Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa, Winter Solstice, and other festive occasions . . . .

Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa, Winter Solstice, and other festive occasions . . . .

Two recent, compelling fairy tale volumes would make excellent gifts this holiday season. Matt Phelan’s Snow White: A Graphic Novel (2016) and Shaun Tan’s The Singing Bones (2015; 2016) are my enchanting focus today. Viewed separately or together, these books’ very different visual takes on classic stories demonstrate the wonderful breadth of unfettered imagination. Readers tween and up will appreciate these works rooted in folk tales first collected and published by the German brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm between 1812 and 1857. Those original Grimm stories were more violent and darker than many modern versions, watered down to be “suitable” for younger audiences—most famously by cartoon mogul Walt Disney. Phelan and Tan’s books, while not totally grim, remain truer to the original tales.

Award-winning author/illustrator Phelan (first reviewed here in December, 2013) drew on iconic photographs and films to set his Snow White primarily in Depression-era U.S.A. Living in 1918 New York City, Snow is a happy, well-to-do child whose later tribulations take place after the 1929 stock market crash precipitates the Depression. The black-and-white, sepia, or lightly tinted pages of this book reflect photos and movies typical in the 1920s and 1930s. Before full-color films became the norm, silent black-and-white movies sometimes had a few tinted scenes to reinforce changes in mood or action. Vivid color—the red of blood and the deceptive lushness of poisoned apples or lips—is used sparingly here, to great dramatic effect. Similarly, the book’s happy ending (after a dramatic kiss, not in a forest or castle but a department store window!) is reinforced by pages drawn and water-colored in a range of pastel colors.

Award-winning author/illustrator Phelan (first reviewed here in December, 2013) drew on iconic photographs and films to set his Snow White primarily in Depression-era U.S.A. Living in 1918 New York City, Snow is a happy, well-to-do child whose later tribulations take place after the 1929 stock market crash precipitates the Depression. The black-and-white, sepia, or lightly tinted pages of this book reflect photos and movies typical in the 1920s and 1930s. Before full-color films became the norm, silent black-and-white movies sometimes had a few tinted scenes to reinforce changes in mood or action. Vivid color—the red of blood and the deceptive lushness of poisoned apples or lips—is used sparingly here, to great dramatic effect. Similarly, the book’s happy ending (after a dramatic kiss, not in a forest or castle but a department store window!) is reinforced by pages drawn and water-colored in a range of pastel colors.

Phelan effectively updates and anchors Snow White to this specific time and place in many ways. Her evil stepmother is a Ziegfeld Follies star whose desire for the spotlight is exceeded only by her greed; here, she is inspired by messages from a seemingly demonic stock exchange ticker tape machine, rather than a magic mirror. Her plots, machinations, and evil deeds are effectively conveyed by telling close-ups, another cinematic technique Phelan employs. His knowledge and love of silent films is also evident in the many wordless scenes in the book, some as long as ten or twelve double spread pages. The electrifying end to that murderous Follies star’s schemes —in a chapter aptly titled “Up in Lights”—is almost totally wordless, yet very rich in emotion as well as fast-paced action. Sound-effect words and street signs, along with facial expressions, communicate so much in these pages, as they do throughout the book.

Phelan effectively updates and anchors Snow White to this specific time and place in many ways. Her evil stepmother is a Ziegfeld Follies star whose desire for the spotlight is exceeded only by her greed; here, she is inspired by messages from a seemingly demonic stock exchange ticker tape machine, rather than a magic mirror. Her plots, machinations, and evil deeds are effectively conveyed by telling close-ups, another cinematic technique Phelan employs. His knowledge and love of silent films is also evident in the many wordless scenes in the book, some as long as ten or twelve double spread pages. The electrifying end to that murderous Follies star’s schemes —in a chapter aptly titled “Up in Lights”—is almost totally wordless, yet very rich in emotion as well as fast-paced action. Sound-effect words and street signs, along with facial expressions, communicate so much in these pages, as they do throughout the book.

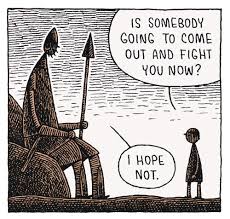

This story’s Depression-era characters include seven homeless boys, living hand-to-mouth on the streets and in a hobo encampment, who are Phelan’s fairy tale “dwarves,” sheltering, rescuing, and for a time mourning Snow White. Their initially suspicious, pugnacious faces are eloquent, even when all their leader will reveal about them is the dismissive, wary phrase, “We’re the Seven. That’s all you need to know.” Readers may become misty-eyed when each boy, mourning Snow’s apparent death, whispers his name into her ear.

Phelan strives for such emotional response in his works. In an interview , he has said “that emotional connection is . . . something I aspire to in my work.” That is why his drawing is not totally realistic in style: as he puts it, “I’ve always loved sketches and art that has a ‘just enough’ quality to it.” He adds that, rather than using a guide sketch, after much time in preparation and initial thumb-nail sketches (Snow White: A Graphic Novel took three years to complete), he draws freehand from those sketches, working “quickly on each panel. I want a certain energy to the line and the watercolor.” Phelan’s typical use of un-bordered, irregularly sized panels and double spread pages, some without any panels at all, adds to the vibrancy of his story-telling goals and technique.

Phelan strives for such emotional response in his works. In an interview , he has said “that emotional connection is . . . something I aspire to in my work.” That is why his drawing is not totally realistic in style: as he puts it, “I’ve always loved sketches and art that has a ‘just enough’ quality to it.” He adds that, rather than using a guide sketch, after much time in preparation and initial thumb-nail sketches (Snow White: A Graphic Novel took three years to complete), he draws freehand from those sketches, working “quickly on each panel. I want a certain energy to the line and the watercolor.” Phelan’s typical use of un-bordered, irregularly sized panels and double spread pages, some without any panels at all, adds to the vibrancy of his story-telling goals and technique.

While Matt Phelan avoided reading multiple written versions of Snow White, wanting “to approach the story fresh,” Shaun Tan’s fairy tale volume was inspired by the written word. Specifically, after designing the cover and a few internal illustrations for  a German language edition of Grimm’s fairy tales, Tan was hooked! That book was a translation of noted British author Philip Pullman’s Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm (Viking, 2012), which contained Pullman’s favorite fifty tales. Tan (reviewed here in August, 2014 and April, 2015) was so entranced by Pullman’s language and storytelling that he went on to identify and create sculptures in The Singing Bones for seventy-five Grimm tales. Tan’s book, however, does not contain complete versions of these tales. Instead, a significant passage from a tale appears on the left hand page, with Tan’s related sculpture appearing on the opposite right-hand page. Noted fairy tale scholar and translator Jack Zipes is the author of these passages, as well as the Annotated Index summarizing the tales’ plots.

a German language edition of Grimm’s fairy tales, Tan was hooked! That book was a translation of noted British author Philip Pullman’s Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm (Viking, 2012), which contained Pullman’s favorite fifty tales. Tan (reviewed here in August, 2014 and April, 2015) was so entranced by Pullman’s language and storytelling that he went on to identify and create sculptures in The Singing Bones for seventy-five Grimm tales. Tan’s book, however, does not contain complete versions of these tales. Instead, a significant passage from a tale appears on the left hand page, with Tan’s related sculpture appearing on the opposite right-hand page. Noted fairy tale scholar and translator Jack Zipes is the author of these passages, as well as the Annotated Index summarizing the tales’ plots.

Award-winning Tan’s imaginative take on each tale differs dramatically from Phelan’s. Rather than situating the tales in a particular time and place, Tan’s sculpture captures the emotional center of each story, recreating people, creatures, and items with minimal detail and dreamlike distortion. In his Afterward, Tan writes that he was “inspired by Inuit stone carvings and pre-Columbian clay figurines . . . .” He used papier-mache and air-dried clay, colored with acrylic paint, metal oxides, and shoe polish, to create his small-scale pieces. Elsewhere, Tan notes that some of his paper sculpting techniques were folk craft taught by his Malaysian/Chinese father. With input from his skilled photographer wife, Inari Kiuru, Tan then designed for The Singing Bones the photographed versions of his three-dimensional art.

Award-winning Tan’s imaginative take on each tale differs dramatically from Phelan’s. Rather than situating the tales in a particular time and place, Tan’s sculpture captures the emotional center of each story, recreating people, creatures, and items with minimal detail and dreamlike distortion. In his Afterward, Tan writes that he was “inspired by Inuit stone carvings and pre-Columbian clay figurines . . . .” He used papier-mache and air-dried clay, colored with acrylic paint, metal oxides, and shoe polish, to create his small-scale pieces. Elsewhere, Tan notes that some of his paper sculpting techniques were folk craft taught by his Malaysian/Chinese father. With input from his skilled photographer wife, Inari Kiuru, Tan then designed for The Singing Bones the photographed versions of his three-dimensional art.

These are powerful, haunting images. Tan embodies the story of Snow White in a sculpture of the evil queen or stepmother, red with violent envy; sharp-featured with consuming, murderous ambition; shadowed by pride which has made her spiked crown as large and important as her barely human head. His Hansel and Gretel are both too hungry and too greedy for sweets to see the dangerous, powerful witch lurking behind the

These are powerful, haunting images. Tan embodies the story of Snow White in a sculpture of the evil queen or stepmother, red with violent envy; sharp-featured with consuming, murderous ambition; shadowed by pride which has made her spiked crown as large and important as her barely human head. His Hansel and Gretel are both too hungry and too greedy for sweets to see the dangerous, powerful witch lurking behind the  seemingly harmless old woman who then invites them inside her candy-studded cottage. The reader, though, sees that monstrous figure as well as the cracks in the cottage, with its doorway that also resembles the opening of a clay oven. It is the weariness of toiling Cinderella, falling asleep inside the sooty bed of a fireless chimney, rather than her glass slipper and romance, that Tan emphasizes. And it is the dangerous naivety of Little Red Cap, contrasted with the wolf’s smug assurance and size, rather than her final rescue that Tan embodies in highlight. Readers will want to linger over these familiar tales, and also make good use of the index to discover the full stories behind the many compelling pieces born of lesser known tales.

seemingly harmless old woman who then invites them inside her candy-studded cottage. The reader, though, sees that monstrous figure as well as the cracks in the cottage, with its doorway that also resembles the opening of a clay oven. It is the weariness of toiling Cinderella, falling asleep inside the sooty bed of a fireless chimney, rather than her glass slipper and romance, that Tan emphasizes. And it is the dangerous naivety of Little Red Cap, contrasted with the wolf’s smug assurance and size, rather than her final rescue that Tan embodies in highlight. Readers will want to linger over these familiar tales, and also make good use of the index to discover the full stories behind the many compelling pieces born of lesser known tales.

Like author Neil Gaiman, who wrote the Foreword to The Singing Bones, I long to touch these pieces, to revel in their textures and also view them from different angles. My desire here is also fed by my own dabbling in clay this past year, producing pieces heavier on emotion than realism. It was researching folk tales for possible inspiration for my future sculptures that led me to discover Shaun Tan’s three-dimensional art! Now, I need to see which tales apart from the Grimm brothers might spark some more of my own amateur efforts. First up: a look into the folk tales of my own Eastern European Jewish heritage.

Like author Neil Gaiman, who wrote the Foreword to The Singing Bones, I long to touch these pieces, to revel in their textures and also view them from different angles. My desire here is also fed by my own dabbling in clay this past year, producing pieces heavier on emotion than realism. It was researching folk tales for possible inspiration for my future sculptures that led me to discover Shaun Tan’s three-dimensional art! Now, I need to see which tales apart from the Grimm brothers might spark some more of my own amateur efforts. First up: a look into the folk tales of my own Eastern European Jewish heritage.

Are you interested in other graphic works depicting folk or fairy tales from different traditions? There are many picture books depicting “Cinderella” stories around the globe. Ed Young’s award-winning Lon Po Po (1989;1996), set in China; John Steptoe’s acclaimed Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters (1978; 2008), set in Africa; and Tomie de Paola’s Adelita (2002;2004), set in Mexico, are only a few. I myself plan to catch up with an award-winning volume of Native American graphic folk tales, edited by Matt Dembicki, Trickster: Native American Tales, A Graphic Collection (2010). It features the combined efforts of Native storytellers with comic book artists.

Are you interested in other graphic works depicting folk or fairy tales from different traditions? There are many picture books depicting “Cinderella” stories around the globe. Ed Young’s award-winning Lon Po Po (1989;1996), set in China; John Steptoe’s acclaimed Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters (1978; 2008), set in Africa; and Tomie de Paola’s Adelita (2002;2004), set in Mexico, are only a few. I myself plan to catch up with an award-winning volume of Native American graphic folk tales, edited by Matt Dembicki, Trickster: Native American Tales, A Graphic Collection (2010). It features the combined efforts of Native storytellers with comic book artists.

Happy reading—and happy holidays!

Two graphic novelists were among the twenty-three creative people recently awarded an annual

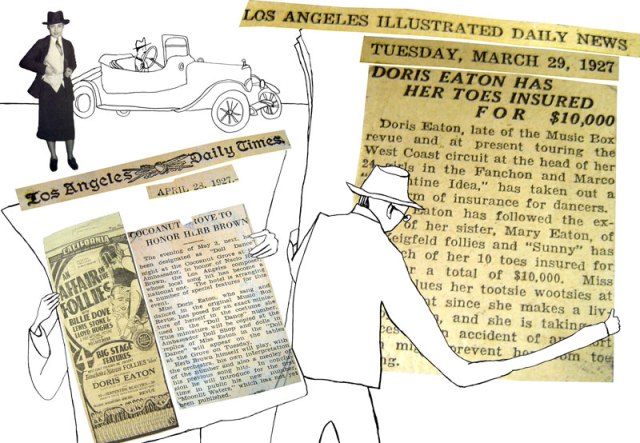

Two graphic novelists were among the twenty-three creative people recently awarded an annual  Redniss is an art professor who has been praised by the National Book Foundation for “marrying the graphic and visual arts with biography and cultural history.” Redniss herself

Redniss is an art professor who has been praised by the National Book Foundation for “marrying the graphic and visual arts with biography and cultural history.” Redniss herself  Redniss documents the different ways family members handled success and its loss, into and through the 1930s and 1940s, as the Great Depression and World War II impacted their lives. Giddy, silly, saucy, and even some sad images mark the passing decades. Her sisters and brothers faltered, some just having plain bad luck, while Doris went on to a new career and success as a dance instructor, working with the Arthur Murray chain of dance schools. Her passion for dance continued throughout her long life and her lengthy, complicated second marriage. Along the way, this trouper entered college as a 77 year old “freshman,” and became a college graduate at 88! The volume’s final pages include photographs of 100 year-old Doris onstage as well as of her musing about her life.

Redniss documents the different ways family members handled success and its loss, into and through the 1930s and 1940s, as the Great Depression and World War II impacted their lives. Giddy, silly, saucy, and even some sad images mark the passing decades. Her sisters and brothers faltered, some just having plain bad luck, while Doris went on to a new career and success as a dance instructor, working with the Arthur Murray chain of dance schools. Her passion for dance continued throughout her long life and her lengthy, complicated second marriage. Along the way, this trouper entered college as a 77 year old “freshman,” and became a college graduate at 88! The volume’s final pages include photographs of 100 year-old Doris onstage as well as of her musing about her life.

is to isolate them in the center of otherwise empty or nearly empty pages. The left hand side of one such spread states in black letters on a white page: WITH STRENGTH IN NUMBERS AND A SOLID PEDIGREE, THE EATONS SEEMED UNSTOPPABLE. The facing right-hand white page shows Doris with one of her brothers, with these ominous words as follow-up: BUT TIMES CHANGED. Redniss’ ability to identify and use apt words from interviews as well as printed sources is another storytelling strength she brings to this book (as well as her others).

is to isolate them in the center of otherwise empty or nearly empty pages. The left hand side of one such spread states in black letters on a white page: WITH STRENGTH IN NUMBERS AND A SOLID PEDIGREE, THE EATONS SEEMED UNSTOPPABLE. The facing right-hand white page shows Doris with one of her brothers, with these ominous words as follow-up: BUT TIMES CHANGED. Redniss’ ability to identify and use apt words from interviews as well as printed sources is another storytelling strength she brings to this book (as well as her others).  Print materials also complement images in Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie, A Tale of Love and Fallout (2010; 2011), another breathtaking biography, which was a finalist for the National Book Award. Here Redniss uses collage to show how Marie Sklodowska (1867 -1934) battled discrimination against women in science to become the degreed research partner (and later wife) of Pierre Curie. Together, the couple in 1903 earned a Nobel Prize in Physics for their discovery of radioactivity. After Pierre’s death, Marie Curie in 1911 earned an astonishing second Nobel Prize for her further work on the radioactive element radium.

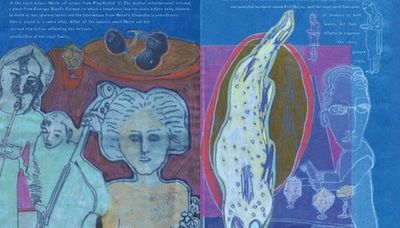

Print materials also complement images in Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie, A Tale of Love and Fallout (2010; 2011), another breathtaking biography, which was a finalist for the National Book Award. Here Redniss uses collage to show how Marie Sklodowska (1867 -1934) battled discrimination against women in science to become the degreed research partner (and later wife) of Pierre Curie. Together, the couple in 1903 earned a Nobel Prize in Physics for their discovery of radioactivity. After Pierre’s death, Marie Curie in 1911 earned an astonishing second Nobel Prize for her further work on the radioactive element radium.  her daughters, finding and losing another, somewhat scandalous love, and even contributing to France’s frontline efforts during World War I. Radioactive uses text deftly chosen from letters, journals, and other written accounts to tell a profound love story as well as a history of science. Moreover, the “fallout” of its subtitle extends beyond Marie Curie’s lifetime into the present day, as the book details the negative as well as positive results of the Curies’ discoveries. Redniss interposes accounts of nuclear bombs and accidents at nuclear power plants, as well as advances in nuclear medicine, smoothly into the book.

her daughters, finding and losing another, somewhat scandalous love, and even contributing to France’s frontline efforts during World War I. Radioactive uses text deftly chosen from letters, journals, and other written accounts to tell a profound love story as well as a history of science. Moreover, the “fallout” of its subtitle extends beyond Marie Curie’s lifetime into the present day, as the book details the negative as well as positive results of the Curies’ discoveries. Redniss interposes accounts of nuclear bombs and accidents at nuclear power plants, as well as advances in nuclear medicine, smoothly into the book. For the rich blue shades predominant here and the sometimes eerie images, which often seem to glow and resemble half-developed photographs or x-rays, Redniss used a specialized technique–cyantope printing. As she explains at the end of Radioactive and in a related

For the rich blue shades predominant here and the sometimes eerie images, which often seem to glow and resemble half-developed photographs or x-rays, Redniss used a specialized technique–cyantope printing. As she explains at the end of Radioactive and in a related  Similar thought went into Redniss’ choice of graphic techniques for her award-winning third book, Thunder & Lightning: Weather Past, Present, and Future (2015). Her author’s note explains that she selected copper plate etching (and its contemporary offshoot, polymer plate etching) as a tribute to the centuries of records kept by weather-studying scientists and artists. Master printers helped Redniss produce black and white prints, which she then hand-colored. The beautiful and totally wordless chapter 7, titled “Sky,” was hand-drawn by Redniss, using colorful oil pastels.

Similar thought went into Redniss’ choice of graphic techniques for her award-winning third book, Thunder & Lightning: Weather Past, Present, and Future (2015). Her author’s note explains that she selected copper plate etching (and its contemporary offshoot, polymer plate etching) as a tribute to the centuries of records kept by weather-studying scientists and artists. Master printers helped Redniss produce black and white prints, which she then hand-colored. The beautiful and totally wordless chapter 7, titled “Sky,” was hand-drawn by Redniss, using colorful oil pastels.  polluted city fog and Arctic “snow blindness.” Redniss illustrates the latter in four double spread pages, where we peer into soft grey-tones, attempting to make out the faint shapes there just as a snow-blind person might struggle to see in white-out conditions. Black is again used effectively as background to a typeface Redniss created herself for this book.

polluted city fog and Arctic “snow blindness.” Redniss illustrates the latter in four double spread pages, where we peer into soft grey-tones, attempting to make out the faint shapes there just as a snow-blind person might struggle to see in white-out conditions. Black is again used effectively as background to a typeface Redniss created herself for this book.

However one feels about such labels, I am glad the MacArthur Foundation award drew my attention to Lauren Redniss’ gifts. I intend to catch up with her earlier

However one feels about such labels, I am glad the MacArthur Foundation award drew my attention to Lauren Redniss’ gifts. I intend to catch up with her earlier  A spirited crowd welcomed author/illustrator Raina Telgemeier to the Twin Cities the other week. Tweens in family and class groups

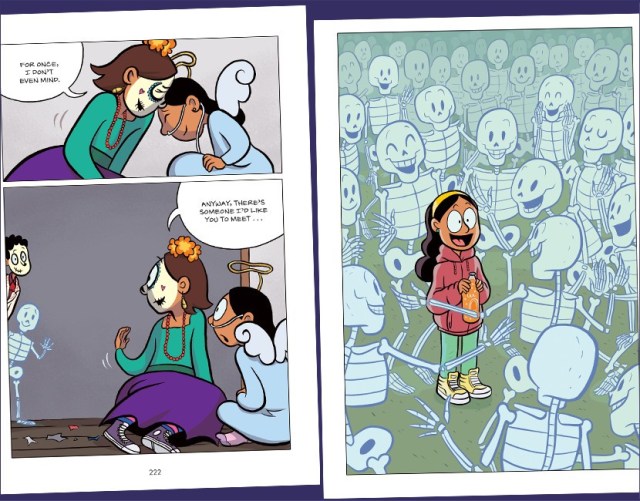

A spirited crowd welcomed author/illustrator Raina Telgemeier to the Twin Cities the other week. Tweens in family and class groups  The 6th grade protagonist in Ghosts, Catrina Allende-Delmar, is both skeptical and fearful of ghosts. She and younger sister Maya are not familiar with the Mexican-American traditions that their mother, the daughter of Mexican immigrants, shunned in her own youth. They do not know that, during the Day of the Dead, loved ones who have died are remembered with joy, honor, and affection. Music, festive food, and dancing are the background notes to this holiday now celebrated beyond Mexico, with Halloween’s fearsome skeletons figuratively transformed into lost loved ones. In Telgemeier’s fantastic novel, this transformation is a literal one, as the windy environs of Catrina and Maya’s new California hometown are filled with ghosts. They may be encountered even on ordinary days, not just during this community’s welcoming Dia de Los Muertos celebration.

The 6th grade protagonist in Ghosts, Catrina Allende-Delmar, is both skeptical and fearful of ghosts. She and younger sister Maya are not familiar with the Mexican-American traditions that their mother, the daughter of Mexican immigrants, shunned in her own youth. They do not know that, during the Day of the Dead, loved ones who have died are remembered with joy, honor, and affection. Music, festive food, and dancing are the background notes to this holiday now celebrated beyond Mexico, with Halloween’s fearsome skeletons figuratively transformed into lost loved ones. In Telgemeier’s fantastic novel, this transformation is a literal one, as the windy environs of Catrina and Maya’s new California hometown are filled with ghosts. They may be encountered even on ordinary days, not just during this community’s welcoming Dia de Los Muertos celebration.  and Maya because Maya has cystic fibrosis—a degenerative, fatal disease. As the younger girl poignantly tells Cat, “I have to talk to a ghost . . . . I want to know what happens when you die . . . . Dying isn’t pretend . . . .” Telgemeier’s story insightfully depicts how Maya’s illness has shaped family choices, and how—despite the love between the sisters—Cat sometimes resents the priority given to Maya’s needs. The author/illustrator also realistically depicts how cystic fibrosis typically affects its victims, the main ailment being difficulty in breathing. Ironically, it is breath or wind which also “gives life” to Telgemeier’s ghosts.

and Maya because Maya has cystic fibrosis—a degenerative, fatal disease. As the younger girl poignantly tells Cat, “I have to talk to a ghost . . . . I want to know what happens when you die . . . . Dying isn’t pretend . . . .” Telgemeier’s story insightfully depicts how Maya’s illness has shaped family choices, and how—despite the love between the sisters—Cat sometimes resents the priority given to Maya’s needs. The author/illustrator also realistically depicts how cystic fibrosis typically affects its victims, the main ailment being difficulty in breathing. Ironically, it is breath or wind which also “gives life” to Telgemeier’s ghosts.

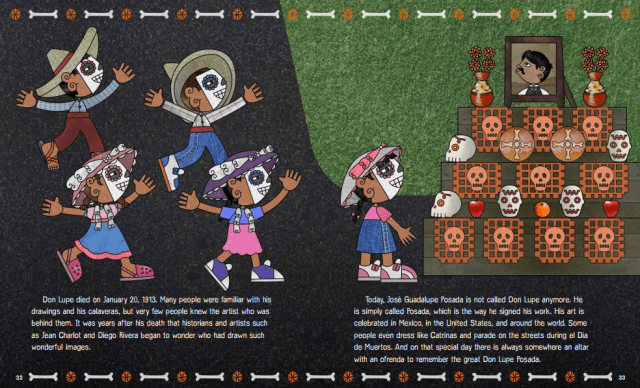

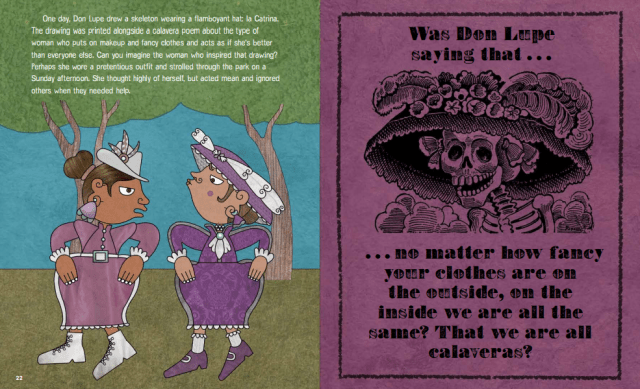

picture book biography, Funny Bones: Posada and His Day of the Dead Calaveras (2015). Cat and Maya’s welcoming (human) neighbors are named the Calaveras family. As Tonatiuh explains, the Spanish word calaveras literally means “skull.” Calaveras has also come to mean the satirical skeleton images, associated with the Day of the Dead, best known through the work of Mexican artist Jose Guadalupe Posada (1852 – 1913). Posada was himself no slouch in the humor department! He poked fun not only at politicians but at the vanity and foibles of wealthy and working class people too.

picture book biography, Funny Bones: Posada and His Day of the Dead Calaveras (2015). Cat and Maya’s welcoming (human) neighbors are named the Calaveras family. As Tonatiuh explains, the Spanish word calaveras literally means “skull.” Calaveras has also come to mean the satirical skeleton images, associated with the Day of the Dead, best known through the work of Mexican artist Jose Guadalupe Posada (1852 – 1913). Posada was himself no slouch in the humor department! He poked fun not only at politicians but at the vanity and foibles of wealthy and working class people too.  bones alternating with other emblems that indicate the passage of time—for instance, the pencils of Posada’s youth give way to inkpots as Tonituah describes how the artist began to etch his work. And even life’s ups and downs—growing families, disastrous floods, fame and success, war—are depicted with cohesive visual flair, with centered images often arranged in circles. I particularly relished the double page spreads showing how the Dia de Muertos was celebrated during Posada’s lifetime and Tonatiuh’s final imagining of what Posada’s calaveras might “look like nowadays.” Those roller blading and skateboarding skeletons are a hoot!

bones alternating with other emblems that indicate the passage of time—for instance, the pencils of Posada’s youth give way to inkpots as Tonituah describes how the artist began to etch his work. And even life’s ups and downs—growing families, disastrous floods, fame and success, war—are depicted with cohesive visual flair, with centered images often arranged in circles. I particularly relished the double page spreads showing how the Dia de Muertos was celebrated during Posada’s lifetime and Tonatiuh’s final imagining of what Posada’s calaveras might “look like nowadays.” Those roller blading and skateboarding skeletons are a hoot!

Here in the U.S., Labor Day weekend marks the unofficial end of summer and start of another school year. You probably know at least a few kids unhappy with this turn of events! Yet around the globe school remains an out-of-reach luxury for too many kids, many of whom labor in unsafe and unhealthy conditions. Still other young people world-wide are denied an education just because they are female. These inequities are the focus of today’s blog, which spotlights three excellent picture books. A

Here in the U.S., Labor Day weekend marks the unofficial end of summer and start of another school year. You probably know at least a few kids unhappy with this turn of events! Yet around the globe school remains an out-of-reach luxury for too many kids, many of whom labor in unsafe and unhealthy conditions. Still other young people world-wide are denied an education just because they are female. These inequities are the focus of today’s blog, which spotlights three excellent picture books. A  Award-winning author/illustrator Jeanette Winter has created an unusual as well as powerful dual biography in Malala: A Brave Girl from Pakistan/Iqbal: A Brave Boy from Pakistan (2014). As one of its covers aptly notes about this volume, it contains “Two stories of bravery in one beautiful book.” What is remarkable about these twinned stories is that readers can begin either narrative by flipping the volume upside down! Each begins on a separate side of the book, and each concludes as the stories “meet” in the wordless mid-point double spread. There, in a visually poetic rendering of the similar dreams of each child, Iqbal is shown on one page seeming to reach for a kite, while Malala is depicted on the other holding onto one as it soars. The dreamlike nature of this scene is heightened by its nighttime background, with stars dotting the dark sky. This sky unites the pages, as do the balanced composition of images and reuse of colors. Readers merely flip the book to bring the second scene into more prominent focus.

Award-winning author/illustrator Jeanette Winter has created an unusual as well as powerful dual biography in Malala: A Brave Girl from Pakistan/Iqbal: A Brave Boy from Pakistan (2014). As one of its covers aptly notes about this volume, it contains “Two stories of bravery in one beautiful book.” What is remarkable about these twinned stories is that readers can begin either narrative by flipping the volume upside down! Each begins on a separate side of the book, and each concludes as the stories “meet” in the wordless mid-point double spread. There, in a visually poetic rendering of the similar dreams of each child, Iqbal is shown on one page seeming to reach for a kite, while Malala is depicted on the other holding onto one as it soars. The dreamlike nature of this scene is heightened by its nighttime background, with stars dotting the dark sky. This sky unites the pages, as do the balanced composition of images and reuse of colors. Readers merely flip the book to bring the second scene into more prominent focus.

This book’s images display Winters’ signature style—vivid colors, flat perspective which removes the need for shading or shadows, and frequent use of decorative borders to frame scenes. She also depicts some sequential events in different sections of the same setting. That this so-called “folk art” style is also reminiscent of Persian miniature paintings is a further plus in this biography of two Muslim children, as it is in Winters’ related book about forbidden education for girls, Nasreen’s Secret School: A True Story from Afghanistan (2009). That multiple award-winning work shows both the devastating effects of repression by the Taliban regime there between 1996 and 2001 and the healing power of education.

This book’s images display Winters’ signature style—vivid colors, flat perspective which removes the need for shading or shadows, and frequent use of decorative borders to frame scenes. She also depicts some sequential events in different sections of the same setting. That this so-called “folk art” style is also reminiscent of Persian miniature paintings is a further plus in this biography of two Muslim children, as it is in Winters’ related book about forbidden education for girls, Nasreen’s Secret School: A True Story from Afghanistan (2009). That multiple award-winning work shows both the devastating effects of repression by the Taliban regime there between 1996 and 2001 and the healing power of education.  Illustrations here expand the text, as when Nasreen’s lost parents, shown holding hands, are depicted in the “blue sky beyond those dark clouds” that once obscured Nasreen’s inner as well as outer sight. It is also telling that Grandmother concludes this story with full-hearted piety, with the typical Muslim expression following an expressed hope, “Insha’ Allah” (God willing). Her pious wish, so unlike the Taliban’s limits on women’s education, is for Nasreen’s continued growth—that “soldiers can never close the windows that have opened for [her] granddaughter.” The centrality of this goal and this family connection is reinforced by Winters’ final image, showing us Grandmother and Nasreen close together, in the center of a framed yet boundless night sky.

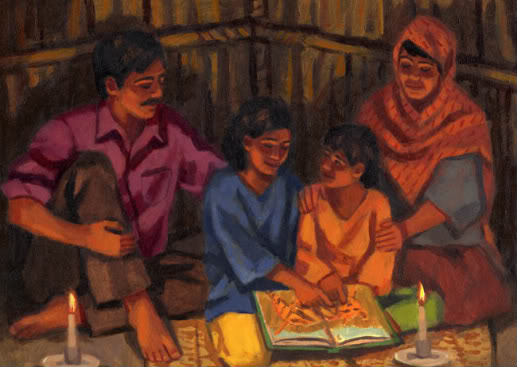

Illustrations here expand the text, as when Nasreen’s lost parents, shown holding hands, are depicted in the “blue sky beyond those dark clouds” that once obscured Nasreen’s inner as well as outer sight. It is also telling that Grandmother concludes this story with full-hearted piety, with the typical Muslim expression following an expressed hope, “Insha’ Allah” (God willing). Her pious wish, so unlike the Taliban’s limits on women’s education, is for Nasreen’s continued growth—that “soldiers can never close the windows that have opened for [her] granddaughter.” The centrality of this goal and this family connection is reinforced by Winters’ final image, showing us Grandmother and Nasreen close together, in the center of a framed yet boundless night sky. Yasmin’s Hammer (2010; 2015), written by Ann Malaspina and illustrated by Doug Chayka, is set in the country of Bangladesh, once known as East Pakistan. Its fictional account, rooted in real-life experiences, harkens back to Iqbal’s tale, as it is poverty that limits Yasmin’s access to education. Yasmin wants to know more to satisfy her curiosity and also to have job opportunities now far beyond her reach. Her family would like to send her to school, but they need the money that Yasmin, about 10 or 11 years old, and her younger sister Mita earn each day as brick chippers. This hot, dusty work leaves the girls with coughs that show how their lungs are being harmed, even as their bloodied and blistered fingers are the more apparent injuries.

Yasmin’s Hammer (2010; 2015), written by Ann Malaspina and illustrated by Doug Chayka, is set in the country of Bangladesh, once known as East Pakistan. Its fictional account, rooted in real-life experiences, harkens back to Iqbal’s tale, as it is poverty that limits Yasmin’s access to education. Yasmin wants to know more to satisfy her curiosity and also to have job opportunities now far beyond her reach. Her family would like to send her to school, but they need the money that Yasmin, about 10 or 11 years old, and her younger sister Mita earn each day as brick chippers. This hot, dusty work leaves the girls with coughs that show how their lungs are being harmed, even as their bloodied and blistered fingers are the more apparent injuries.  Yet the coins the girls bring home help pay for food and shelter, and will help their hard-working parents save enough money to purchase the rented rickshaw Father now pedals each day. ( Mother spends long hours washing clothes and cleaning houses.) Until then, it seems Yasmin must be content with the promised “Soon” she hears from her parents, a word she repeats to herself whenever school is mentioned.

Yet the coins the girls bring home help pay for food and shelter, and will help their hard-working parents save enough money to purchase the rented rickshaw Father now pedals each day. ( Mother spends long hours washing clothes and cleaning houses.) Until then, it seems Yasmin must be content with the promised “Soon” she hears from her parents, a word she repeats to herself whenever school is mentioned.  glowing candlelight, she and her family puzzle out what some of the words in this alphabet picture book might be. Her parents are moved by this experience. They increase their own heavy workloads, earning more money, so that Father can surprise Yasmin and Mita one morning with a rickshaw ride along an unknown route. The girls are not going to the brickyard to use their hammers. It is her father’s smile which helps Yasmine realize joyfully, as the book concludes, where they are instead headed: “Then I know. This is the way to school.”

glowing candlelight, she and her family puzzle out what some of the words in this alphabet picture book might be. Her parents are moved by this experience. They increase their own heavy workloads, earning more money, so that Father can surprise Yasmin and Mita one morning with a rickshaw ride along an unknown route. The girls are not going to the brickyard to use their hammers. It is her father’s smile which helps Yasmine realize joyfully, as the book concludes, where they are instead headed: “Then I know. This is the way to school.”  Young readers may also appreciate learning more about the history of child labor within the U.S. While the text of Russell Freedman’s award-winning Kids at Work: Lewis Hine and the Crusade Against Child Labor (1994; 1998) is best suited to upper elementary and older readers, Hines’ insightful photographs—still acting as change agents—will provoke interest and discussion in readers of all ages. Susan Campbell Bartoletti’s Kids on Strike (1999) is similarly illustrated with dramatic historical photos. And Lawrence Migdale’s sensitive photographs in Migrant

Young readers may also appreciate learning more about the history of child labor within the U.S. While the text of Russell Freedman’s award-winning Kids at Work: Lewis Hine and the Crusade Against Child Labor (1994; 1998) is best suited to upper elementary and older readers, Hines’ insightful photographs—still acting as change agents—will provoke interest and discussion in readers of all ages. Susan Campbell Bartoletti’s Kids on Strike (1999) is similarly illustrated with dramatic historical photos. And Lawrence Migdale’s sensitive photographs in Migrant  Worker: A Boy from the Rio Grande Valley (1996), written by Diane Hoyt-Goldsmith, demonstrate ways in which child labor still occurs in the contemporary United States. As youngsters experience the first days of this new school year, comparing their own recent photos—particularly ones taken at school—with ones in these books might be educational experiences in themselves.

Worker: A Boy from the Rio Grande Valley (1996), written by Diane Hoyt-Goldsmith, demonstrate ways in which child labor still occurs in the contemporary United States. As youngsters experience the first days of this new school year, comparing their own recent photos—particularly ones taken at school—with ones in these books might be educational experiences in themselves.  What sense do young U.S. readers, bombarded these days by the war of words between our presidential candidates and assaulted by the images and realities of U.S. gun violence, make of recent events in Turkey? A failed military takeover of the Turkish government on July 15 left hundreds dead and more than a thousand people injured, with thousands more later imprisoned, removed from their jobs, or forbidden to travel internationally. Just a few weeks before that, a deadly terrorist attack at Turkey’s largest airport, outside cosmopolitan Istanbul, shocked the world. I follow Turkish news not only because Turkey is an important U.S. ally but because our son lived in Istanbul for four years, from 2009 to 2013. We learned much about Turkey then and visited there, too.

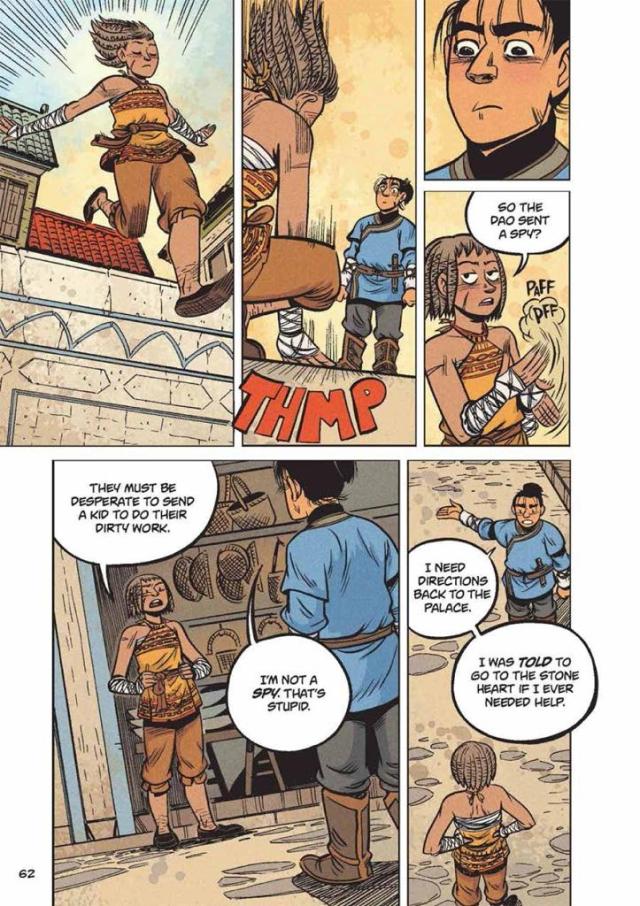

What sense do young U.S. readers, bombarded these days by the war of words between our presidential candidates and assaulted by the images and realities of U.S. gun violence, make of recent events in Turkey? A failed military takeover of the Turkish government on July 15 left hundreds dead and more than a thousand people injured, with thousands more later imprisoned, removed from their jobs, or forbidden to travel internationally. Just a few weeks before that, a deadly terrorist attack at Turkey’s largest airport, outside cosmopolitan Istanbul, shocked the world. I follow Turkish news not only because Turkey is an important U.S. ally but because our son lived in Istanbul for four years, from 2009 to 2013. We learned much about Turkey then and visited there, too.  I first caught up with author/illustrator Tony Cliff’s Delilah Dirk and the Turkish Lieutenant, a 2013 fiction bestseller, and its recently published sequel, Delilah Dirk and the King’s Shilling (2016). These swashbuckling adventures, set in the early 19th century when Great Britain was at war with Napoleonic France, feature the daring, sometimes law-breaking deeds of Delilah Dirk. In both books, this upper class British woman—whose incredible martial arts training, acrobatic skills, scientific gadgets, and penchant for violent “justice” remind me of superhero Batman—is accompanied by Mr. Erdemoglu Selim, the eponymous “Turkish lieutenant.” His is the voice of reason which only sometimes restrains Delilah, and his superior tea-making abilities and loyalty to the hot-headed woman who once saved his life both are important plot elements in several of their thrilling adventures.

I first caught up with author/illustrator Tony Cliff’s Delilah Dirk and the Turkish Lieutenant, a 2013 fiction bestseller, and its recently published sequel, Delilah Dirk and the King’s Shilling (2016). These swashbuckling adventures, set in the early 19th century when Great Britain was at war with Napoleonic France, feature the daring, sometimes law-breaking deeds of Delilah Dirk. In both books, this upper class British woman—whose incredible martial arts training, acrobatic skills, scientific gadgets, and penchant for violent “justice” remind me of superhero Batman—is accompanied by Mr. Erdemoglu Selim, the eponymous “Turkish lieutenant.” His is the voice of reason which only sometimes restrains Delilah, and his superior tea-making abilities and loyalty to the hot-headed woman who once saved his life both are important plot elements in several of their thrilling adventures.  While I was pleased to see author Cliff stress that friendship, rather than a stereotypical romance, unites this unconventional pair, I was disappointed to see how Turkey was used mainly as exotic background for the first novel. Constantinople (the earlier name for Istanbul) is that work’s first, riotously detailed setting. Selim is, at first, a lieutenant in the Ottoman Empire’s military. Yet the duo’s shipboard fights against the pirate captain Rakul, here set on the Bosphorus River and Sea of Marmara, might just as well have taken place on the Indian Ocean, with Mr. Selim being replaced by a native of the Indian sub-continent. Little that is unique to Turkish culture or politics ultimately figures in these volumes—a fact also re-emphasized by the biases of some British characters in the European setting of Delilah Dirk and the King’s Shilling. Its central villain, the treacherous Major Merrick, certainly disdains and lumps all dark-skinned people together, regardless of their country or continent of origin. Merrick’s views are ones that fueled British imperialism, though no background notes are given about that, the Ottoman Empire, or the Napoleonic Wars in either book. Perhaps—I am sad to realize—countries being at war need no explanation for some of today’s young readers, particularly ones seeking pleasure rather than information.

While I was pleased to see author Cliff stress that friendship, rather than a stereotypical romance, unites this unconventional pair, I was disappointed to see how Turkey was used mainly as exotic background for the first novel. Constantinople (the earlier name for Istanbul) is that work’s first, riotously detailed setting. Selim is, at first, a lieutenant in the Ottoman Empire’s military. Yet the duo’s shipboard fights against the pirate captain Rakul, here set on the Bosphorus River and Sea of Marmara, might just as well have taken place on the Indian Ocean, with Mr. Selim being replaced by a native of the Indian sub-continent. Little that is unique to Turkish culture or politics ultimately figures in these volumes—a fact also re-emphasized by the biases of some British characters in the European setting of Delilah Dirk and the King’s Shilling. Its central villain, the treacherous Major Merrick, certainly disdains and lumps all dark-skinned people together, regardless of their country or continent of origin. Merrick’s views are ones that fueled British imperialism, though no background notes are given about that, the Ottoman Empire, or the Napoleonic Wars in either book. Perhaps—I am sad to realize—countries being at war need no explanation for some of today’s young readers, particularly ones seeking pleasure rather than information.

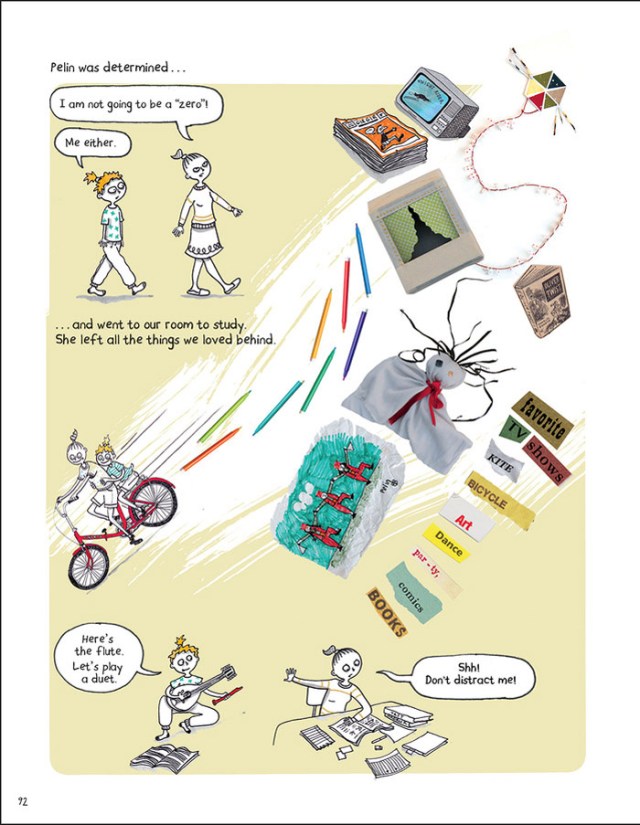

Similarly, the most dramatic events occurring in 1970s through 1990s Turkey take place mainly “offstage” in Ozge Samanci’s excellent graphic memoir, Dare to Disappoint: Growing Up in Turkey (2015). These dramas include war with Greece over Cyprus, coups, and attempted coups. Nonetheless, by selectively depicting her family’s daily life in the western coastal city of Izmir—including what she herself did not understand as a 6 year-old when the memoir begins—this author/illustrator has created a vividly intimate portrait of their lives, her growth as an individual, and how a restrictive society shaped individual choices and family dynamics. Sad to say, many of those repressive situations—government limits on mass communications; sudden arrest of people suspected of dissent, followed by torture or beatings; a military sometimes operating on its own; and government officials who “bend” laws to remain in power—still exist in Turkey today. As the backgrounds in some of Samanci’s illustrations slyly point out, through posters and graffiti on walls, only the names of some dissident groups have changed. I believe that reading this memoir will indeed help to inform tween and up readers about life in Turkey today, even though 21st century politics have brought new complications there. Yet Dare to Disappoint is anything but heavy-handed or heavy-hearted in its storytelling.

Similarly, the most dramatic events occurring in 1970s through 1990s Turkey take place mainly “offstage” in Ozge Samanci’s excellent graphic memoir, Dare to Disappoint: Growing Up in Turkey (2015). These dramas include war with Greece over Cyprus, coups, and attempted coups. Nonetheless, by selectively depicting her family’s daily life in the western coastal city of Izmir—including what she herself did not understand as a 6 year-old when the memoir begins—this author/illustrator has created a vividly intimate portrait of their lives, her growth as an individual, and how a restrictive society shaped individual choices and family dynamics. Sad to say, many of those repressive situations—government limits on mass communications; sudden arrest of people suspected of dissent, followed by torture or beatings; a military sometimes operating on its own; and government officials who “bend” laws to remain in power—still exist in Turkey today. As the backgrounds in some of Samanci’s illustrations slyly point out, through posters and graffiti on walls, only the names of some dissident groups have changed. I believe that reading this memoir will indeed help to inform tween and up readers about life in Turkey today, even though 21st century politics have brought new complications there. Yet Dare to Disappoint is anything but heavy-handed or heavy-hearted in its storytelling.

Ironically, to get a further sense of how suppressed groups live under a military regime, and how teens’ choices and friendships are constrained by the laws and customs upholding such regimes, readers might look past Turkey or any other clearly-identified country. Author/illustrator Faith Erin Hicks’ new graphic novel, The Nameless City (2016), colored by Jordie Bellaire, spotlights these questions in an adventure-filled, fantasy novel centered on two teens—a ruling caste young man named Kai and an impoverished, homeless young woman known only as Rat. Her people powerfully refuse to use the names given to their pre-industrial city by its succession of conquerors. That strategically-valuable city, located at a juncture on what might be the central Asian steppes, is prized by different ethnic groups, another distinction drawn here between conquerors and the conquered.

Ironically, to get a further sense of how suppressed groups live under a military regime, and how teens’ choices and friendships are constrained by the laws and customs upholding such regimes, readers might look past Turkey or any other clearly-identified country. Author/illustrator Faith Erin Hicks’ new graphic novel, The Nameless City (2016), colored by Jordie Bellaire, spotlights these questions in an adventure-filled, fantasy novel centered on two teens—a ruling caste young man named Kai and an impoverished, homeless young woman known only as Rat. Her people powerfully refuse to use the names given to their pre-industrial city by its succession of conquerors. That strategically-valuable city, located at a juncture on what might be the central Asian steppes, is prized by different ethnic groups, another distinction drawn here between conquerors and the conquered.

What would composer Aaron Copeland have made of the Jewish Film Festival in Bozeman, Montana, now in its second season? The Jewish, Brooklyn-born and raised Copeland (1900 – 1990) made notable use of his klezmer-infused, cityscape youth in many musical pieces, yet Copeland is probably best-known for musical works emblematic of the expansive American West. The Billy the Kid suite (1939), Rodeo (1942), and Appalachian Spring (1944)—all regularly performed by high school orchestras and aired on public radio stations—were created by the bar mitzvahed, agnostic son of Russian Jewish immigrants. Originally, their family name was Kaplan.

What would composer Aaron Copeland have made of the Jewish Film Festival in Bozeman, Montana, now in its second season? The Jewish, Brooklyn-born and raised Copeland (1900 – 1990) made notable use of his klezmer-infused, cityscape youth in many musical pieces, yet Copeland is probably best-known for musical works emblematic of the expansive American West. The Billy the Kid suite (1939), Rodeo (1942), and Appalachian Spring (1944)—all regularly performed by high school orchestras and aired on public radio stations—were created by the bar mitzvahed, agnostic son of Russian Jewish immigrants. Originally, their family name was Kaplan.  Copeland himself credited his early fascination with the pioneering American spirit to movies. He explained, “I suppose in one sense it’s a feat of the imagination . . . . But after all, a kid in Brooklyn would’ve seen movies with cowboys in them. . . . I did go out to the southwest fairly early in my career. And, I don’t know, every American kid grows up with a sense of cowboys and what the west must have been like.” Coming full circle, Copeland’s musical scores for films include one for a Western, The Red Pony (1948), based on a John Steinbeck story collection. (Copeland’s first, award-winning film score was for the movie version of another Steinbeck work, Of Mice and Men [1938], set in the ranch land of Depression-era California.)

Copeland himself credited his early fascination with the pioneering American spirit to movies. He explained, “I suppose in one sense it’s a feat of the imagination . . . . But after all, a kid in Brooklyn would’ve seen movies with cowboys in them. . . . I did go out to the southwest fairly early in my career. And, I don’t know, every American kid grows up with a sense of cowboys and what the west must have been like.” Coming full circle, Copeland’s musical scores for films include one for a Western, The Red Pony (1948), based on a John Steinbeck story collection. (Copeland’s first, award-winning film score was for the movie version of another Steinbeck work, Of Mice and Men [1938], set in the ranch land of Depression-era California.)  What feats our imaginations can indeed accomplish! As a tween, I loved singer Gene Pitney’s crooning of that movie’s title song so much, played a 45 RPM record of it so often, that I always hear Pitney’s lush voice over the film credits—even though the Pitney version was not released until weeks after the movie’s debut. I guess Gene Pitney is part of my Brooklyn-bred, city kid’s dream of the American West.

What feats our imaginations can indeed accomplish! As a tween, I loved singer Gene Pitney’s crooning of that movie’s title song so much, played a 45 RPM record of it so often, that I always hear Pitney’s lush voice over the film credits—even though the Pitney version was not released until weeks after the movie’s debut. I guess Gene Pitney is part of my Brooklyn-bred, city kid’s dream of the American West. Now that I too have visited Bozeman, walking its friendly streets and viewing the magnificent vistas of the aptly-named Big Sky state, I appreciate Copeland’s musical renditions of the West—ebullient, witty, solemn, grand—even more. He really got so much of it so right! Yet the West Copeland dreamed about and created really never contained just one melody, and nowadays it contains many more. There is a Jewish Film Festival now in Bozeman, with wailing klezmer clarinets somewhere in the air. And before that, there were Jewish merchants in Montana as early as the 1870s, with a synagogue established in Helena in 1890.

Now that I too have visited Bozeman, walking its friendly streets and viewing the magnificent vistas of the aptly-named Big Sky state, I appreciate Copeland’s musical renditions of the West—ebullient, witty, solemn, grand—even more. He really got so much of it so right! Yet the West Copeland dreamed about and created really never contained just one melody, and nowadays it contains many more. There is a Jewish Film Festival now in Bozeman, with wailing klezmer clarinets somewhere in the air. And before that, there were Jewish merchants in Montana as early as the 1870s, with a synagogue established in Helena in 1890. Sometimes reality is better, richer, and more complicated than one’s dreams—worth the extra effort to discover and explore. Sometimes, though, dreams may turn out to be dismaying or disappointing. I was delighted a few years ago when the Western Writers of America considered a biography I had written about a 19th century Northern Paiute leader —Sarah Winnemucca: Scout, Activist, and Teacher (2006)—for one of its prestigious Spur Awards. I felt a little like Aaron Copeland back then, in my own much smaller way another Brooklyn-born kid imaginatively taking part in and recreating the Old West.

Sometimes reality is better, richer, and more complicated than one’s dreams—worth the extra effort to discover and explore. Sometimes, though, dreams may turn out to be dismaying or disappointing. I was delighted a few years ago when the Western Writers of America considered a biography I had written about a 19th century Northern Paiute leader —Sarah Winnemucca: Scout, Activist, and Teacher (2006)—for one of its prestigious Spur Awards. I felt a little like Aaron Copeland back then, in my own much smaller way another Brooklyn-born kid imaginatively taking part in and recreating the Old West.  as much. Each Golden Spur Award is an actual, three-dimensional gilt spur mounted on a similar wall plaque—a reality I could never have appreciated without a wry smile and shake of the head. I admit to my limited experience and world view here, which make spurs still the stuff of other people’s lives, of history and the movies. For me, some connections between Brooklyn and Bozeman still remain best left to the imagination. . . unless and until Daniel shares other global airs now current in Bozeman, ones following Aaron Copeland’s dream.

as much. Each Golden Spur Award is an actual, three-dimensional gilt spur mounted on a similar wall plaque—a reality I could never have appreciated without a wry smile and shake of the head. I admit to my limited experience and world view here, which make spurs still the stuff of other people’s lives, of history and the movies. For me, some connections between Brooklyn and Bozeman still remain best left to the imagination. . . unless and until Daniel shares other global airs now current in Bozeman, ones following Aaron Copeland’s dream. A health crisis recently overtook our family, with my son Daniel suddenly in the hospital a long way from our home. Now that his health is more stable, the problem being addressed, I find myself thinking about those questions and bits of wisdom that often seem distant from daily life. The whys and hows of existence. The truths underlying old clichés such as “Take time to smell the roses.” The reasons we have rituals to mark special occasions and milestone events. Aptly, I already had a copy of author/illustrator Lucy Knisley’s brand-new memoir about her own special occasion, Something New: Tales from a Makeshift Bride (2016), at home. The charms of this comforting, entertaining memoir led me to catch up with Knisley’s earlier, award-winning memoir, Relish: My Life in the Kitchen (2013). Her focused, lighthearted take there on two pleasurable daily activities sometimes overlooked in life’s bustle—eating and cooking—was just the tonic I needed. (Although, of course, a wedding of some sort may someday figure in my adult son’s future. No pressure there, son. All in your own good, long lifetime.)

A health crisis recently overtook our family, with my son Daniel suddenly in the hospital a long way from our home. Now that his health is more stable, the problem being addressed, I find myself thinking about those questions and bits of wisdom that often seem distant from daily life. The whys and hows of existence. The truths underlying old clichés such as “Take time to smell the roses.” The reasons we have rituals to mark special occasions and milestone events. Aptly, I already had a copy of author/illustrator Lucy Knisley’s brand-new memoir about her own special occasion, Something New: Tales from a Makeshift Bride (2016), at home. The charms of this comforting, entertaining memoir led me to catch up with Knisley’s earlier, award-winning memoir, Relish: My Life in the Kitchen (2013). Her focused, lighthearted take there on two pleasurable daily activities sometimes overlooked in life’s bustle—eating and cooking—was just the tonic I needed. (Although, of course, a wedding of some sort may someday figure in my adult son’s future. No pressure there, son. All in your own good, long lifetime.)  depicts these events plus the following year, when Knisley’s whole family (including her retired caterer mother) became involved in planning and hosting her large do-it-yourself (DIY) wedding. Her memoir is a satirical critique of the Western wedding industry, a humorous look at strange wedding traditions world-wide, and a wry, self-mocking expose of how Knisley’s obsessive involvement with fine, locavore cuisine and handicrafts took over her life during that wedding-planning year. Along the way, she continues the exploration, begun in Relish, of her close relationship with her free-spirit mother, with whom she lived after her parents’ divorce.

depicts these events plus the following year, when Knisley’s whole family (including her retired caterer mother) became involved in planning and hosting her large do-it-yourself (DIY) wedding. Her memoir is a satirical critique of the Western wedding industry, a humorous look at strange wedding traditions world-wide, and a wry, self-mocking expose of how Knisley’s obsessive involvement with fine, locavore cuisine and handicrafts took over her life during that wedding-planning year. Along the way, she continues the exploration, begun in Relish, of her close relationship with her free-spirit mother, with whom she lived after her parents’ divorce.  shows sad-faced Lucy hugging her cat, with the word “GLOOM” in thin mauve letters dominating the rest of the panel. Throughout this work, the author/illustrator also cleverly uses photographs and photo-montages to both illustrate and comment on events. These include entire pages filled with cut-out magazine photos of brides and montages of actual wedding invitations Knisley had accumulated. I looked forward to these “real-life” pictures of the characters, places, and related items in this memoir—and you will too!

shows sad-faced Lucy hugging her cat, with the word “GLOOM” in thin mauve letters dominating the rest of the panel. Throughout this work, the author/illustrator also cleverly uses photographs and photo-montages to both illustrate and comment on events. These include entire pages filled with cut-out magazine photos of brides and montages of actual wedding invitations Knisley had accumulated. I looked forward to these “real-life” pictures of the characters, places, and related items in this memoir—and you will too!

Relish: My Life in the Kitchen (2013) follows Knisley from infancy, “a child raised by foodies” in New York City and later in upstate New York, through her college years. This memoir is infused with Knisley’s belief that her most “vivid memories jog [her] brain with the recollection of how things tasted.” These “taste-memories” are introduced early on, depicted as colorful, wordless balloons by the creative author/illustrator. Later, instead of the interspersed photographs found in Something New, Knisley interweaves sprightly cooking directions and recipes for some of her favorite foods and dishes. Readers will, for instance, learn how to best prepare mushrooms as well as how to cook huevos rancheros and sushi rolls.

Relish: My Life in the Kitchen (2013) follows Knisley from infancy, “a child raised by foodies” in New York City and later in upstate New York, through her college years. This memoir is infused with Knisley’s belief that her most “vivid memories jog [her] brain with the recollection of how things tasted.” These “taste-memories” are introduced early on, depicted as colorful, wordless balloons by the creative author/illustrator. Later, instead of the interspersed photographs found in Something New, Knisley interweaves sprightly cooking directions and recipes for some of her favorite foods and dishes. Readers will, for instance, learn how to best prepare mushrooms as well as how to cook huevos rancheros and sushi rolls.

I am happy that my son already acts on similar beliefs. (A bit of a “foodie” himself, Daniel enjoys cooking, and last year we re-bonded over the pleasures of a new immersion blender.) I think Daniel’s appetite for life will sustain him as he faces medical adversity with the same empathy and gusto that have led him to travel the globe, tasting food and “tasting” cultures that most of us Westerners will never encounter. So many great meals, new places and people, and wonderful books ahead of him! Now added to my own pile of to-be-reads: Lucy Knisley’s autobiographical travelogues French Milk (2007), An Age of License (2014), and Displacement (2015).

I am happy that my son already acts on similar beliefs. (A bit of a “foodie” himself, Daniel enjoys cooking, and last year we re-bonded over the pleasures of a new immersion blender.) I think Daniel’s appetite for life will sustain him as he faces medical adversity with the same empathy and gusto that have led him to travel the globe, tasting food and “tasting” cultures that most of us Westerners will never encounter. So many great meals, new places and people, and wonderful books ahead of him! Now added to my own pile of to-be-reads: Lucy Knisley’s autobiographical travelogues French Milk (2007), An Age of License (2014), and Displacement (2015).  Now that it is summer vacation time in North America, more of our young people’s teachable moments will take place outside of school. Graphic works can play a part in the lessons they learn—especially in areas often given shorter shrift in today’s STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) focused curriculum. Today I look at two recently-published graphic works which will entertain and instruct a range of school-weary readers. These books focus on life lessons that extend beyond the classroom—and impart this wisdom in creative ways both old and new.

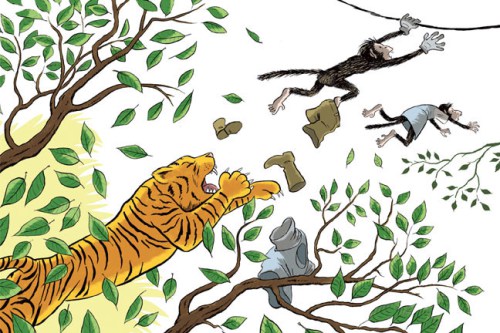

Now that it is summer vacation time in North America, more of our young people’s teachable moments will take place outside of school. Graphic works can play a part in the lessons they learn—especially in areas often given shorter shrift in today’s STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) focused curriculum. Today I look at two recently-published graphic works which will entertain and instruct a range of school-weary readers. These books focus on life lessons that extend beyond the classroom—and impart this wisdom in creative ways both old and new. Veteran author/illustrator James Sturm has given us Birdsong: A Story in Pictures (2016). Sturm’s end notes link this wordless book to the Japanese storytelling tradition of kamishibai, which once delighted children throughout Japan. (Kamishibai is the focus of my March, 2014 Gone Graphic and is also mentioned in the June, 2014 and June, 2015 posts.) While Birdsong is being marketed by publisher Toon Books for early readers, appropriate for grades K -1, I agree with the reviewer who felt its wordless pages have “an almost universal appeal,” not limited to any age range.

Veteran author/illustrator James Sturm has given us Birdsong: A Story in Pictures (2016). Sturm’s end notes link this wordless book to the Japanese storytelling tradition of kamishibai, which once delighted children throughout Japan. (Kamishibai is the focus of my March, 2014 Gone Graphic and is also mentioned in the June, 2014 and June, 2015 posts.) While Birdsong is being marketed by publisher Toon Books for early readers, appropriate for grades K -1, I agree with the reviewer who felt its wordless pages have “an almost universal appeal,” not limited to any age range.  Empathy and kindness are taught in Birdsong, which shows cruel children who are magically transformed into monkeys. Captured and then themselves put on heartless display, the unhappy young simians with help escape to the countryside. There, with their new awareness, they show kindness and generosity towards the turtles and birds they once tormented. Birdsong’s full-color pages also encourage imaginative thought and storytelling skills, as each left-hand page is left blank, save for a decorative side border. Readers can and will be inspired to “fill in” these blanks, with their own versions of who the magician is who transforms the children, how they are captured, and what leads one captor to free them. Imaginations will also be fueled by thoughts about what kinds of lives and adventures the pair will now have. Will they remain monkeys, or will they ever again be human?

Empathy and kindness are taught in Birdsong, which shows cruel children who are magically transformed into monkeys. Captured and then themselves put on heartless display, the unhappy young simians with help escape to the countryside. There, with their new awareness, they show kindness and generosity towards the turtles and birds they once tormented. Birdsong’s full-color pages also encourage imaginative thought and storytelling skills, as each left-hand page is left blank, save for a decorative side border. Readers can and will be inspired to “fill in” these blanks, with their own versions of who the magician is who transforms the children, how they are captured, and what leads one captor to free them. Imaginations will also be fueled by thoughts about what kinds of lives and adventures the pair will now have. Will they remain monkeys, or will they ever again be human?  Also, readers could be asked when this story takes place. How modern, ancient, or perhaps timeless is its setting? The child protagonists could be wearing medieval play costumes and the magician could be a modern hermit dressed in ragged clothes . . . . The carnival barker might be wearing an old-fashioned, 19th century barker’s bow tie and hat, while the audience could be wearing unfashionable clothes or garments that are up-to-date with mid-twentieth century styles. Geographically, Birdsong’s landscapes might be Western . . . but they could also be Asian, too. The wildlife Sturm selects—a tiger and those monkeys—enhances the mysteries there. Furthermore, while the children, carnival barker, and some audience members are Caucasian, the side-show audience is multi-racial and the magician’s angry features leave some doubt about his ethnicity. Tellingly, the one facial close-up Sturm draws—still using the minimal, semi-realistic style for which he is known—is of the two imprisoned, sad monkeys, their eyes glistening . . . perhaps with unshed tears.

Also, readers could be asked when this story takes place. How modern, ancient, or perhaps timeless is its setting? The child protagonists could be wearing medieval play costumes and the magician could be a modern hermit dressed in ragged clothes . . . . The carnival barker might be wearing an old-fashioned, 19th century barker’s bow tie and hat, while the audience could be wearing unfashionable clothes or garments that are up-to-date with mid-twentieth century styles. Geographically, Birdsong’s landscapes might be Western . . . but they could also be Asian, too. The wildlife Sturm selects—a tiger and those monkeys—enhances the mysteries there. Furthermore, while the children, carnival barker, and some audience members are Caucasian, the side-show audience is multi-racial and the magician’s angry features leave some doubt about his ethnicity. Tellingly, the one facial close-up Sturm draws—still using the minimal, semi-realistic style for which he is known—is of the two imprisoned, sad monkeys, their eyes glistening . . . perhaps with unshed tears. Limiting each page to one image makes Birdsong accessible to even pre-readers, but its appeal is definitely more widespread—not only to multi-age readers but also

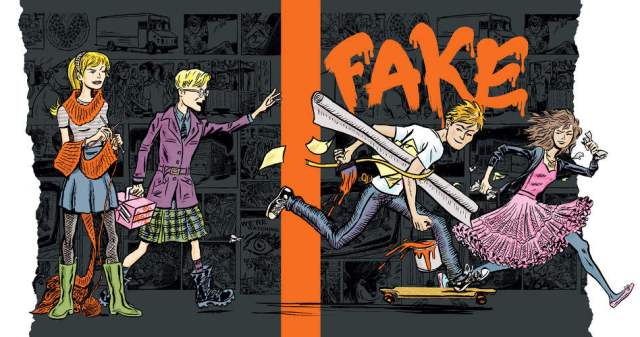

Limiting each page to one image makes Birdsong accessible to even pre-readers, but its appeal is definitely more widespread—not only to multi-age readers but also  The relationships between performance, art, and community are key plot elements in the fast-paced, frequently-funny Original Fake (2016), written by award-winner Kirstin Cronn-Mills and illustrated by E. Eero Johnson. Its narrator, high school junior Frankie Neuman, is a visual artist who feels unappreciated in his family of extroverted dancers and singers. When Frankie gets involved in law-breaking “performance art,” helping a world-renowned artistic prankster leave satirical, often scurrilous art pieces in public places, Frankie finally feels powerful and successful. An extra ego boost is the attention paid to his own anonymous public art works—pieces designed to erode the social standing of his self-centered sister Lou. But how unhappy does that younger teen deserve to be? What kind of relationship does Frankie really want to have with her? And what will his relationship with his exuberant parents be, now that their quiet son is mysteriously staying out all night, disobeying rules and being questioned by the police?

The relationships between performance, art, and community are key plot elements in the fast-paced, frequently-funny Original Fake (2016), written by award-winner Kirstin Cronn-Mills and illustrated by E. Eero Johnson. Its narrator, high school junior Frankie Neuman, is a visual artist who feels unappreciated in his family of extroverted dancers and singers. When Frankie gets involved in law-breaking “performance art,” helping a world-renowned artistic prankster leave satirical, often scurrilous art pieces in public places, Frankie finally feels powerful and successful. An extra ego boost is the attention paid to his own anonymous public art works—pieces designed to erode the social standing of his self-centered sister Lou. But how unhappy does that younger teen deserve to be? What kind of relationship does Frankie really want to have with her? And what will his relationship with his exuberant parents be, now that their quiet son is mysteriously staying out all night, disobeying rules and being questioned by the police?

Original Fake is part of a new trend—the hybrid novel, part text and part graphic novel. (The February, 2014 Gone Graphic focused on this trend.) Some of Original Fake’s graphic pages illustrate the text, while others take the place of traditional prose. Near the work’s conclusion, seven graphic pages effectively convey Frankie’s surreal dream, as he works through his thoughts and emotions, both painful and painfully funny. The book’s happy conclusion is also presented in a color-saturated image, accompanied by words seemingly painted in bold brushstrokes.

Original Fake is part of a new trend—the hybrid novel, part text and part graphic novel. (The February, 2014 Gone Graphic focused on this trend.) Some of Original Fake’s graphic pages illustrate the text, while others take the place of traditional prose. Near the work’s conclusion, seven graphic pages effectively convey Frankie’s surreal dream, as he works through his thoughts and emotions, both painful and painfully funny. The book’s happy conclusion is also presented in a color-saturated image, accompanied by words seemingly painted in bold brushstrokes.  Unlike Birdsong, set in the nonspecific countryside, Original Fake has a very specific urban location—mine! Minneapolis, its suburbs, and landmarks are named as well as detailed by Mankato-dweller Cronn-Mills and Minneapolitan Johnson. It is lots of fun to read about such familiar streets and sights. One way to select some summer reading might be to look for books set in your own community, state, or region. As performance artists—

Unlike Birdsong, set in the nonspecific countryside, Original Fake has a very specific urban location—mine! Minneapolis, its suburbs, and landmarks are named as well as detailed by Mankato-dweller Cronn-Mills and Minneapolitan Johnson. It is lots of fun to read about such familiar streets and sights. One way to select some summer reading might be to look for books set in your own community, state, or region. As performance artists— For a few days in spring, before cable TV and streaming media, actor Charlton Heston once dominated North America’s television airwaves. Sometimes on the same weekend, Heston’s rugged features and sonorous voice would bring Biblical times to life at Passover and Easter. Network TV always broadcast The Ten Commandments (1956) and Ben Hur (1959), both starring the Midwestern actor. For generations of viewers, Heston embodied Moses and noble Ben Hur, whose epic path intersects that of Jesus. As I sit here munching leftover Passover matzoh, I am reminded of those reverent, stirring films—and the ways in which today’s popular culture, including graphic novels, has expanded and shifted awareness of Biblical icons.

For a few days in spring, before cable TV and streaming media, actor Charlton Heston once dominated North America’s television airwaves. Sometimes on the same weekend, Heston’s rugged features and sonorous voice would bring Biblical times to life at Passover and Easter. Network TV always broadcast The Ten Commandments (1956) and Ben Hur (1959), both starring the Midwestern actor. For generations of viewers, Heston embodied Moses and noble Ben Hur, whose epic path intersects that of Jesus. As I sit here munching leftover Passover matzoh, I am reminded of those reverent, stirring films—and the ways in which today’s popular culture, including graphic novels, has expanded and shifted awareness of Biblical icons.  Nowadays we have ready access to many more films—including silent versions and remakes of those Heston classics. Mainstream movie retellings of the Old and New Testament generally are as reverent as those 1950s award-winners and their ilk were. World cinema has also given us access to classic retellings of religious traditions outside the Judeo-Christian one. Many graphic versions of religious narratives have also been created—and used successfully—to communicate and teach their views to youngsters and non-believers. Yet other graphic novels in this genre function in a different way—to question and comment on their stories, to examine and explore other ways of interpreting these Biblical tales. They are akin to some homespun homilies or what is within Judaism an ancient tradition of written interpretation known as midrash. Today, I look at two graphic novels which raise new questions—and answer some personal ones, for me—about Biblical icons from my own youth: Moses and David.