and people must speak with contractions but without adjectives. The most popular movies are fifteen minutes long, upright beds encourage faster waking-up, and older folks whose heart rates are too slow are sent to isolated “reduction colonies.” Shopping at megamalls is considered a civic duty! Big business is so important that corporate logos, touting the speed of their products and services, are everywhere—even branded onto the bodies of animals.

What will today’s tomorrow look like? Author Adam Rapp and illustrator Mike Cavallaro see speed and consumerism dominating our world, with government forces regulating all aspects of daily life and social institutions. In this dystopia, only “Brief Lit” is taught in schools, and people must speak with contractions but without adjectives. The most popular movies are fifteen minutes long, upright beds encourage faster waking-up, and older folks whose heart rates are too slow are sent to isolated “reduction colonies.” Shopping at megamalls is considered a civic duty! Big business is so important that corporate logos, touting the speed of their products and services, are everywhere—even branded onto the bodies of animals.

Award-winning illustrator Cavallaro (whose work was also reviewed here in April, 2013) wholeheartedly committed himself to Rupp’s completed story. In a

Award-winning illustrator Cavallaro (whose work was also reviewed here in April, 2013) wholeheartedly committed himself to Rupp’s completed story. In a  It was Cavallaro’s decision to use black-and-white drawings throughout the work, without any shading, to indicate the stark demands and limited choices of this near-future. Author Rapp also agreed with the illustrator’s choice to use full-color at just two points—when Angela and Gladys first kiss and at the startling, ambiguous conclusion of the book. Rapp admits that his original conclusion spelled out the result of Angela’s final choice more clearly, but he was persuaded by Cavallaro to make the book’s conclusion more open-ended. What really is the result of Angela’s desperately taking an overdose of “decelerate blue,” the pill designed to help resistance fighters cope with limited oxygen in their underground society? How are we to interpret this final version of the repeated image of clasped hands forming a heart? Readers will have much to think about and discuss here.

It was Cavallaro’s decision to use black-and-white drawings throughout the work, without any shading, to indicate the stark demands and limited choices of this near-future. Author Rapp also agreed with the illustrator’s choice to use full-color at just two points—when Angela and Gladys first kiss and at the startling, ambiguous conclusion of the book. Rapp admits that his original conclusion spelled out the result of Angela’s final choice more clearly, but he was persuaded by Cavallaro to make the book’s conclusion more open-ended. What really is the result of Angela’s desperately taking an overdose of “decelerate blue,” the pill designed to help resistance fighters cope with limited oxygen in their underground society? How are we to interpret this final version of the repeated image of clasped hands forming a heart? Readers will have much to think about and discuss here.  Similarly, as one reviewer has noted, the alternative society this resistance movement devises has its own problems, in some ways placing demands on members not unlike the strictures of the corporate, speed-obsessed sunlit world above. I myself was disconcerted by the rebels’ proposed plan to take their doses of “decelerate blue” all at once, in a transforming community celebration. I did not immediately think of the Jonestown mass suicide, as that dismayed reviewer did, but the cult-like aspects of this ceremony did strike me. This too will provide food for thought.

Similarly, as one reviewer has noted, the alternative society this resistance movement devises has its own problems, in some ways placing demands on members not unlike the strictures of the corporate, speed-obsessed sunlit world above. I myself was disconcerted by the rebels’ proposed plan to take their doses of “decelerate blue” all at once, in a transforming community celebration. I did not immediately think of the Jonestown mass suicide, as that dismayed reviewer did, but the cult-like aspects of this ceremony did strike me. This too will provide food for thought. Even experienced gardeners may be fooled by hopes raised by fine April weather. Colorful buds promising full flowers can still be savaged this month by thundering rains, high winds, or even a sudden frost. Similarly, children and others may be lulled by the appearance and expectation of parental concern. After all, that is what every child deserves as well as needs. Yet some abused children refuse to admit or even recognize that a parent is harming them! Some abusive parents also do not acknowledge or perhaps understand the havoc they wreck. (One might make similar observations about the relationships between some political leaders and their followers.)

Even experienced gardeners may be fooled by hopes raised by fine April weather. Colorful buds promising full flowers can still be savaged this month by thundering rains, high winds, or even a sudden frost. Similarly, children and others may be lulled by the appearance and expectation of parental concern. After all, that is what every child deserves as well as needs. Yet some abused children refuse to admit or even recognize that a parent is harming them! Some abusive parents also do not acknowledge or perhaps understand the havoc they wreck. (One might make similar observations about the relationships between some political leaders and their followers.)  Belgian illustrator/author Brecht Evens’ Panther (2016, translated by Laura Watkinson and Michele Hutchinson) is so pretty that its terrors sneak up on us. Bold colors and multiple patterns taken from varied artistic traditions gradually reveal that young Christine’s imaginary playmate Panther is much more than a substitute for the pet cat who dies in chapter one. Panther seemingly represents Christine’s half-understood awareness of the sexual abuse her father is apparently inflicting on her. At first a (to us) suspiciously obliging playmate, changing storylines at young Christine’s every fantastic whim, this creature has an unnatural ability to literally change his spots and clothing which becomes increasingly more ominous. It parallels her father’s refusal to give

Belgian illustrator/author Brecht Evens’ Panther (2016, translated by Laura Watkinson and Michele Hutchinson) is so pretty that its terrors sneak up on us. Bold colors and multiple patterns taken from varied artistic traditions gradually reveal that young Christine’s imaginary playmate Panther is much more than a substitute for the pet cat who dies in chapter one. Panther seemingly represents Christine’s half-understood awareness of the sexual abuse her father is apparently inflicting on her. At first a (to us) suspiciously obliging playmate, changing storylines at young Christine’s every fantastic whim, this creature has an unnatural ability to literally change his spots and clothing which becomes increasingly more ominous. It parallels her father’s refusal to give  Christine a key to lock her bedroom, saying she is too young even as he says at bed time that she is “getting to be a big girl.” Christine’s terrified expression at that point solidifies our growing unease with Evens’ shifting palette. The cool, calm blues and soft reds of Christine’s everyday world no longer signal safety as we see objects there transformed into the hot tones and swirling images of Panther-dominated experiences.

Christine a key to lock her bedroom, saying she is too young even as he says at bed time that she is “getting to be a big girl.” Christine’s terrified expression at that point solidifies our growing unease with Evens’ shifting palette. The cool, calm blues and soft reds of Christine’s everyday world no longer signal safety as we see objects there transformed into the hot tones and swirling images of Panther-dominated experiences.  Panther himself darkens into deep black and white as he lulls Christine asleep, directing her to count backward from one hundred. By the book’s conclusion, what had been abstract overlays of multiple patterns, including some suggesting voyeuristic eyes and full-lipped mouths, are transformed into an abstract image of a rampaging black and white creature entering and then exploding out of Christine’s bedroom bureau. This seeming last page is really itself a physical overlay, opening from the book’s central spine to reveal two elaborate pages of full-colored details from the many stories Panther has spun to ensnare Christine. The easily-overlooked nature of this double spread sums up the techniques and hidden depths of incest here.

Panther himself darkens into deep black and white as he lulls Christine asleep, directing her to count backward from one hundred. By the book’s conclusion, what had been abstract overlays of multiple patterns, including some suggesting voyeuristic eyes and full-lipped mouths, are transformed into an abstract image of a rampaging black and white creature entering and then exploding out of Christine’s bedroom bureau. This seeming last page is really itself a physical overlay, opening from the book’s central spine to reveal two elaborate pages of full-colored details from the many stories Panther has spun to ensnare Christine. The easily-overlooked nature of this double spread sums up the techniques and hidden depths of incest here. The final pages of Panther confirm our worst fears, as this sly figure introduces new characters into so-called playtime. He tells Christine, “Here’s a game! If you stroke Giraffe, he changes shape. You want to try?” The eyeless, phallic-shaped depiction of Giraffe leaves little to the (mature) imagination here. Strange versions of other, once familiar stuffed toys also appear as Christine is nightmarishly held down just before a starkly-centered, black-and-white game of “doctor” appears to take place. Evens has said that his goal with this book was to “swing . . . a pendulum between desirable fun and absolute horror.” Using colored ink and markers, gouache, black ink, and crayons, he notes that his work here was influenced by “all kinds of children’s stories” but was specifically a “reaction to. . . the modern ones, where monsters are funny.” On both counts, Evens’ graphic novel is a gorgeously disturbing, unforgettable success.

The final pages of Panther confirm our worst fears, as this sly figure introduces new characters into so-called playtime. He tells Christine, “Here’s a game! If you stroke Giraffe, he changes shape. You want to try?” The eyeless, phallic-shaped depiction of Giraffe leaves little to the (mature) imagination here. Strange versions of other, once familiar stuffed toys also appear as Christine is nightmarishly held down just before a starkly-centered, black-and-white game of “doctor” appears to take place. Evens has said that his goal with this book was to “swing . . . a pendulum between desirable fun and absolute horror.” Using colored ink and markers, gouache, black ink, and crayons, he notes that his work here was influenced by “all kinds of children’s stories” but was specifically a “reaction to. . . the modern ones, where monsters are funny.” On both counts, Evens’ graphic novel is a gorgeously disturbing, unforgettable success.

emotional as well as physical child abuse. Goblet worked with translator Sophie Yanow to communicate here the difficult memories that she first began sketching out in 1995. Goblet also had her sometime romantic partner, author Guy Marc, write his “side” of some of their shared life together that she then went on to illustrate. The extent to which adult relationships figure in this memoir (including a page with nude figures in bed) make it more suited and meaningful for older teen readers.

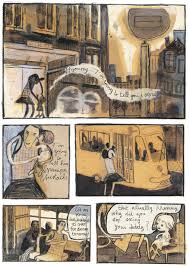

emotional as well as physical child abuse. Goblet worked with translator Sophie Yanow to communicate here the difficult memories that she first began sketching out in 1995. Goblet also had her sometime romantic partner, author Guy Marc, write his “side” of some of their shared life together that she then went on to illustrate. The extent to which adult relationships figure in this memoir (including a page with nude figures in bed) make it more suited and meaningful for older teen readers.  Using mainly pencil and charcoal on sepia or yellow-toned paper, Goblet’s palette is much more subdued and her drawing style looser and sometimes more angular than Brecht Evens. As she depicts how her alcoholic father was and remains an emotional bully and batterer, even mistreating his dog and ghost-faced second wife, Goblet varies the size and shape of letters in ways that make them shout or shriek. Now a parent herself, Goblet has a distant and uneasy relationship with her father. As we see, he has not changed, and Goblet rightly fears his interactions with her four-year old daughter. It is difficult to stand up to him when he begins to bully this child too. Goblet’s episodic depiction of her involvement with Guy Marc and with her daughter’s father also seems linked to the emotional upheavals of her childhood. Yet, while her blowhard father is emotionally abusive, we see in one shocking episode that it was Goblet’s mother who was physically abusive.

Using mainly pencil and charcoal on sepia or yellow-toned paper, Goblet’s palette is much more subdued and her drawing style looser and sometimes more angular than Brecht Evens. As she depicts how her alcoholic father was and remains an emotional bully and batterer, even mistreating his dog and ghost-faced second wife, Goblet varies the size and shape of letters in ways that make them shout or shriek. Now a parent herself, Goblet has a distant and uneasy relationship with her father. As we see, he has not changed, and Goblet rightly fears his interactions with her four-year old daughter. It is difficult to stand up to him when he begins to bully this child too. Goblet’s episodic depiction of her involvement with Guy Marc and with her daughter’s father also seems linked to the emotional upheavals of her childhood. Yet, while her blowhard father is emotionally abusive, we see in one shocking episode that it was Goblet’s mother who was physically abusive. Stressed both by her drunken husband’s meandering complaints and a young Dominque’s irritating play noises, her mother orders her up to the attic, not it seems for the first time, as Dominque wails, “[N]ot the attic. Nooo, not the attic!!” In stunning juxtapositions, we then see images of the televised car race crash her father is watching while we hear her mother’s announcement, “THAT’S WHAT WE HAVE TO DO WITH NASTY LITTLE GIRLS LIKE YOU . . .WE HAVE TO STRING THEM UP!!! . . . PUT YOUR HANDS IN THE AIR!!’ When we next see young Dominque, her face in tears and arms roped up to the attic ceiling, we hear not her whimpers but the televised reports of the crash. Even though a few pages later her mother apologizes to young Dominque, holding her on her lap and promising this punishment will not happen again, it hard for us (and perhaps Dominique Goblet herself) to believe her.

Stressed both by her drunken husband’s meandering complaints and a young Dominque’s irritating play noises, her mother orders her up to the attic, not it seems for the first time, as Dominque wails, “[N]ot the attic. Nooo, not the attic!!” In stunning juxtapositions, we then see images of the televised car race crash her father is watching while we hear her mother’s announcement, “THAT’S WHAT WE HAVE TO DO WITH NASTY LITTLE GIRLS LIKE YOU . . .WE HAVE TO STRING THEM UP!!! . . . PUT YOUR HANDS IN THE AIR!!’ When we next see young Dominque, her face in tears and arms roped up to the attic ceiling, we hear not her whimpers but the televised reports of the crash. Even though a few pages later her mother apologizes to young Dominque, holding her on her lap and promising this punishment will not happen again, it hard for us (and perhaps Dominique Goblet herself) to believe her.  leggings that Goblet “can do magic.” Yet all Goblet actually has done is reverse the leggings so their holes are out of sight! Such trust and love for a seemingly all-powerful parent emphasizes what is crushed when mothers or fathers abuse their children. The effects may well last years, just as the amorphous grey images of past loves “haunt” pages in this memoir. Has the adult Goblet overcome her assorted traumas? In her acknowledgments, perhaps crediting all the emotional abuse her mother herself experienced, the author/illustrator includes thanks to “. . . my mother, for whom I have lots of love and who, I hope, will consider this book an homage.” Goblet does not mention her father. And the possibility of stable romantic love remains unknown, just like the condition of an injured bird in the memoir’s last pages, set free only to fly out-of-sight.

leggings that Goblet “can do magic.” Yet all Goblet actually has done is reverse the leggings so their holes are out of sight! Such trust and love for a seemingly all-powerful parent emphasizes what is crushed when mothers or fathers abuse their children. The effects may well last years, just as the amorphous grey images of past loves “haunt” pages in this memoir. Has the adult Goblet overcome her assorted traumas? In her acknowledgments, perhaps crediting all the emotional abuse her mother herself experienced, the author/illustrator includes thanks to “. . . my mother, for whom I have lots of love and who, I hope, will consider this book an homage.” Goblet does not mention her father. And the possibility of stable romantic love remains unknown, just like the condition of an injured bird in the memoir’s last pages, set free only to fly out-of-sight. My attentive husband’s noting new arrivals in a university library led me to the final book in today’s posting. The Tale of One Bad Rat (1995; 2010), by acclaimed British illustrator/author Bryan Talbot, is both more forthright and more hopeful about the facts of child abuse and about survivors’ ability with help to overcome this trauma. Its central character has been sexually abused for years by her father and emotionally abused by her mother. Since its initial publication, this moving, award-winning account of 16 year-old runaway Helen has been reprinted in more than a dozen countries and used in multiple child abuse centers and literacy programs. Yet it is this novel’s artistry rather than didactic contact that makes it so memorable and satisfying for readers in any context.

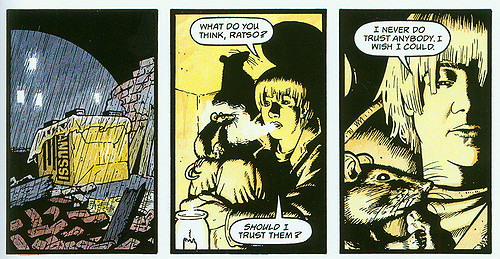

My attentive husband’s noting new arrivals in a university library led me to the final book in today’s posting. The Tale of One Bad Rat (1995; 2010), by acclaimed British illustrator/author Bryan Talbot, is both more forthright and more hopeful about the facts of child abuse and about survivors’ ability with help to overcome this trauma. Its central character has been sexually abused for years by her father and emotionally abused by her mother. Since its initial publication, this moving, award-winning account of 16 year-old runaway Helen has been reprinted in more than a dozen countries and used in multiple child abuse centers and literacy programs. Yet it is this novel’s artistry rather than didactic contact that makes it so memorable and satisfying for readers in any context.  Many wordless panels, along with succinct dialogue, communicate Helen’s physical and mental travels as she arrives in London, living homeless there until her inner demons drive her almost by accident to the Lake Country district made famous in part by her favorite childhood author/illustrator, Beatrix Potter. As Helen says to herself at one point about the sexual abuse she suffered for years, “I just can’t seem to get Dad out of my head.” Yet she succeeds—through emotional support, books about abuse, and talking about and confronting her parents—in finally doing just that. At first unable to permit any physical touch, Helen at this book’s end is able to hug those who have helped her. The healing, peaceful environment of the Lake District is also a boon here, as are the animal tales created by Beatrix Potter, herself a survivor of emotional abuse. These tales are what in part inspired Helen to rescue and make a pet of one of her school’s lab rats.

Many wordless panels, along with succinct dialogue, communicate Helen’s physical and mental travels as she arrives in London, living homeless there until her inner demons drive her almost by accident to the Lake Country district made famous in part by her favorite childhood author/illustrator, Beatrix Potter. As Helen says to herself at one point about the sexual abuse she suffered for years, “I just can’t seem to get Dad out of my head.” Yet she succeeds—through emotional support, books about abuse, and talking about and confronting her parents—in finally doing just that. At first unable to permit any physical touch, Helen at this book’s end is able to hug those who have helped her. The healing, peaceful environment of the Lake District is also a boon here, as are the animal tales created by Beatrix Potter, herself a survivor of emotional abuse. These tales are what in part inspired Helen to rescue and make a pet of one of her school’s lab rats.

course, an homage to Beatrix Potter’s many small masterpieces, such as The Tale of Peter Rabbit and The Tale of Two Bad Mice.

course, an homage to Beatrix Potter’s many small masterpieces, such as The Tale of Peter Rabbit and The Tale of Two Bad Mice. Going nuclear? A recent, award-winning picture book; another acclaimed, older picture book; and some classic and in-progress graphic novels remind us just how terrible this military choice has been. These works center upon the World War II atomic devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Last month’s visit of Japanese Prime Minister Abe to the U. S., along with President Trump’s ongoing, careless remarks about

Going nuclear? A recent, award-winning picture book; another acclaimed, older picture book; and some classic and in-progress graphic novels remind us just how terrible this military choice has been. These works center upon the World War II atomic devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Last month’s visit of Japanese Prime Minister Abe to the U. S., along with President Trump’s ongoing, careless remarks about  Survivors of atomic bombing eloquently testify to its horrors. Sachiko: A Nagasaki Bomb Survivor’s Story (2016), written by Caren Stelson, recently won a Silbert Honor Award among other accolades for its sensitive rendering of Sachiko Yusui’s experiences. Six years old in 1945 when the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Japan, Sachiko remarkably survived this attack but has been affected lifelong by it and its aftermath. A city in ruins and chaos; family deaths; radiation sickness and later cancer; and social stigma within Japan are all described here.

Survivors of atomic bombing eloquently testify to its horrors. Sachiko: A Nagasaki Bomb Survivor’s Story (2016), written by Caren Stelson, recently won a Silbert Honor Award among other accolades for its sensitive rendering of Sachiko Yusui’s experiences. Six years old in 1945 when the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Japan, Sachiko remarkably survived this attack but has been affected lifelong by it and its aftermath. A city in ruins and chaos; family deaths; radiation sickness and later cancer; and social stigma within Japan are all described here. An eerie, blinding light burst in the sky. Reds, blues, greens spiraled. Hot, deafening, hurricane-force winds roared, and at the center of the explosion, a giant fireball flamed, hotter than the surface of the sun.

An eerie, blinding light burst in the sky. Reds, blues, greens spiraled. Hot, deafening, hurricane-force winds roared, and at the center of the explosion, a giant fireball flamed, hotter than the surface of the sun. a memorable body of works by survivors. The simpler, shorter text of Junko Morimoto’s picture book My Hiroshima (1992; 2014) makes it more accessible to younger, elementary school readers than Sachiko’s biography. Yet this author/illustrator’s sparse words combine eloquently with her powerfully drawn images, moving readers of all ages.

a memorable body of works by survivors. The simpler, shorter text of Junko Morimoto’s picture book My Hiroshima (1992; 2014) makes it more accessible to younger, elementary school readers than Sachiko’s biography. Yet this author/illustrator’s sparse words combine eloquently with her powerfully drawn images, moving readers of all ages.  of the bomb mushrooming in a bright blue sky, bracketed top and bottom by darker flurries of explosively whirling, broken bodies—is stunning in design and execution. Some of these images in rearranged order appear in an affecting 2012 interview with Junko Morimoto. Available

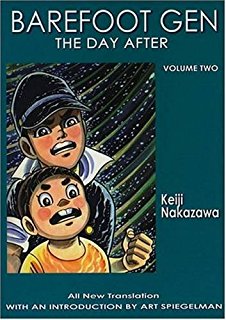

of the bomb mushrooming in a bright blue sky, bracketed top and bottom by darker flurries of explosively whirling, broken bodies—is stunning in design and execution. Some of these images in rearranged order appear in an affecting 2012 interview with Junko Morimoto. Available  its author/illustrator’s experiences as a six-year-old (here named “Gen”) when the A-bomb hit. He saw and heard his father and brother die in its immediate aftermath, pinned under remnants of their wooden house as it burned. Keiji and his mother were unable to rescue them. This scene, along with the burned, mutilated bodies of other survivors, figures on the final pages of volume one, A Cartoon History of Hiroshima. Volume two, The Day After, continues to depict the horrific physical aftermath of the attack, along with showing the ways in which survivors helped or refused to help others. The blunt, bold-lined images and stark narrative here make this classic series, translated into several languages, best suited to readers tween and older. Later volumes dealing with post World War II Japanese society would similarly be of most interest to these older readers.

its author/illustrator’s experiences as a six-year-old (here named “Gen”) when the A-bomb hit. He saw and heard his father and brother die in its immediate aftermath, pinned under remnants of their wooden house as it burned. Keiji and his mother were unable to rescue them. This scene, along with the burned, mutilated bodies of other survivors, figures on the final pages of volume one, A Cartoon History of Hiroshima. Volume two, The Day After, continues to depict the horrific physical aftermath of the attack, along with showing the ways in which survivors helped or refused to help others. The blunt, bold-lined images and stark narrative here make this classic series, translated into several languages, best suited to readers tween and older. Later volumes dealing with post World War II Japanese society would similarly be of most interest to these older readers. through a nightmare of depression after that and felt it was my responsibility to tell everybody about this book and relay what had happened [in Hiroshima].” She was even more horrified when a few years later the U.S. became involved in wars in the Middle East. Fortunately, Barefoot Gen still later also had a positive impact on Telgemeier. She says that it taught her that comics “were one of the most powerful mediums to tell a story. I still carry that philosophy with me, that comics can do so much.”

through a nightmare of depression after that and felt it was my responsibility to tell everybody about this book and relay what had happened [in Hiroshima].” She was even more horrified when a few years later the U.S. became involved in wars in the Middle East. Fortunately, Barefoot Gen still later also had a positive impact on Telgemeier. She says that it taught her that comics “were one of the most powerful mediums to tell a story. I still carry that philosophy with me, that comics can do so much.”  publication. Rather than bombs, it deals with nuclear power plants. In 2011, an earthquake and tsunami caused the Fukushima nuclear power plant in northern Japan to have three dangerous melt downs. Results of the radiation spewed out then are still being analyzed and debated. Author/illustrator Kazuto Tatsuta says that Ichi-F: A Worker’s Graphic Memoir of the Nuclear Power Plant (2015; 2017) is about daily life during the clean-up rather than the melt-downs themselves. Since nuclear power plants are a controversial topic world-wide, I am curious to see how and if this graphic novel remains as neutrally focused as its creator claims it is. Whether the topic is atomic bombs or atomic power plants, it is hard not to “go nuclear” when considering all the moral issues, political problems, and practical dangers these scientific achievements pose.