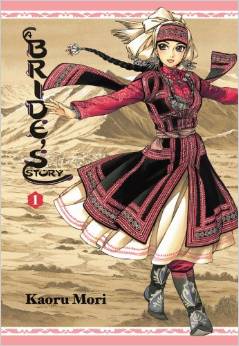

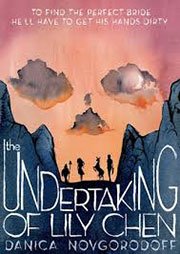

Spurred by invitations to weddings this June, the traditional month for them in Western society, I took pleasure this past week in reading vivid, skillful graphic novels about non-Western weddings and ways. Just published, Danica Novgorodoff’s The Undertaking of Lily Chen (2014) centers upon a dramatic marriage custom that is atypical in far away (from us) modern China. Kaoru Mori’s manga series A Bride’s Story (2009 – 2013), on the other hand, recreates what typical life and marriage customs were like during the late 19th century, in what is now Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan. These countries were once part of the famed Silk Road trade routes, stretching from western China to Baghdad and Antioch.

Japanese author/illustrator Mori explains in the lively “AFTERWORD TAN-TA-DAAH MANGA” to Volume 1 of A Bride’s Story how her fascination with Silk Road life began in middle and high school. Books, museum exhibits, and carpet displays fed the now-36 year old’s enthusiasm, as she began to think “about what kind of woman I’d like to see in a central Asian setting.” That is how she came up with the character of Amir, the 20 year old bride central to the first two volumes of this five volume series. (Volume six will be published in English in October, 2014.) Amir, from a highly nomadic tribe, is more daring and athletic than the women of the primarily village-dwelling family into which she marries. Yet she is also eager to please her new husband and relatives, not always understanding how their customs differ as well as overlap with hers.

Early in the first volume, this difference is captured wonderfully in a series of wordless pages depicting Amir’s impetuous horse ride to hunt down rabbits for dinner. Long and mid-distance panels of Amir galloping after a rabbit alternate with close-ups of the fleeing animal and of Amir drawing an arrow through her bow, aiming, and letting it fly.

A ground-view panel then breathtakingly unites both figures, depicting the rabbit pierced mid-leap and horse hooves mid-gallop. Her worried husband Karluk, who with friends has raced after Amir, sees her swoop up her first kill while she is still on horseback! Later, Amir proudly displays and prepares rabbits for the family’s meal. Reading about this arranged marriage, I was relieved that author Mori showed Amir’s new family adapting to Amir, accepting many of her differences even as she learns their customs, too. Another point of relief was Mori’s treatment of the young couple’s age difference: groom Karluk is (not unusual for his time and place) twelve years old, but the pair is depicted in a ‘big sister and little brother’ relationship. Karluk sleepily thinks at the end of the day that a “lamb sleeping with its mother . . . must feel just like this.” The series contains brief scenes of nudity during baths and at night, but this nudity is not sexual for the characters.

Despite its title, the first two volumes of A Bride’s Story are more about family life and children acquiring adult skills and responsibilities than they are about romance. In volume one, Karluk’s younger brother Rostem wanders off to observe a carpenter, whose woodworking talents include elaborate, detailed carving. Through wordless close-ups swirling with energy and others begging to be touched, Mori makes us feel Rostem’s fascination—an interest that may direct his childish energies towards adulthood. Similarly, in volume two, Karluk’s niece Tileke—whose idiosyncratic, ‘tomboyish’ love of hawks is tolerated by her family—learns how the intricate, embroidered patterns of clothing and bedding contain the history (and personalities) of her female relatives. Tileke comes to value this heritage. In wordless close-ups and then in a narrated double-page spread, Mori’s detailed drawings communicate the richness of central Asian culture. We understand why she enthuses, in that second volume’s “AFTERWORD,” that when she sits and draws “horses’ legs, or embroidery . . . details, details . . . . YES, I FEEL SO ALIVE!”

Volumes three through five follow a British guest in Karluk and Amir’s household as he journeys onward, meeting other would-be and actual brides. Tradition thwarts the hopes of one young widow for remarriage, while fifteen year old twins Laila and Leily humorously scheme to matchmake for themselves. These clever, bold, sometimes annoying teens are determined to marry wealthy brothers—so as married women they can continue to live near one another in comfort. Most of their schemes fail, but the pair end up pleased with their grooms—neighboring young men, brothers with limited income, whom they have known lifelong. Mori’s words and images also show this courtship and marriage from the brothers’ viewpoint, enriching our understanding of how familiarity ultimately leads to friendship, and then affection and devotion. Enduring the formal festivities of a typical, weeklong wedding celebration is one stress that draws the couples closer. While these central events take place, Mori reintroduces Amir and Karluk, as they travel with other relatives on tribal business. We see that couple’s increasing closeness, which by the end of volume five has Karluk chastely kissing his bride and jealous of her time spent away from him. Their ‘big sister and little brother’ relationship is slowly changing, even as Karluk himself seems unaware of this change and Amir does nothing to hasten it.

Mori’s series is enriched by “Bonus Chapters” and “Side Stories” which detail more about background characters. In volume three’s “Pariya Is At That Age,” we discover how this feisty teenager from Karluk’s tribe is happy that her temper and strong opinions are scaring away potential grooms! Her story becomes a subplot in later volumes. In volume five’s “Queen of the Mountain,” Karluk’s wise grandmother, herself from a nomadic tribe, surprises village youngsters by riding a mountain goat to rescue a stranded child. The complete A Bride’s Story series recently won Japan’s 2014 Manga Taisho (Cartoon Grand Prize), an honor bestowed by booksellers. In 2012, the first volume of this engaging series was named one of YALSA’s Top Ten Graphic Novels for Teens.

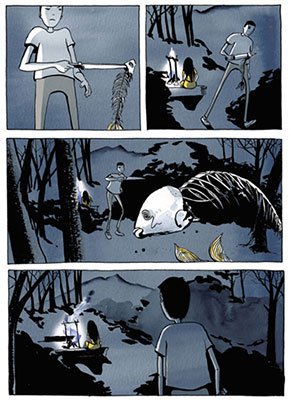

Like Mori, author/illustrator Danica Novgorodoff in The Undertaking of Lily Chen makes extensive, effective use of wordless panels. This is evident right from the Prologue, where readers may deduce the fatal consequence of two brothers’ fist fight from its climactic panel, an image of one young man’s broken eyeglasses next to a puddle of blood. Unlike the black-and-white Bride’s Story, though, Lily Chen uses a full color palette. In an online interview, Novgorodoff explains that she used “watercolor paper with a combination of watercolor paint and ink, using . . . long flexible animal hair brushes . . . as well as tiny brushes for detail” to reproduce landscapes she had seen on two trips to China. The ‘painterly’ look of many pages in this novel—as well as its tone—is often very different than the detailed drawing and general high spirits of Mori’s manga series.

Novogorodoff explains that she was inspired by a magazine article in 2007 describing the reoccurrence today in northern China of an ancient tradition: providing a man who has died unmarried with a ‘ghost bride’ to keep him company in the afterlife. This is accomplished by holding a wedding ceremony before the man’s funeral, marrying him to a woman who has died earlier, and then reburying this ‘bride’ alongside her new ‘husband.’ Novogorodoff poetically notes how this tradition is said to have begun with an ancient emperor grieving the death of his 13 year old heir: “Dear Son . . . who will hold your hand as your approach the gates of heaven? Who will lie with you in the dark eternal bedroom?” In the novel, after their favorite son, college-aged Wei, is accidentally killed in that fight by his slightly younger brother, Deshi, their parents order Deshi to find such a ‘ghost bride’ for Wei. He will need to purchase or otherwise obtain a corpse for this purpose.

Deshi has a little more than a week to accomplish this task—an enormous “undertaking” in emotional as well physical terms. Illustrations accompanying each new chapter—the stylized faces of traditional Chinese gods and demons, an abacus with shifted beads that mark each passing day, and the ‘wedding gown’ that Wei’s mother painstakingly makes for the corpse bride—highlight the mounting pressure on guilt-ridden Deshi. This young man must deal with criminals as well as sharp-tongued Lily Chen, a runaway young woman who wants a new, exciting life for herself in ‘the big city,’ as he desperately tries to satisfy his parents’ strident demands. (They brutally tell Deshi that they wish he, not Wei, had died.) Along the way, Deshi even has to come to terms with what appears to be Wei’s ghost, called upon at night by monks in a Buddhist temple. Parts of his blue-tinged, ghastly face are the sole, central images on several otherwise white, wordless pages in this chapter titled “Temple.”

The Undertaking of Lily Chen balances many elements: its plot contains romance as well as violence, humor as well as grief, a villain’s casual purchase of sex as well as Deshi and Lily’s spontaneous, heartfelt coupling, silhouetted against the glowing embers of a riverside campfire. Novogorodoff herself even humorously describes this episodic graphic novel as “a sort of western, complete with a journey on horseback, a bad guy with a pencil mustache, a knife fight, and a fistful of dollars (well, yuan).” (That sort of wry humor also shows up in the novel when its pictures conflict with what is said. For instance, the cartoonlike misfits Lily’s father calls upon to help him track her—lame, old, or doltishly nose picking—are not, one assumes, really his “town’s bravest, strongest, and most trustworthy men.”)

While this mixture of genres and visual styles might sound too strange to work, I think the novel’s consistent color palette, along with the water color, ‘painted’ images conveying the feelings and dreams of both Deshi and Lily, unite all these elements into a successful whole. Deshi’s early fearfulness and self-doubt are offset and finally overcome by Lily’s bold confidence. Together, the pair face down dangers, including some self-imposed ones. Novgorodoff shows Deshi and Lily breaking away from tradition and their past roles as dutiful children without destroying those traditions or relationships—just she depicts the steel cranes and modern highways which exist in China today alongside misty mountain scenes first captured in thousand year old, hand painted scrolls.

(These scenes echo the photography of 21st century Shanghai artist Yang Yongliang , who manipulates images to spotlight such connections.) But I do not want to spoil the ending of this memorable, entertaining book for you. To see how Deshi and Lily end up showing respect and regard for both his cruel if grief stricken parents and her angry but concerned father, you will need to read The Undertaking of Lily Chen yourself! If, having read the novel, you think as I do that Deshi has been too respectful to his narrow-minded, verbally abusive parents, please let me know.

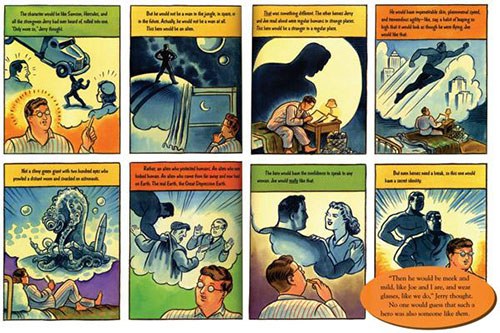

Picture book biography Boys of Steel: The Creators of Superman (2008), written by Marc Tyler Nobleman and illustrated by Ross MacDonald, does a fine job of explaining what led teenagers Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster to ‘invent’ this superhero. His powers could combat Depression-era problems and World War II dangers in ways author Siegel and illustrator Shuster could not. Superman’s popularity was also a satisfying, wish-fulfilling contrast to their own daily lives, which were much more like their hero’s socially-awkward ‘secret identity,’ Clark Kent. MacDonald’s vivid, boldly-outlined illustrations are an affectionate tribute to the drawing and inking styles of the original books. His composition of images—such as the double-spread framing of Siegel and Schuster’s work sessions as a typical comic book, with four panels to a page—is smart and snappy. Nobleman’s apt, upbeat wording ends this saga on a high note, with the teens watching the creation they “brought … to Earth … become a superstar” as MacDonald’s ‘Man of Steel’ soars up and away from them.

Picture book biography Boys of Steel: The Creators of Superman (2008), written by Marc Tyler Nobleman and illustrated by Ross MacDonald, does a fine job of explaining what led teenagers Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster to ‘invent’ this superhero. His powers could combat Depression-era problems and World War II dangers in ways author Siegel and illustrator Shuster could not. Superman’s popularity was also a satisfying, wish-fulfilling contrast to their own daily lives, which were much more like their hero’s socially-awkward ‘secret identity,’ Clark Kent. MacDonald’s vivid, boldly-outlined illustrations are an affectionate tribute to the drawing and inking styles of the original books. His composition of images—such as the double-spread framing of Siegel and Schuster’s work sessions as a typical comic book, with four panels to a page—is smart and snappy. Nobleman’s apt, upbeat wording ends this saga on a high note, with the teens watching the creation they “brought … to Earth … become a superstar” as MacDonald’s ‘Man of Steel’ soars up and away from them.

Readers learn that “today, on every story where [Superman’] name appears, [Jerry and Joe’s] do, too.” Only in Nobleman’s detailed, picture-less three page afterword will curious, able readers learn how corporate business practices for many intervening years deprived Superman’s creators of their due. Nobleman’s decision to divide the biography in this way is a wise one, emotionally satisfying and historically accurate for a range of young readers who might be ready for differing amounts of detail. Older readers may also be interested in a new biography by Case Western Reserve University scholar Brad Ricca, Super Boys: The Amazing Adventures of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster—The Creators of Superman (2013). This entertaining, often movingly written book begins with the robbery-murder of 17 year old Jerry Siegel’s father and is illustrated with photographs along with panels from Golden Age comics.

Readers learn that “today, on every story where [Superman’] name appears, [Jerry and Joe’s] do, too.” Only in Nobleman’s detailed, picture-less three page afterword will curious, able readers learn how corporate business practices for many intervening years deprived Superman’s creators of their due. Nobleman’s decision to divide the biography in this way is a wise one, emotionally satisfying and historically accurate for a range of young readers who might be ready for differing amounts of detail. Older readers may also be interested in a new biography by Case Western Reserve University scholar Brad Ricca, Super Boys: The Amazing Adventures of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster—The Creators of Superman (2013). This entertaining, often movingly written book begins with the robbery-murder of 17 year old Jerry Siegel’s father and is illustrated with photographs along with panels from Golden Age comics. Another picture book by Nobleman, Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman (2012), illustrated by Ty Templeton, unveils the ‘secret identity’ of modest Bill Finger. This comic book writer came up with many of the ideas for Batman, although for years illustrator Bob Kane received sole credit for the brooding superhero’s appearance, back story, and adventures. Templeton effectively advances Finger’s biography by drawing panels of different sizes and shapes, alternating close-ups with mid-distance views, and uniting frames with twisted logic as running figures or flying darts move from one panel into another. Nobleman has fun playing with words as Bill Finger himself liked to do. Nobleman writes that “[Comics readers] loved when Bill was at Bat” and that, even while Bill’s contributions were secret, “Bat-Man had Bill’s Fingerprints all over him . . . .” Humility plus the sheer pleasure of a job well done seem to have motivated Bill Finger’s decades-long silence about his creative input. Before his death in 1974, though, he had begun to receive some recognition. In a detailed, six page Author’s Note, Nobleman again addresses a broader range of readers, explaining his research into Bill Finger’s life and providing further information about his family and his personal and professional legacies.

Another picture book by Nobleman, Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman (2012), illustrated by Ty Templeton, unveils the ‘secret identity’ of modest Bill Finger. This comic book writer came up with many of the ideas for Batman, although for years illustrator Bob Kane received sole credit for the brooding superhero’s appearance, back story, and adventures. Templeton effectively advances Finger’s biography by drawing panels of different sizes and shapes, alternating close-ups with mid-distance views, and uniting frames with twisted logic as running figures or flying darts move from one panel into another. Nobleman has fun playing with words as Bill Finger himself liked to do. Nobleman writes that “[Comics readers] loved when Bill was at Bat” and that, even while Bill’s contributions were secret, “Bat-Man had Bill’s Fingerprints all over him . . . .” Humility plus the sheer pleasure of a job well done seem to have motivated Bill Finger’s decades-long silence about his creative input. Before his death in 1974, though, he had begun to receive some recognition. In a detailed, six page Author’s Note, Nobleman again addresses a broader range of readers, explaining his research into Bill Finger’s life and providing further information about his family and his personal and professional legacies.

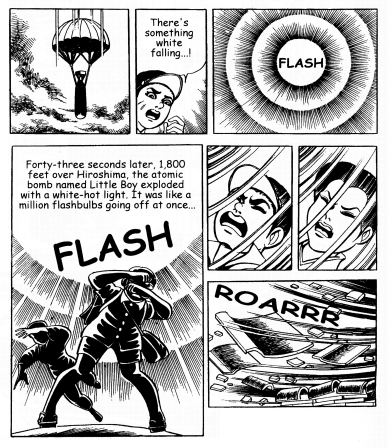

Experiencing World War II’s dangers and devastation at a young age motivated two other graphic book makers, Lily Renée Wilhelm and Keiji Nakazawa. Young readers and others can learn about Lily Renée’s life in the deft graphic biography, Lily Renée, Escape Artist: From Holocaust Survivor to Comic Book Pioneer (2011), written by Trina Robbins and illustrated by Anne Timmons and Mo Oh. Keiji Nakazawa, who as a six-year old survived Hiroshima’s atomic blast, went on to create a ten-volume manga about his childhood, titled in English Barefoot Gen (1973–1985; 2008–2010).

Experiencing World War II’s dangers and devastation at a young age motivated two other graphic book makers, Lily Renée Wilhelm and Keiji Nakazawa. Young readers and others can learn about Lily Renée’s life in the deft graphic biography, Lily Renée, Escape Artist: From Holocaust Survivor to Comic Book Pioneer (2011), written by Trina Robbins and illustrated by Anne Timmons and Mo Oh. Keiji Nakazawa, who as a six-year old survived Hiroshima’s atomic blast, went on to create a ten-volume manga about his childhood, titled in English Barefoot Gen (1973–1985; 2008–2010).

The back matter to this biography, titled “More about Lily’s Story,” contains detailed essays about Nazi Germany, Britain’s traditions and war time policies, and New York life, including the 1940s comic book industry. Fascinating illustrations here include not only photos in “Lily’s Family Album” but 1940s comic pages illustrated by women, some by Lily Renée herself. Older readers whose interest is piqued by these pages may enjoy Trina Robbins’ latest publication, Pretty in Ink: North American Women Cartoonists, 1896–2013 (2013). Four of its 180 colorful pages are devoted to Lily Renee and include larger reproductions of comic book pages and covers she illustrated.

The back matter to this biography, titled “More about Lily’s Story,” contains detailed essays about Nazi Germany, Britain’s traditions and war time policies, and New York life, including the 1940s comic book industry. Fascinating illustrations here include not only photos in “Lily’s Family Album” but 1940s comic pages illustrated by women, some by Lily Renée herself. Older readers whose interest is piqued by these pages may enjoy Trina Robbins’ latest publication, Pretty in Ink: North American Women Cartoonists, 1896–2013 (2013). Four of its 180 colorful pages are devoted to Lily Renee and include larger reproductions of comic book pages and covers she illustrated. Keiji Nakazawa’s powerful, ten-volume autobiography for reasons of length as much as subject matter is best suited for readers tween and older. Those who tackle Barefoot Gen may also be interested in viewing the documentary film,

Keiji Nakazawa’s powerful, ten-volume autobiography for reasons of length as much as subject matter is best suited for readers tween and older. Those who tackle Barefoot Gen may also be interested in viewing the documentary film,

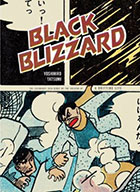

Another autobiographical manga, Yoshiro Tatsumi’s A Drifting Life (2009–2011), demonstrates that the ‘serious matters’ motivating graphic artists are not always devastating ones. In fact, they can be profoundly joyful. Besides providing a history of the manga industry after World War II through the 1960s, including debates about how to draw characters and tell stories, this Eisner Award-winning book captures how magical moments of creativity can be. Twenty-one year old Hiroshi (the author/illustrator’s renamed self) is so caught up in working on the thriller novel Black Blizzard (1956; 2010) that “while working on the scene of extreme cold . . . he actually shivered.” Tatsumi depicts this feeling as dark sheets of wind and snow implausibly lashing him during a work session at his indoor drawing board. This blizzard is also the panel background to a wide-eyed moment of realization, when he thinks, “So this is the thrill of creation! I had no idea.” He next compares it to the “runner’s high” experienced by athletes, “as their bodies start to feel light, and they feel free in both body and mind.” Four panels on this five-paneled page show runners pushing themselves in a race, but the fifth, final panel shows exultant Hiroshi, resting backwards away from his page-filled writing desk, holding onto a paper, as he experiences “his own version of a ‘runner’s high.’”

Another autobiographical manga, Yoshiro Tatsumi’s A Drifting Life (2009–2011), demonstrates that the ‘serious matters’ motivating graphic artists are not always devastating ones. In fact, they can be profoundly joyful. Besides providing a history of the manga industry after World War II through the 1960s, including debates about how to draw characters and tell stories, this Eisner Award-winning book captures how magical moments of creativity can be. Twenty-one year old Hiroshi (the author/illustrator’s renamed self) is so caught up in working on the thriller novel Black Blizzard (1956; 2010) that “while working on the scene of extreme cold . . . he actually shivered.” Tatsumi depicts this feeling as dark sheets of wind and snow implausibly lashing him during a work session at his indoor drawing board. This blizzard is also the panel background to a wide-eyed moment of realization, when he thinks, “So this is the thrill of creation! I had no idea.” He next compares it to the “runner’s high” experienced by athletes, “as their bodies start to feel light, and they feel free in both body and mind.” Four panels on this five-paneled page show runners pushing themselves in a race, but the fifth, final panel shows exultant Hiroshi, resting backwards away from his page-filled writing desk, holding onto a paper, as he experiences “his own version of a ‘runner’s high.’”

Making manga for teens and adults rather than children, Tatsumi coined the term “gekiga”—translated as “dramatic pictures”—for both the faster pace and darker content of this kind of manga. Tweens and teens will appreciate the melodrama of Black Blizzard’s convict escape and circus romance, but several of Tatsumi’s ground-breaking manga collections, such as Good-Bye (1971–72; 2008) and Abandon the Old in Tokyo (1970; 2006) with their bleak pictures of psychological and social outsiders in post-war Japan, may disturb or distress even some sophisticated readers. A few of their well-crafted stories seem designed to provoke uneasy laughter—and that’s no joke, even on April Fool’s Day. Adults should be prepared to talk about these stories if older teen readers need help in processing their content. Similarly, the animated film Tatsumi (2011) based on A Drifting Life and several of these complex short stories, should be considered “R-rated.”

Making manga for teens and adults rather than children, Tatsumi coined the term “gekiga”—translated as “dramatic pictures”—for both the faster pace and darker content of this kind of manga. Tweens and teens will appreciate the melodrama of Black Blizzard’s convict escape and circus romance, but several of Tatsumi’s ground-breaking manga collections, such as Good-Bye (1971–72; 2008) and Abandon the Old in Tokyo (1970; 2006) with their bleak pictures of psychological and social outsiders in post-war Japan, may disturb or distress even some sophisticated readers. A few of their well-crafted stories seem designed to provoke uneasy laughter—and that’s no joke, even on April Fool’s Day. Adults should be prepared to talk about these stories if older teen readers need help in processing their content. Similarly, the animated film Tatsumi (2011) based on A Drifting Life and several of these complex short stories, should be considered “R-rated.”  When my son (now 27) was a tot, library story time was an important part of our week. We both looked forward to that circle of eager kids, listening and watching as the librarian dramatically pointed out scenes in the picture books she read. Wisely, she encouraged youthful murmurs, gasps, and even shouted-out replies. I did not know then that our Mankato, Minnesota routine—a long-held custom in many places—echoed one of the forerunners of

When my son (now 27) was a tot, library story time was an important part of our week. We both looked forward to that circle of eager kids, listening and watching as the librarian dramatically pointed out scenes in the picture books she read. Wisely, she encouraged youthful murmurs, gasps, and even shouted-out replies. I did not know then that our Mankato, Minnesota routine—a long-held custom in many places—echoed one of the forerunners of  Perhaps you already know about “paper theater” through award-winning author/illustrator Allen Say’s picture book Kamishibai Man (2005). In his Foreword to that nostalgic, moving story, Say explains how, as a child in 1930s Japan, he eagerly awaited the appearance of his neighborhood’s bicycle-riding storyteller. Such kamishibai men sold sweets before shuffling sturdy paper pictures through the frame of a portable wooden ‘stage.’ In her Afterword to this book, folklore scholar Tara McGowan gives further information about the origins and enormous popularity of kamishibai from the 1920s through early 1950s, when television replaced this street-performance art. Say cleverly uses two different styles of drawing to show the impact of this change on his character old Jiichan, who used to be a kamishibai man.

Perhaps you already know about “paper theater” through award-winning author/illustrator Allen Say’s picture book Kamishibai Man (2005). In his Foreword to that nostalgic, moving story, Say explains how, as a child in 1930s Japan, he eagerly awaited the appearance of his neighborhood’s bicycle-riding storyteller. Such kamishibai men sold sweets before shuffling sturdy paper pictures through the frame of a portable wooden ‘stage.’ In her Afterword to this book, folklore scholar Tara McGowan gives further information about the origins and enormous popularity of kamishibai from the 1920s through early 1950s, when television replaced this street-performance art. Say cleverly uses two different styles of drawing to show the impact of this change on his character old Jiichan, who used to be a kamishibai man. While readers of all ages will enjoy Kamishibai Man, older readers already interested in manga or Japan will best appreciate Eric P. Nash’s gorgeously illustrated history book, Manga Kamishibai: The Art of Japanese Paper Theater (2009). Nash details how kamishibai performances typically would have three tales in different genres, including comedy, daily life, and action-adventure. Long before Batman appeared in the United States, the adventures of costumed superhero Golden Bat were thrilling kamishibai audiences! Yet U.S. tales, comics, and cartoons themselves influenced some “paper theater,” which featured characters modeled on Tarzan and wide-eyed Betty Boop and heroic sheriffs as well as samurai warriors. Nash also explains how the kamishibai industry worked, with writers and artists selling their stories to businessmen, who then rented the completed story boards to storytellers like Allen Say’s Jiichan. As TV replaced kamishibai as popular entertainment, its writers and artists worked more on manga printed in newspapers and magazines. Well-known manga creators who got their start this way include Kazuo Koike (writer of the epic Lone Wolf and Cub series) and Shigeru Mizuki (author/illustrator of Kitaro). They brought other visual narrative techniques from kamishibai, such as cinematic close-ups, to manga.

While readers of all ages will enjoy Kamishibai Man, older readers already interested in manga or Japan will best appreciate Eric P. Nash’s gorgeously illustrated history book, Manga Kamishibai: The Art of Japanese Paper Theater (2009). Nash details how kamishibai performances typically would have three tales in different genres, including comedy, daily life, and action-adventure. Long before Batman appeared in the United States, the adventures of costumed superhero Golden Bat were thrilling kamishibai audiences! Yet U.S. tales, comics, and cartoons themselves influenced some “paper theater,” which featured characters modeled on Tarzan and wide-eyed Betty Boop and heroic sheriffs as well as samurai warriors. Nash also explains how the kamishibai industry worked, with writers and artists selling their stories to businessmen, who then rented the completed story boards to storytellers like Allen Say’s Jiichan. As TV replaced kamishibai as popular entertainment, its writers and artists worked more on manga printed in newspapers and magazines. Well-known manga creators who got their start this way include Kazuo Koike (writer of the epic Lone Wolf and Cub series) and Shigeru Mizuki (author/illustrator of Kitaro). They brought other visual narrative techniques from kamishibai, such as cinematic close-ups, to manga. From the kamishibai Golden Bat to … the Green Turtle? That somewhat surprisingly-named superhero’s first comic book adventures, published in 1940s America, had him helping the Chinese in their real-life struggles against Japanese invaders, which began in the 1930s and continued throughout World War II.

From the kamishibai Golden Bat to … the Green Turtle? That somewhat surprisingly-named superhero’s first comic book adventures, published in 1940s America, had him helping the Chinese in their real-life struggles against Japanese invaders, which began in the 1930s and continued throughout World War II. Yang and Lieuw’s origin story for the Green Turtle, titled The Shadow Hero (2014), develops this idea. The Shadow Hero begins in China and follows immigrants to the U.S. as they meet, marry, and settle into a California Chinatown. It is their grown son, in that 1930s and ’40s Chinatown, who will—with conflicted emotions, including rueful humor at his strong-minded mother’s ambitions for him—become the Shadow Hero. I cannot tell you how this story reaches that conclusion, though, because I have only read the first chapter! Publisher First Second is debuting The Shadow Hero online in serial form, a chapter a month, before finally making the whole, six-chapter book available in July, 2014. First Second is, they say, “paying homage” to the suspenseful anticipation 1930s and ’40s readers experienced as they waited for new issues of that era’s serialized comics. Chapter One of The Shadow Hero debuted on February 18, 2014, available for downloadable purchase on Amazon Kindle, Apple ibooks, and Barnes & Noble Nook. If you wish, you can catch up and join in the suspenseful anticipation as Chapter Two becomes available this month on March 18 ….

Yang and Lieuw’s origin story for the Green Turtle, titled The Shadow Hero (2014), develops this idea. The Shadow Hero begins in China and follows immigrants to the U.S. as they meet, marry, and settle into a California Chinatown. It is their grown son, in that 1930s and ’40s Chinatown, who will—with conflicted emotions, including rueful humor at his strong-minded mother’s ambitions for him—become the Shadow Hero. I cannot tell you how this story reaches that conclusion, though, because I have only read the first chapter! Publisher First Second is debuting The Shadow Hero online in serial form, a chapter a month, before finally making the whole, six-chapter book available in July, 2014. First Second is, they say, “paying homage” to the suspenseful anticipation 1930s and ’40s readers experienced as they waited for new issues of that era’s serialized comics. Chapter One of The Shadow Hero debuted on February 18, 2014, available for downloadable purchase on Amazon Kindle, Apple ibooks, and Barnes & Noble Nook. If you wish, you can catch up and join in the suspenseful anticipation as Chapter Two becomes available this month on March 18 …. Part graphic novel, part prose: this mixed-genre form of writing has gained popularity since the debut of Brian Selznick’s delightful The Invention of Hugo Cabret (2007). That Caldecott award-winner and Selznick’s acclaimed Wonderstruck (2011), with their twelve-year-old protagonists, are both subtitled “A Novel in Words and Pictures,” each consisting of more than one-third pictures. As Selznick himself points out, though, those books’ eloquent pictures are completely wordless—their many double-page spreads are like motion picture images, zooming in and out of close-ups, or like the wordless panels inside some comics. A gifted author/illustrator, Selznick has yet to tackle the multi-paneled pages, with dialogue balloons or prose boxes, typical of graphic novels. That more typical format has appeared with growing frequency in books for kids and young adult readers.

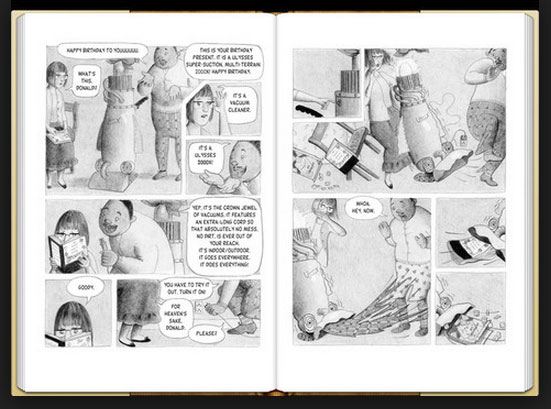

Part graphic novel, part prose: this mixed-genre form of writing has gained popularity since the debut of Brian Selznick’s delightful The Invention of Hugo Cabret (2007). That Caldecott award-winner and Selznick’s acclaimed Wonderstruck (2011), with their twelve-year-old protagonists, are both subtitled “A Novel in Words and Pictures,” each consisting of more than one-third pictures. As Selznick himself points out, though, those books’ eloquent pictures are completely wordless—their many double-page spreads are like motion picture images, zooming in and out of close-ups, or like the wordless panels inside some comics. A gifted author/illustrator, Selznick has yet to tackle the multi-paneled pages, with dialogue balloons or prose boxes, typical of graphic novels. That more typical format has appeared with growing frequency in books for kids and young adult readers. So different in tone, these books are alike in the seamless, effective ways in which their graphic portions advance plot, deepen character, and explore themes. I was surprised to learn that Kate DiCamillo, an award-winning author, had originally written Flora & Ulysses entirely in prose. In an interview, DiCamillo admiringly says that Candlewick Press’s editorial and design departments had the “brilliant” idea to incorporate graphic elements into this novel. Knowing this adds luster to K.G. Campbell’s achievements in so smoothly “illuminating” this work, using one of his preferred media, pencil, with ongoing direction from his editor and input from DiCamillo.

So different in tone, these books are alike in the seamless, effective ways in which their graphic portions advance plot, deepen character, and explore themes. I was surprised to learn that Kate DiCamillo, an award-winning author, had originally written Flora & Ulysses entirely in prose. In an interview, DiCamillo admiringly says that Candlewick Press’s editorial and design departments had the “brilliant” idea to incorporate graphic elements into this novel. Knowing this adds luster to K.G. Campbell’s achievements in so smoothly “illuminating” this work, using one of his preferred media, pencil, with ongoing direction from his editor and input from DiCamillo. Ulysses’ new world is shaped by the experience and interests of ten year old Flora, for whom comic book super heroes such as the “Great Incandestro” are as real—and more understandable—than her divorced parents. Her romance-writing mother and always-introducing-himself father are larger than life in their foibles, as are the other characters and events in this fantastic novel. Yet the emotions depicted in these Illuminated Adventures are real: children’s need for the supportive love of parents, young people’s need to name themselves as they grow as individuals, the pain and problems that come with divorce, the healing and strengthening power of friendship. Is the “Squirrel Poetry” in the Epilogue, purportedly written by Ulysses, too pat or just right … ? It may depend on the reader. Or, as eleven year-old William Spiver, another wonderfully over-the-top character in the book remarks, “The truth … is a slippery thing. I doubt that you will ever get to The Truth.” It is that kind of observation that for me makes fanciful Flora & Ulysses a nourishing read as well as a delightful confection.

Ulysses’ new world is shaped by the experience and interests of ten year old Flora, for whom comic book super heroes such as the “Great Incandestro” are as real—and more understandable—than her divorced parents. Her romance-writing mother and always-introducing-himself father are larger than life in their foibles, as are the other characters and events in this fantastic novel. Yet the emotions depicted in these Illuminated Adventures are real: children’s need for the supportive love of parents, young people’s need to name themselves as they grow as individuals, the pain and problems that come with divorce, the healing and strengthening power of friendship. Is the “Squirrel Poetry” in the Epilogue, purportedly written by Ulysses, too pat or just right … ? It may depend on the reader. Or, as eleven year-old William Spiver, another wonderfully over-the-top character in the book remarks, “The truth … is a slippery thing. I doubt that you will ever get to The Truth.” It is that kind of observation that for me makes fanciful Flora & Ulysses a nourishing read as well as a delightful confection. Best friends, Chicago high school seniors Holly Trask and Savitri Mathur confront several kinds of darkness in the aptly-titled Chasing Shadows. Along with Holly’s twin brother Corey, they are “free runners”—daredevil athletes who challenge themselves by running, climbing, and jumping cityscape obstacles. Swati Avasthi’s nimble prose captures the exuberance and rhythmic power of this sport, as Holly reflects, “Run outside and the city is no longer dead concrete and asphalt. It becomes an instrument—my instrument. Per-cuss-ive. I. Wake. It. Up.” Often, the trio practice off-hours in run-down neighborhoods. They have not thought much about other dangers lurking in Chicago until a random shooter kills Corey. Ending the first chapter, that slaughter and its aftermath are the heart of this hybrid novel.

Best friends, Chicago high school seniors Holly Trask and Savitri Mathur confront several kinds of darkness in the aptly-titled Chasing Shadows. Along with Holly’s twin brother Corey, they are “free runners”—daredevil athletes who challenge themselves by running, climbing, and jumping cityscape obstacles. Swati Avasthi’s nimble prose captures the exuberance and rhythmic power of this sport, as Holly reflects, “Run outside and the city is no longer dead concrete and asphalt. It becomes an instrument—my instrument. Per-cuss-ive. I. Wake. It. Up.” Often, the trio practice off-hours in run-down neighborhoods. They have not thought much about other dangers lurking in Chicago until a random shooter kills Corey. Ending the first chapter, that slaughter and its aftermath are the heart of this hybrid novel. Both friends grieve, but it is Holly who cannot stop reliving this event or accept a Corey-less world. She begins to fantasize ways in which Corey’s spirit might be released from a limbo-like place called “the Shadowlands.” Holly visualizes the Shadowlands and its ruler, a half-snake creature named Kortha, in distorted images from the Hindu comic books that Indian-American Savitri shared when they were in grade school together. Like DiCamillo’s Flora, Avasthi’s teens are comics fans, favoring a superhero called the Leopardess as well as the religious adventures that were a mainstay of

Both friends grieve, but it is Holly who cannot stop reliving this event or accept a Corey-less world. She begins to fantasize ways in which Corey’s spirit might be released from a limbo-like place called “the Shadowlands.” Holly visualizes the Shadowlands and its ruler, a half-snake creature named Kortha, in distorted images from the Hindu comic books that Indian-American Savitri shared when they were in grade school together. Like DiCamillo’s Flora, Avasthi’s teens are comics fans, favoring a superhero called the Leopardess as well as the religious adventures that were a mainstay of  Other ‘hybrid novels’ on my piles of recently-read/to-be-read books include Andrew Smith and Sam Bosma’s Winger and Cecil Castellucci and Nate Powell’s The Year of the Beasts. Have you read these young adult novels? Perhaps there are other hybrid works that you would like to recommend. Hunkering down with a good book or two certainly makes this arctic Minnesota winter more bearable. Brrrr …

Other ‘hybrid novels’ on my piles of recently-read/to-be-read books include Andrew Smith and Sam Bosma’s Winger and Cecil Castellucci and Nate Powell’s The Year of the Beasts. Have you read these young adult novels? Perhaps there are other hybrid works that you would like to recommend. Hunkering down with a good book or two certainly makes this arctic Minnesota winter more bearable. Brrrr …  The years seem to speed by these days, yet I remember when it felt as though I had all the time in the world. In fact, as a child the wait to become grown-up seemed impossibly long. Ironically, some of my childhood experiences remain more vivid today than some sights and sounds that are just a decade old. Neuroscientist David Eagleman,

The years seem to speed by these days, yet I remember when it felt as though I had all the time in the world. In fact, as a child the wait to become grown-up seemed impossibly long. Ironically, some of my childhood experiences remain more vivid today than some sights and sounds that are just a decade old. Neuroscientist David Eagleman,  Marble Season follows a group of children in a mainly Mexican-American neighborhood in 1960s California. The book depicts a seemingly endless succession of childhood days, with only a background high-in-the-sky sun or darkened house silhouette to mark time passing. Huey, the central character in this semi-autobiographical work, is as obsessed with comics, TV shows, and popular music as its working-class author/illustrator was in the mid-1960s, when he too was roughly 8 to 11 years old. Whenever Huey, his brothers, and neighborhood kids talk, characters such as Superman, Officer Toody from Car 54, Where Are You?, and that sensational new singing group, the ‘Beatos,’ are central topics of conversation. (For today’s readers, Hernandez includes an Afterword, identifying page-by-page all the pop culture references in the book.) Huey even scripts his own plays featuring superhero adventures, sometimes using his G.I. Joe action hero and other times costuming himself as Captain America. How other kids respond to Huey’s enthusiasm—some mockingly, others with superficial interest, only one or two with equal passion—is painfully realistic. Hyperactive Lucio is predictably unreliable. Hernandez’s dialogue captures the rhythms of childish taunts and of Huey’s hesitations such as “Well, we … I just wanted to … OK, We’re done.” Another childhood reality is the way Huey’s daily life is limited by a tagalong toddler brother and an older brother, whose ‘grounding’ also affects Huey’s access to comics.

Marble Season follows a group of children in a mainly Mexican-American neighborhood in 1960s California. The book depicts a seemingly endless succession of childhood days, with only a background high-in-the-sky sun or darkened house silhouette to mark time passing. Huey, the central character in this semi-autobiographical work, is as obsessed with comics, TV shows, and popular music as its working-class author/illustrator was in the mid-1960s, when he too was roughly 8 to 11 years old. Whenever Huey, his brothers, and neighborhood kids talk, characters such as Superman, Officer Toody from Car 54, Where Are You?, and that sensational new singing group, the ‘Beatos,’ are central topics of conversation. (For today’s readers, Hernandez includes an Afterword, identifying page-by-page all the pop culture references in the book.) Huey even scripts his own plays featuring superhero adventures, sometimes using his G.I. Joe action hero and other times costuming himself as Captain America. How other kids respond to Huey’s enthusiasm—some mockingly, others with superficial interest, only one or two with equal passion—is painfully realistic. Hyperactive Lucio is predictably unreliable. Hernandez’s dialogue captures the rhythms of childish taunts and of Huey’s hesitations such as “Well, we … I just wanted to … OK, We’re done.” Another childhood reality is the way Huey’s daily life is limited by a tagalong toddler brother and an older brother, whose ‘grounding’ also affects Huey’s access to comics. Sharp, clear lines capture the quizzical expressions, slumped shoulders, and proud posturing of these characters in their changing interactions with each other. Visuals are often key here, since many of Marble Season’s black-and-white panels are wordless, encouraging readers to draw our own conclusions about events and to experience time the way the characters do. Hernandez’s omission of word boxes, often used to indicate time, is another technique that focuses reader attention on the characters’ experience. This is true of the younger girl who, in several panels depicting painful attempts, manages to secretly swallow rather than play with Huey’s marbles. It is also true of the toddler brother who waits, eye wide-open, during a seemingly endless nap time. Childhood itself seems endless, yet Huey has mixed feelings about leaving it. On the last page of Marble Season, as he confides to a playmate, “I guess what can be scary sometimes is thinking about what I’ll be like in the future. I just hope I like being a grown up.”

Sharp, clear lines capture the quizzical expressions, slumped shoulders, and proud posturing of these characters in their changing interactions with each other. Visuals are often key here, since many of Marble Season’s black-and-white panels are wordless, encouraging readers to draw our own conclusions about events and to experience time the way the characters do. Hernandez’s omission of word boxes, often used to indicate time, is another technique that focuses reader attention on the characters’ experience. This is true of the younger girl who, in several panels depicting painful attempts, manages to secretly swallow rather than play with Huey’s marbles. It is also true of the toddler brother who waits, eye wide-open, during a seemingly endless nap time. Childhood itself seems endless, yet Huey has mixed feelings about leaving it. On the last page of Marble Season, as he confides to a playmate, “I guess what can be scary sometimes is thinking about what I’ll be like in the future. I just hope I like being a grown up.” From the first, totally black panel (which turns out to be the interior of newborn Julio’s wailing mouth) to the final totally black panel (the interior of centenarian Julio’s gaping mouth, as he lies dying), we are transfixed by Hernandez’s dramatic uses of black and white. A page of looming, ever-growing storm clouds needs no words to convey young Julio’s dismay after his first day of school. His joy in learning has been destroyed along with the book school bullies rip from his hands as they torment and humiliate him, too. Later, we see how 20th century landmark events—the Depression, droughts, wars, and social upheavals such as the civil and gay rights movements—affect Julio’s extended family. Sadly, unlike a gay great-nephew who lives openly and happily with his partner, Julio himself remains a closeted homosexual, finally denying his only lover and never admitting or acting on his strong feelings for lifelong-friend Tommy.

From the first, totally black panel (which turns out to be the interior of newborn Julio’s wailing mouth) to the final totally black panel (the interior of centenarian Julio’s gaping mouth, as he lies dying), we are transfixed by Hernandez’s dramatic uses of black and white. A page of looming, ever-growing storm clouds needs no words to convey young Julio’s dismay after his first day of school. His joy in learning has been destroyed along with the book school bullies rip from his hands as they torment and humiliate him, too. Later, we see how 20th century landmark events—the Depression, droughts, wars, and social upheavals such as the civil and gay rights movements—affect Julio’s extended family. Sadly, unlike a gay great-nephew who lives openly and happily with his partner, Julio himself remains a closeted homosexual, finally denying his only lover and never admitting or acting on his strong feelings for lifelong-friend Tommy. Other family secrets are hinted at through elliptical comments and visual cues that readers must ‘piece together’ for ourselves. One involves the child abuse perpetrated on several generations by Julio’s Uncle Juan. One of Julio’s other great-nephews finally exacts brutal justice on the elderly Juan. Another family mystery is the reason for a difficult journey young Julio’s father undertakes early in the novel. It appears that in this good Catholic family he is a practicing crypto-Jew, a descendent of Jews who escaped the Spanish Inquisition by hiding their true beliefs. Does Julio’s mother exact a terrible price for what is in her eyes heresy, or is what happens to her husband merely bad luck? Teen readers will draw their own conclusions as they read this engrossing, melodramatic but also believable family saga.

Other family secrets are hinted at through elliptical comments and visual cues that readers must ‘piece together’ for ourselves. One involves the child abuse perpetrated on several generations by Julio’s Uncle Juan. One of Julio’s other great-nephews finally exacts brutal justice on the elderly Juan. Another family mystery is the reason for a difficult journey young Julio’s father undertakes early in the novel. It appears that in this good Catholic family he is a practicing crypto-Jew, a descendent of Jews who escaped the Spanish Inquisition by hiding their true beliefs. Does Julio’s mother exact a terrible price for what is in her eyes heresy, or is what happens to her husband merely bad luck? Teen readers will draw their own conclusions as they read this engrossing, melodramatic but also believable family saga.