Springing into summer, we Minnesotans see bugs everywhere. Mosquitoes, those tiny terrors, have yet to be out in full force, but ants trail along sidewalks and beetles bustle in gardens. Out past my suburban home, farmers are readying their crops against infestation, while beekeepers statewide are trying to save diminished hives. It’s an apt time of year for a brand-new graphic novel by biology professor Jay Hosler, whose highly-praised Clan Apis (2000; 2013) packed so much emotion and humor, along with information, into its life cycle story of Nyuki, a honey bee. This time, in Last of the Sandwalkers (2015), gifted author/illustrator Hosler introduces us to the exciting world of beetles. Their abilities and sheer diversity may surprise readers of all ages, not just the middle school crowd Hosler originally targeted, even as the “human” traits of his characters capture our hearts and minds. There is nothing small at all in what beetles can do—or in Hosler’s accomplishments here! Last of the Sandwalkers is richly satisfying, a high point in popular culture’s longstanding interest in insect and arachnid life. I will touch on that tradition, still strong in comics and movie superheroes and villains, at the end of this post.

Springing into summer, we Minnesotans see bugs everywhere. Mosquitoes, those tiny terrors, have yet to be out in full force, but ants trail along sidewalks and beetles bustle in gardens. Out past my suburban home, farmers are readying their crops against infestation, while beekeepers statewide are trying to save diminished hives. It’s an apt time of year for a brand-new graphic novel by biology professor Jay Hosler, whose highly-praised Clan Apis (2000; 2013) packed so much emotion and humor, along with information, into its life cycle story of Nyuki, a honey bee. This time, in Last of the Sandwalkers (2015), gifted author/illustrator Hosler introduces us to the exciting world of beetles. Their abilities and sheer diversity may surprise readers of all ages, not just the middle school crowd Hosler originally targeted, even as the “human” traits of his characters capture our hearts and minds. There is nothing small at all in what beetles can do—or in Hosler’s accomplishments here! Last of the Sandwalkers is richly satisfying, a high point in popular culture’s longstanding interest in insect and arachnid life. I will touch on that tradition, still strong in comics and movie superheroes and villains, at the end of this post.

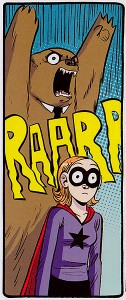

Last of the Sandwalkers is a fun and thrill-filled blend of genres—adventure, epic quest, family drama, and science fiction—which also lets Hosler fulfill his goal of “helping readers understand science better.” In fact, his beetle characters are themselves scientists, setting out to discover whether there is life outside their desert oasis home, a palm tree their civilization calls Coleopolis. Central character Lucy, a sandwalker beetle, excitedly believes there may be other living creatures, while senior Professor Owen scoffs at this possibility. Only when their expedition is well underway does Owen reveal his treacherous reasons for joining this quest—personal vanity and rigid religious beliefs. The existence of other creatures would threaten Coleopolis’s state religion, which worships a god called Scarabus. Owen’s sabotage does not diminish the joy the others take in their discoveries (a mouse skeleton and other insect species) or discourage them on their perilous trek homeward. (Those hungry bats and birds! That rushing stream and deep pond!) These determined scientists include Lucy’s adoptive parents and foster brother, who are two other kinds of beetle, with their own distinctive physical traits. Hosler helpfully introduces these characters in the opening “Graphic Guide to Identifying Beetles” and also provides chapter-by-chapter “Annotations” plus a bibliography at his book’s end. But it is the way he incorporates these traits into his characters’ personalities and their adventures that is most memorable.

Last of the Sandwalkers is a fun and thrill-filled blend of genres—adventure, epic quest, family drama, and science fiction—which also lets Hosler fulfill his goal of “helping readers understand science better.” In fact, his beetle characters are themselves scientists, setting out to discover whether there is life outside their desert oasis home, a palm tree their civilization calls Coleopolis. Central character Lucy, a sandwalker beetle, excitedly believes there may be other living creatures, while senior Professor Owen scoffs at this possibility. Only when their expedition is well underway does Owen reveal his treacherous reasons for joining this quest—personal vanity and rigid religious beliefs. The existence of other creatures would threaten Coleopolis’s state religion, which worships a god called Scarabus. Owen’s sabotage does not diminish the joy the others take in their discoveries (a mouse skeleton and other insect species) or discourage them on their perilous trek homeward. (Those hungry bats and birds! That rushing stream and deep pond!) These determined scientists include Lucy’s adoptive parents and foster brother, who are two other kinds of beetle, with their own distinctive physical traits. Hosler helpfully introduces these characters in the opening “Graphic Guide to Identifying Beetles” and also provides chapter-by-chapter “Annotations” plus a bibliography at his book’s end. But it is the way he incorporates these traits into his characters’ personalities and their adventures that is most memorable.

For instance, large Mossy with his huge mandibles and horn is protective of his foster parents and sister, even as they all good-naturedly bicker and tease each other. Upbeat Lucy may be frustrated at times by her family, but she never denies them the water that condenses on her bumpy, desert-adapted “shell.” Similarly, acerbic Professor Bombardier, who can literally spray her enemies with acid, has demandingly high professional standards for her family, but these mask genuine warmth and concern. These feelings extend to husband Raef, with his infuriating tendency to lose his head—literally, as well as figuratively, as Hosler reveals mid-book that Raef is a cyborg, with his beetle consciousness uploaded into a robot body! This science fiction element becomes important in the plot, but it is not the only science fiction aspect of this fantastic adventure. As Hosler has remarked in an interview, the variety of “adaptions [insects] have for survival” makes them seem like “super-powered aliens.” Hosler also recognizes how comics have developed such extraordinary characters, saying that this book is in some ways his tribute “to the Fantastic Four: a family with unique abilities, exploring the unknown and overcoming massive obstacles through teamwork.”

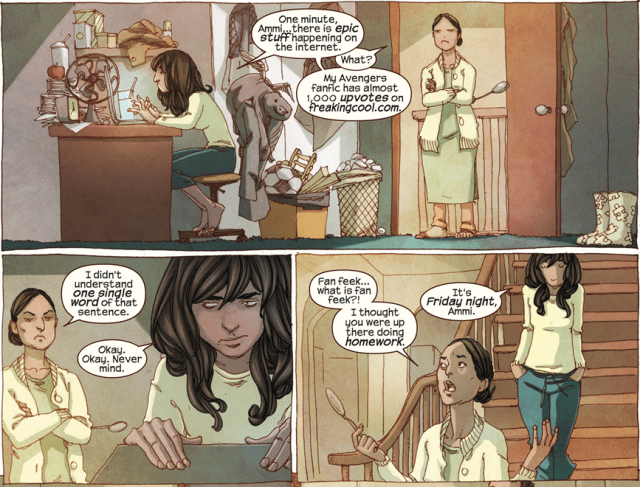

This author/illustrator acknowledges comics history in other ways. His expressively drawn, black-and-white characters include Ma’ Dog, the last of an imaginary beetle species Hosler terms the “Kama-Sheebay.” With their story-sticks displaying picture placards that illustrate spoken tales, these storytellers are a clear reference to Japan’s traditional kamishibai. Those wandering storytellers led up to Japan’s influential comics industry of written manga and filmed anime. Since the truth-telling “Kama-Sheebay” were outlawed generations ago from Coleopolis, Ma’Dog can knowledgeably help its scientists navigate the strange perils they face outside that oasis. Throughout these adventures, Hosler makes effective use of black backgrounds, varied panel size, and overlapping word balloons and figures to highlight and unite images. His artful shifts in perspective and distance also rivet our attention as we follow the story, its dramatic and humorous peaks often announced loudly by typographical changes. At other times, Hosler conveys more nuanced interactions through casual conversations, where the rhythms of informal, everyday speech ring true.

This author/illustrator acknowledges comics history in other ways. His expressively drawn, black-and-white characters include Ma’ Dog, the last of an imaginary beetle species Hosler terms the “Kama-Sheebay.” With their story-sticks displaying picture placards that illustrate spoken tales, these storytellers are a clear reference to Japan’s traditional kamishibai. Those wandering storytellers led up to Japan’s influential comics industry of written manga and filmed anime. Since the truth-telling “Kama-Sheebay” were outlawed generations ago from Coleopolis, Ma’Dog can knowledgeably help its scientists navigate the strange perils they face outside that oasis. Throughout these adventures, Hosler makes effective use of black backgrounds, varied panel size, and overlapping word balloons and figures to highlight and unite images. His artful shifts in perspective and distance also rivet our attention as we follow the story, its dramatic and humorous peaks often announced loudly by typographical changes. At other times, Hosler conveys more nuanced interactions through casual conversations, where the rhythms of informal, everyday speech ring true.

In interviews, this accomplished author/illustrator has been asked whether he plans a sequel to Last of the Sandwalkers, since we are never told how Raef comes to be a cyborg. I am encouraged by Hosler’s willingness to consider a sequel, as I am also curious about the gigantic skull of a “Hu-mon”—huge monkey, the beetles’ label for humans—the tiny scientists discover. How will their world-view (or ours) change if they encounter and can communicate with human beings? Like adventurous Lucy, skyrocketing off at the end of the book, we know that in this world of possibilities, “The real fun is just beginning!” That high note is a great way to round off both the physical adventures and the scientific inquiries of this energetic, hugely entertaining book.

In interviews, this accomplished author/illustrator has been asked whether he plans a sequel to Last of the Sandwalkers, since we are never told how Raef comes to be a cyborg. I am encouraged by Hosler’s willingness to consider a sequel, as I am also curious about the gigantic skull of a “Hu-mon”—huge monkey, the beetles’ label for humans—the tiny scientists discover. How will their world-view (or ours) change if they encounter and can communicate with human beings? Like adventurous Lucy, skyrocketing off at the end of the book, we know that in this world of possibilities, “The real fun is just beginning!” That high note is a great way to round off both the physical adventures and the scientific inquiries of this energetic, hugely entertaining book.

Eager readers, though, do not have to wait for that sequel to enjoy more of Professor Hosler’s graphic works. Besides Clan Apis, he has also authored The Sandwalk Adventures (2003), which humorously explains evolution through conversations between its exponent Sir Charles Darwin and a hair mite living in Darwin’s left eyebrow! (The possible “squick” factor here may be a plus for upper elementary and tween readers.)

Eager readers, though, do not have to wait for that sequel to enjoy more of Professor Hosler’s graphic works. Besides Clan Apis, he has also authored The Sandwalk Adventures (2003), which humorously explains evolution through conversations between its exponent Sir Charles Darwin and a hair mite living in Darwin’s left eyebrow! (The possible “squick” factor here may be a plus for upper elementary and tween readers.)  Some graphic pieces also appear in installments at Hosler’s science comics blog, “Drawing Flies.” The science there is sometimes high school level or above, but readers of all ages will take pleasure and learn from the blog’s multipart “Field Guide to Superpowers.” It compares comic book superheroes old and new with natural creatures—including beetles, spiders, and ants—which actually have each hero’s “superpowers,” scaled down to the creatures’ sizes and environment.

Some graphic pieces also appear in installments at Hosler’s science comics blog, “Drawing Flies.” The science there is sometimes high school level or above, but readers of all ages will take pleasure and learn from the blog’s multipart “Field Guide to Superpowers.” It compares comic book superheroes old and new with natural creatures—including beetles, spiders, and ants—which actually have each hero’s “superpowers,” scaled down to the creatures’ sizes and environment.

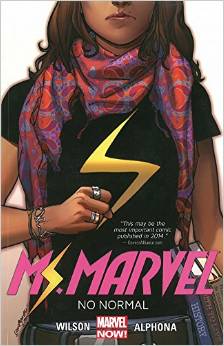

Similar scientific accuracy is not always evident in the comics themselves! But scientific curiosity is not the main reason that readers enjoy these works and their movie spin-offs. Spiderman may be the best known “bug” superhero, but it is Peter Parker’s teenage problems as much as his adventures that hold our interest. The same may be said about the most recent incarnation of the “Blue Beetle,” a crime-fighting superhero who first appeared in the 1930s. During the 1960s Cold War, he reappeared to battle the USA’s Communist enemies. In the 1990s, the “Blue Beetle” was more of a humorous character. Between 2011 and 2013, though, a Texas teenager named Jaime Reyes was featured as the “new” Blue Beetle in a series of seventeen comic books.  These have been collected in several paperback compilations, beginning with Blue Beetle, Volume 1 Metamorphosis (Comics issues 1-6, 2011; 2012). Young readers may appreciate how Jaime copes there with problems ranging from everyday life to alien invasions. They may already know this character from his guest appearances on superhero animated and live action TV shows such Smallville.

These have been collected in several paperback compilations, beginning with Blue Beetle, Volume 1 Metamorphosis (Comics issues 1-6, 2011; 2012). Young readers may appreciate how Jaime copes there with problems ranging from everyday life to alien invasions. They may already know this character from his guest appearances on superhero animated and live action TV shows such Smallville.

“Ant-Man” is another “bug” superhero who first appeared in the 1960s, with different human characters assuming his costume and powers. Some were even criminals who took this opportunity to reform their ways. At times, Ant Man was joined by superhero “Wasp Woman” – a very different character than the villainous Wasp Woman (or other mutated “bug” monsters) of 1940s and 50s movie thrillers.  A new feature film about “Ant Man” debuts in movie theaters next month. Will it make our eyes and minds “bug out” with excitement? Will a Wasp Woman make an appearance in this film? Summer is certainly the right season for ants and such critters to flourish. . . .

A new feature film about “Ant Man” debuts in movie theaters next month. Will it make our eyes and minds “bug out” with excitement? Will a Wasp Woman make an appearance in this film? Summer is certainly the right season for ants and such critters to flourish. . . .

![Shaun Tan - The Arrival 112-113[1]](https://natalierosinsky.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/shaun-tan-the-arrival-112-1131.jpg?w=640&h=430)