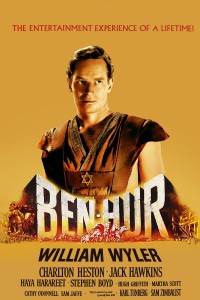

For a few days in spring, before cable TV and streaming media, actor Charlton Heston once dominated North America’s television airwaves. Sometimes on the same weekend, Heston’s rugged features and sonorous voice would bring Biblical times to life at Passover and Easter. Network TV always broadcast The Ten Commandments (1956) and Ben Hur (1959), both starring the Midwestern actor. For generations of viewers, Heston embodied Moses and noble Ben Hur, whose epic path intersects that of Jesus. As I sit here munching leftover Passover matzoh, I am reminded of those reverent, stirring films—and the ways in which today’s popular culture, including graphic novels, has expanded and shifted awareness of Biblical icons.

For a few days in spring, before cable TV and streaming media, actor Charlton Heston once dominated North America’s television airwaves. Sometimes on the same weekend, Heston’s rugged features and sonorous voice would bring Biblical times to life at Passover and Easter. Network TV always broadcast The Ten Commandments (1956) and Ben Hur (1959), both starring the Midwestern actor. For generations of viewers, Heston embodied Moses and noble Ben Hur, whose epic path intersects that of Jesus. As I sit here munching leftover Passover matzoh, I am reminded of those reverent, stirring films—and the ways in which today’s popular culture, including graphic novels, has expanded and shifted awareness of Biblical icons.

Nowadays we have ready access to many more films—including silent versions and remakes of those Heston classics. Mainstream movie retellings of the Old and New Testament generally are as reverent as those 1950s award-winners and their ilk were. World cinema has also given us access to classic retellings of religious traditions outside the Judeo-Christian one. Many graphic versions of religious narratives have also been created—and used successfully—to communicate and teach their views to youngsters and non-believers. Yet other graphic novels in this genre function in a different way—to question and comment on their stories, to examine and explore other ways of interpreting these Biblical tales. They are akin to some homespun homilies or what is within Judaism an ancient tradition of written interpretation known as midrash. Today, I look at two graphic novels which raise new questions—and answer some personal ones, for me—about Biblical icons from my own youth: Moses and David.

Nowadays we have ready access to many more films—including silent versions and remakes of those Heston classics. Mainstream movie retellings of the Old and New Testament generally are as reverent as those 1950s award-winners and their ilk were. World cinema has also given us access to classic retellings of religious traditions outside the Judeo-Christian one. Many graphic versions of religious narratives have also been created—and used successfully—to communicate and teach their views to youngsters and non-believers. Yet other graphic novels in this genre function in a different way—to question and comment on their stories, to examine and explore other ways of interpreting these Biblical tales. They are akin to some homespun homilies or what is within Judaism an ancient tradition of written interpretation known as midrash. Today, I look at two graphic novels which raise new questions—and answer some personal ones, for me—about Biblical icons from my own youth: Moses and David.

I always wondered about the ten plagues visited upon the Egyptians at Moses’ command. Did he or stubborn pharaoh Ramses feel any guilt or regret at the torments inflicted upon Egypt’s people, land, and creatures, until Ramses finally heeds God’s injunction about the Israelites: “Let my people go!”? The Jewish Passover tradition of naming these plagues during the holiday’s two ritual meals or seders is, we are told, the way we acknowledge that ancient suffering, taking no pleasure in it. But what was it like to incite and experience blood, frogs, insects, wild animals, animal death, boils, hail, locusts, darkness, and—worst of all—death of the firstborn? Had Charlton Heston and director Cecil B. DeMille really gotten it right?

The graphic novel The Lone and Level Sands (2005), written by A. David Lewis and illustrated by mpMann, with colors by Jennifer Rodgers, suggests how much better that Hollywood epic might have been. As Lewis notes in his Introduction, his book was designed to fill “the most gaps” in the book of Exodus—particularly “in the human reactions of Ramses, Moses, and their respective people.” Its main character is Ramses, rather than Moses, as Lewis reimagines Ramses’ life not only through its Biblical account but through the multiple lenses of Islam’s Koran, poet Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ozymandias,” and—yes—director DeMille’s widescreen, Technicolor film.

The graphic novel The Lone and Level Sands (2005), written by A. David Lewis and illustrated by mpMann, with colors by Jennifer Rodgers, suggests how much better that Hollywood epic might have been. As Lewis notes in his Introduction, his book was designed to fill “the most gaps” in the book of Exodus—particularly “in the human reactions of Ramses, Moses, and their respective people.” Its main character is Ramses, rather than Moses, as Lewis reimagines Ramses’ life not only through its Biblical account but through the multiple lenses of Islam’s Koran, poet Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ozymandias,” and—yes—director DeMille’s widescreen, Technicolor film.

Words and images deftly give us moving details about Ramses the man and family member. We learn that Ramses’ father once called him by the nickname that the grown pharaoh later affectionately used for his own, now-adult son—“little apricot.” And it is Moses’ knowledge of this old family nickname that convinces Ramses that this bearded stranger really is the adopted cousin he has  not seen in forty years! In addition to eloquent, formal court pronouncements, Lewis’ characters also speak awkwardly or hesitantly when overcome by emotion or sickness. Leaving his mysteriously, frighteningly ill wife, Ramses stutters, “. . . I . . . I will return soon, beloved . . . “ Larger, bolder print conveys sound effects and startled utterances, such as musing Ramses’ “GAH!” when an arrow—with a resounding “SCHHHWOKK!!!”—pins a plague frog to the wall behind him. We see and hear Ramses make and break promises to release the Israelites, as a seemingly supernatural force, speaking through his relatives and advisors, urges him to renege. In Lewis’ fleshed-out version of Exodus, the Egyptians are in this way always doomed to pay for their misdeeds. As Ramses laments over the lifeless body of his wife, “—What cruel author assigns us to this fate?”

not seen in forty years! In addition to eloquent, formal court pronouncements, Lewis’ characters also speak awkwardly or hesitantly when overcome by emotion or sickness. Leaving his mysteriously, frighteningly ill wife, Ramses stutters, “. . . I . . . I will return soon, beloved . . . “ Larger, bolder print conveys sound effects and startled utterances, such as musing Ramses’ “GAH!” when an arrow—with a resounding “SCHHHWOKK!!!”—pins a plague frog to the wall behind him. We see and hear Ramses make and break promises to release the Israelites, as a seemingly supernatural force, speaking through his relatives and advisors, urges him to renege. In Lewis’ fleshed-out version of Exodus, the Egyptians are in this way always doomed to pay for their misdeeds. As Ramses laments over the lifeless body of his wife, “—What cruel author assigns us to this fate?”

The Lone and Level Sands also contains scenes which have us overhearing the interactions of brothers Moses and Aaron, as each leader sometimes doubts himself or his brother. We even hear their sister Miriam’s annoyance with prophet Moses’ characterization of God as male: “Hmmp. “’His,’ eh, Moses.” followed by what seems to be his standard reply, “<Sigh>. It matters not, Miriam. . . “ That Miriam and this exchange are placed literally at the periphery of the page reinforces how marginal her concerns are to the main characters here. Along with fleshing out central characters in the book of Exodus, Lewis also offers comments from minor Egyptian priests and palace guards and from unnamed, individual Israelites, as they suffer slavery and anticipate their escape.

The Lone and Level Sands also contains scenes which have us overhearing the interactions of brothers Moses and Aaron, as each leader sometimes doubts himself or his brother. We even hear their sister Miriam’s annoyance with prophet Moses’ characterization of God as male: “Hmmp. “’His,’ eh, Moses.” followed by what seems to be his standard reply, “<Sigh>. It matters not, Miriam. . . “ That Miriam and this exchange are placed literally at the periphery of the page reinforces how marginal her concerns are to the main characters here. Along with fleshing out central characters in the book of Exodus, Lewis also offers comments from minor Egyptian priests and palace guards and from unnamed, individual Israelites, as they suffer slavery and anticipate their escape.

Illustrator mpMann does a great job of highlighting the experiences of central characters and filling in events. Close-ups of distraught faces alternate with more distant views in panels of different sizes and shapes, and emotional reactions are sometimes conveyed by inserting a reaction shot panel into the distressing scene. Word balloons extend outside panels to unite events, while we sometimes view events from an overhead or lower perspective as well as straight on. Some strongly emotional events are drawn without frames. One particularly notable example of this is the double page spread in which readers see Egyptians lamenting the “animal death” that plagues even their guarded or hidden animals, and which even extends to the rotting of just-slaughtered meat. Bold, thick lines reinforce the intense dramas being enacted throughout the novel. Many illustrations use the color black densely enough to resemble the chiaroscuro of wood cut prints. The plague of darkness is, as well, conveyed appropriately by all black panels, in which only the white words of dismayed, frightened characters appear.

Illustrator mpMann does a great job of highlighting the experiences of central characters and filling in events. Close-ups of distraught faces alternate with more distant views in panels of different sizes and shapes, and emotional reactions are sometimes conveyed by inserting a reaction shot panel into the distressing scene. Word balloons extend outside panels to unite events, while we sometimes view events from an overhead or lower perspective as well as straight on. Some strongly emotional events are drawn without frames. One particularly notable example of this is the double page spread in which readers see Egyptians lamenting the “animal death” that plagues even their guarded or hidden animals, and which even extends to the rotting of just-slaughtered meat. Bold, thick lines reinforce the intense dramas being enacted throughout the novel. Many illustrations use the color black densely enough to resemble the chiaroscuro of wood cut prints. The plague of darkness is, as well, conveyed appropriately by all black panels, in which only the white words of dismayed, frightened characters appear.

Colorist Jennifer Rodgers cues readers to shifts in tone with different, appropriate color palettes. Moses’ supernatural transformation of staffs into snakes is awash in eerie green, while nighttime events are frequently signaled by cool purple as well as black. Violence and anger are backgrounded by reddish-orange. Although The Lone and Level Sands was originally self-published in black and white, Rodgers’ work here is a strong, seamless addition to the overall success of this powerful book. Readers tween and up will do well with the formal court language that is interspersed throughout the novel.

Colorist Jennifer Rodgers cues readers to shifts in tone with different, appropriate color palettes. Moses’ supernatural transformation of staffs into snakes is awash in eerie green, while nighttime events are frequently signaled by cool purple as well as black. Violence and anger are backgrounded by reddish-orange. Although The Lone and Level Sands was originally self-published in black and white, Rodgers’ work here is a strong, seamless addition to the overall success of this powerful book. Readers tween and up will do well with the formal court language that is interspersed throughout the novel.

The simple language in author/illustrator Tom Gauld’s  Goliath (2012), though, makes it accessible for even younger readers. Ironically, it is older readers—ones already accustomed to the traditional Bible story of giant warrior Goliath’s defeat by the slingshot-wielding shepherd boy David—who may be disconcerted by Gauld’s version of this encounter. He totally up-ends our expectations, giving new life to the Gershwin brothers’ irreverent song about the Bible, “It Ain’t Necessarily So.” Here, the bold victory that supposedly sets David on the path to anointed kinghood is shown to be mere happenstance—and a false triumph to boot.

Goliath (2012), though, makes it accessible for even younger readers. Ironically, it is older readers—ones already accustomed to the traditional Bible story of giant warrior Goliath’s defeat by the slingshot-wielding shepherd boy David—who may be disconcerted by Gauld’s version of this encounter. He totally up-ends our expectations, giving new life to the Gershwin brothers’ irreverent song about the Bible, “It Ain’t Necessarily So.” Here, the bold victory that supposedly sets David on the path to anointed kinghood is shown to be mere happenstance—and a false triumph to boot.

After using Biblical phrases to introduce the war between the Philistines and Israelites, Gauld presents solitary Goliath in a series of wordless  pages. This Philistine’s evening routines are calm, harmless ones, as the cartoon-like figure, drawn with only a hint of features and no apparent musculature, is shown far apart from his army camp. This Goliath is a mild-mannered clerk rather than a fierce warrior! He is too meek to protest effectively when an army bureaucrat has the bright idea of encasing huge Goliath in armor and then positioning him to challenge and perhaps frighten the Israelites into surrender. Goliath is as trapped by expectations of him as is the bear chained up by the Philistines. That animal is forced to defend itself in fights that Goliath is too tenderhearted to watch. Humorous elements, such as bits of Goliath’s armor continuing to drop off, make witnessing his discomfort both more bearable and somehow dismaying. As in The Lone and Level Sands, we know how this story ends.

pages. This Philistine’s evening routines are calm, harmless ones, as the cartoon-like figure, drawn with only a hint of features and no apparent musculature, is shown far apart from his army camp. This Goliath is a mild-mannered clerk rather than a fierce warrior! He is too meek to protest effectively when an army bureaucrat has the bright idea of encasing huge Goliath in armor and then positioning him to challenge and perhaps frighten the Israelites into surrender. Goliath is as trapped by expectations of him as is the bear chained up by the Philistines. That animal is forced to defend itself in fights that Goliath is too tenderhearted to watch. Humorous elements, such as bits of Goliath’s armor continuing to drop off, make witnessing his discomfort both more bearable and somehow dismaying. As in The Lone and Level Sands, we know how this story ends.

A limited color palette of grey tones, sepia, and white reflects the quiet and monotony of Goliath’s days, with only a doddering wanderer and a young shield bearer for company. This boy’s repetition of gossip about “fierce” Goliath, his strength and mighty deeds, is so far from the truth as to be funny. When Goliath sees that the bear has escaped, he begins to have thoughts about new possibilities for himself. Yet he waits just one day too long to put his escape plans into action. We with Goliath hear the Biblical phrases with which David approaches, proclaiming his intent to slay the giant, before we see him. And then—horrifyingly—we see centered on one full-page panel a rock . . . just a rock. We know even before turning the page that this is the ordinary stone that will doom Goliath. The “Thunk” that accompanies the stone’s hitting Goliath’s forehead is a stark contrast to the rolling, majestic Biblical phrases that accompany the following panels, where “victorious” David cuts off the giant’s head and takes it off in a sack to secure his destined future as a hero and, eventually, a worthy king. Rather than satisfaction at the end of this Biblical incident, we feel dismay. At this point, having become acquainted with Gauld’s humanized version of Goliath, readers see his death as a loss, David’s bravery a hollow triumph.

the Biblical phrases with which David approaches, proclaiming his intent to slay the giant, before we see him. And then—horrifyingly—we see centered on one full-page panel a rock . . . just a rock. We know even before turning the page that this is the ordinary stone that will doom Goliath. The “Thunk” that accompanies the stone’s hitting Goliath’s forehead is a stark contrast to the rolling, majestic Biblical phrases that accompany the following panels, where “victorious” David cuts off the giant’s head and takes it off in a sack to secure his destined future as a hero and, eventually, a worthy king. Rather than satisfaction at the end of this Biblical incident, we feel dismay. At this point, having become acquainted with Gauld’s humanized version of Goliath, readers see his death as a loss, David’s bravery a hollow triumph.

What truths lie behind the stories and reputations of heroes or leaders, real or legendary? How else may their stories be interpreted or fleshed out? Readers young and old who are challenged rather than dismayed (or possibly even offended) by such questions, particularly when they touch upon established religions, will appreciate the  midrashim I have discussed today. Those intrigued by the skeptical Miriam in The Lone and Level Sands might enjoy her heroism in the picture book Miriam’s Cup: A Passover Story (2006), written by Fran Manushkin and illustrated by Bob Dacey. Older readers might enjoy author/illustrator J.T. Waldman’s graphic novel about Queen Esther, Megillat Esther (2005). Its sumptuous black and white images and story may be previewed online here .

midrashim I have discussed today. Those intrigued by the skeptical Miriam in The Lone and Level Sands might enjoy her heroism in the picture book Miriam’s Cup: A Passover Story (2006), written by Fran Manushkin and illustrated by Bob Dacey. Older readers might enjoy author/illustrator J.T. Waldman’s graphic novel about Queen Esther, Megillat Esther (2005). Its sumptuous black and white images and story may be previewed online here .

As for me, I am awaiting my library copy of Punk Rock Jesus (2013), a compilation of the limited comic book series by author/illustrator Sean Murphy. Its controversial story of a cloned Jesus Christ received as much critical acclaim as it raised sometimes indignant feedback! And, even though it received mixed reviews, I think I shall try to download director Ridley Scott’s 2014 big-budget film Exodus: Gods and Kings. I want to see how well actor Christian Bale managed to fill Charlton Heston’s shoes! We all will have to wait until August, 2016 to see the latest remake of Ben-Hur, starring Jack Huston. Until then, the exceptionally popular 19th century novel upon which it is based—Lew Wallace’s Ben Hur; a Tale of the Christ—is available free online at Project Gutenberg.

As for me, I am awaiting my library copy of Punk Rock Jesus (2013), a compilation of the limited comic book series by author/illustrator Sean Murphy. Its controversial story of a cloned Jesus Christ received as much critical acclaim as it raised sometimes indignant feedback! And, even though it received mixed reviews, I think I shall try to download director Ridley Scott’s 2014 big-budget film Exodus: Gods and Kings. I want to see how well actor Christian Bale managed to fill Charlton Heston’s shoes! We all will have to wait until August, 2016 to see the latest remake of Ben-Hur, starring Jack Huston. Until then, the exceptionally popular 19th century novel upon which it is based—Lew Wallace’s Ben Hur; a Tale of the Christ—is available free online at Project Gutenberg.

These all sound excellent. I want to get my hands on The Lone and Level Sands, especially.

LikeLike