Being and seeing Black boys and men . . . . Transfixed this past month by the trial of Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd, taking place just eight miles from my Bloomington, Minnesota home, I wondered what I could bring today to this shamefully epic conversation. When Daunte Wright was then killed just twenty miles from here, adding his name to the annals of police violence, I was horrified and questioned myself again. Nothing original has come to my White, middle-class mind, but I can shine a spotlight on a luminous, insightful picture book created by author “Tony Medina & 13 Artists” of color.

Being and seeing Black boys and men . . . . Transfixed this past month by the trial of Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd, taking place just eight miles from my Bloomington, Minnesota home, I wondered what I could bring today to this shamefully epic conversation. When Daunte Wright was then killed just twenty miles from here, adding his name to the annals of police violence, I was horrified and questioned myself again. Nothing original has come to my White, middle-class mind, but I can shine a spotlight on a luminous, insightful picture book created by author “Tony Medina & 13 Artists” of color.

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Boy (2018) was inspired—as award-winning Medina explains in the book’s End Notes—by two classic works of poetry: Wallace Stevens’ “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Bird” and Raymond R. Patterson’s less well-known masterpiece, “Twenty-Six Ways of Looking at a Blackman.” Those poems are too elliptical and long for most young readers, but all readers (as well as anyone who might simply be listening and looking) will appreciate the words and images in this slender picture book.

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Boy (2018) was inspired—as award-winning Medina explains in the book’s End Notes—by two classic works of poetry: Wallace Stevens’ “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Bird” and Raymond R. Patterson’s less well-known masterpiece, “Twenty-Six Ways of Looking at a Blackman.” Those poems are too elliptical and long for most young readers, but all readers (as well as anyone who might simply be listening and looking) will appreciate the words and images in this slender picture book.

Medina uses a traditional Japanese verse form to capture our hearts and imaginations. The brief tanka, as he explains here, extends by two lines the more familiar shape of the three-line, syllable-distributed haiku. In a tanka, the haiku’s framework of 5-7-5 syllables is followed by two more lines, each containing 7 syllables.

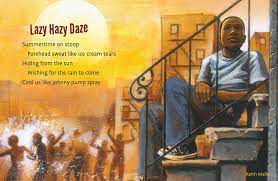

Medina has joyfully, powerfully met the challenges posed by this form’s constraints, with no awkwardness in the cascading word pictures he paints. Each of the thirteen tankas—Medina’s “thirteen ways of looking”—is illustrated by a different artist of color. The book’s back matter satisfies our curiosity about these co-creators: Floyd Cooper, Cozbi A. Cabrera, Skip Hill, Tiffany McKnight, Robert Liu-Trujillo, Keith Mallett, Shawn K. Alexander, Kesha Bruce, Brianna McCarthy, R. Gregory Christie, Ekua Holmes, Javaka Steptoe, and Chandra Cox. Their visual art, each two-page spread inspired by a separate tanka, enhances our appreciation of this book, with its multiple. distinctive artistic visions.

Medina has joyfully, powerfully met the challenges posed by this form’s constraints, with no awkwardness in the cascading word pictures he paints. Each of the thirteen tankas—Medina’s “thirteen ways of looking”—is illustrated by a different artist of color. The book’s back matter satisfies our curiosity about these co-creators: Floyd Cooper, Cozbi A. Cabrera, Skip Hill, Tiffany McKnight, Robert Liu-Trujillo, Keith Mallett, Shawn K. Alexander, Kesha Bruce, Brianna McCarthy, R. Gregory Christie, Ekua Holmes, Javaka Steptoe, and Chandra Cox. Their visual art, each two-page spread inspired by a separate tanka, enhances our appreciation of this book, with its multiple. distinctive artistic visions.

Medina’s poems speak to human truths that transcend national borders and poetic forms. Similarly, the poems’ few references to “Anacostia,” the Black Washington, D.C. neighborhood that originally inspired this volume, are verbal touchstones rather than barriers to our understanding of their insights. Notably, while Medina acknowledges the impact of poverty and prejudice on Black boys, his emphasis is on their joy in life, their loving family and community support, and their many successes, now and extending into adulthood. As Medina writes in the book’s introductory poem, “Black boys shine bright in sunlight . . . We celebrate their preciousness and creativity/ We cherish their lives.” This positive, life-affirming book is a wonderful tonic to offset the limited, destructive views of Blacks publicized so recently in murderous police violence. In visual styles ranging from realism to abstraction, sometimes employing full color but in other instances using a dramatically limited color palette, the visual artists here enhance and elaborate upon Medina’s vision.

Medina’s poems speak to human truths that transcend national borders and poetic forms. Similarly, the poems’ few references to “Anacostia,” the Black Washington, D.C. neighborhood that originally inspired this volume, are verbal touchstones rather than barriers to our understanding of their insights. Notably, while Medina acknowledges the impact of poverty and prejudice on Black boys, his emphasis is on their joy in life, their loving family and community support, and their many successes, now and extending into adulthood. As Medina writes in the book’s introductory poem, “Black boys shine bright in sunlight . . . We celebrate their preciousness and creativity/ We cherish their lives.” This positive, life-affirming book is a wonderful tonic to offset the limited, destructive views of Blacks publicized so recently in murderous police violence. In visual styles ranging from realism to abstraction, sometimes employing full color but in other instances using a dramatically limited color palette, the visual artists here enhance and elaborate upon Medina’s vision.

It is hard for me to select favorites among these soul and eye-satisfying illustrated works. Perhaps the beaming toddler, embraced by his parents in “Anacostia Angel” or the pensive young man in “Lazy Hazy Daze.” Possibly the cartoon-like energy of the tweenagers depicted in “Athlete’s Broke Bus Blues” or “Givin’ Back to the Community.” Skip Hill’s vision for “Images of Kin” is also memorable. Its boy wearing a backward-turned baseball cap transformed into a crown, his face seemingly overlaid by—in Medina’s words—a “South East Benin mask/Face like a road map of kin” is so much more than the logo drawn on his T-shirt, “Southside Kings.”

It is hard for me to select favorites among these soul and eye-satisfying illustrated works. Perhaps the beaming toddler, embraced by his parents in “Anacostia Angel” or the pensive young man in “Lazy Hazy Daze.” Possibly the cartoon-like energy of the tweenagers depicted in “Athlete’s Broke Bus Blues” or “Givin’ Back to the Community.” Skip Hill’s vision for “Images of Kin” is also memorable. Its boy wearing a backward-turned baseball cap transformed into a crown, his face seemingly overlaid by—in Medina’s words—a “South East Benin mask/Face like a road map of kin” is so much more than the logo drawn on his T-shirt, “Southside Kings.”

Yet I also cannot forget Robert Liu-Trujillos’s less upbeat spread illustrating “One Way Ticket,” whose words focus on small paychecks and mounting debts. Its subdued, limited colors show a serious-faced boy clutching a bag of groceries, with the words “One Way Ticket” drawn as a wall grafitto, an elevated train in the background. Also, “Cat at the Curb,” a tanka in which that animal has “nine lives not yet spent” [my emphasis], shows this animal darkly “Sandwiched between curb/And black radial tire.” These pages eerily bring to mind the videos of George Floyd’s car side murder. I cannot, it seems, long forget today’s raging questions about police violence.

Yet I also cannot forget Robert Liu-Trujillos’s less upbeat spread illustrating “One Way Ticket,” whose words focus on small paychecks and mounting debts. Its subdued, limited colors show a serious-faced boy clutching a bag of groceries, with the words “One Way Ticket” drawn as a wall grafitto, an elevated train in the background. Also, “Cat at the Curb,” a tanka in which that animal has “nine lives not yet spent” [my emphasis], shows this animal darkly “Sandwiched between curb/And black radial tire.” These pages eerily bring to mind the videos of George Floyd’s car side murder. I cannot, it seems, long forget today’s raging questions about police violence.

With that in mind, I will point you and tween age or teenage readers to a relevant graphic novel written earlier by Tony Medina and illustrated by Stacey Robinson and John Jennings, I am Alfonso Jones (2017). This award-winning work, centering on the fictional death of an innocent Black teen, also contains powerful examples of the real-life police murders that initiated the Black Lives Matter movement. I reviewed I am Alfonso Jones in depth here and also referenced it in this post. I myself am currently waiting for a library copy of a relevant, non-graphic compilation Tony Medina edited: Resisting Arrest: Poems to Sketch the Sky (2016). As has been said, the conviction of Derek Chauvin for George Floyd’s murder is the beginning rather than the end to gathering ideas and taking actions needed to achieve social justice.

With that in mind, I will point you and tween age or teenage readers to a relevant graphic novel written earlier by Tony Medina and illustrated by Stacey Robinson and John Jennings, I am Alfonso Jones (2017). This award-winning work, centering on the fictional death of an innocent Black teen, also contains powerful examples of the real-life police murders that initiated the Black Lives Matter movement. I reviewed I am Alfonso Jones in depth here and also referenced it in this post. I myself am currently waiting for a library copy of a relevant, non-graphic compilation Tony Medina edited: Resisting Arrest: Poems to Sketch the Sky (2016). As has been said, the conviction of Derek Chauvin for George Floyd’s murder is the beginning rather than the end to gathering ideas and taking actions needed to achieve social justice.