When is it right to break the law? To defy the police? Who decides whether an illegal act is an act of heroism rather than just a crime? These questions are on my mind today, Election Day here in the United States. This afternoon I shall stroll down the street to cast my ballot. Conveniently, our district’s polling place is on the same block as our home. Yet at other times and in other places I would have been denied the right to vote—just because I am female. Women throughout the United States were not guaranteed suffrage (the right to vote) until 1920. If I had insisted on voting in 1919, I would have been breaking the law! It took the 19th Constitutional Amendment, finally passed in 1920, to change that situation. Women in other countries struggled for and won the right to vote at other times. Some still do not have it. Suffrage also has been denied for other prejudiced reasons, such as bias against people’s race, ethnicity, or religion. Two recent graphic novels eloquently depict separate battles for equal rights under the law, placing them within the context of long-held social prejudices. Sally Heathcote, Suffragette (2014) is a brand-new British book that will suit readers already comfortable reading details of world history and tackling some adult issues. March, Book One (2013), with its inclusion of childhood events and kid “characters,” will appeal to a broader range of readers, including some upper elementary-aged students.

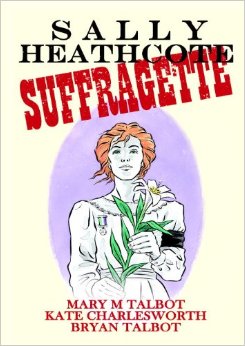

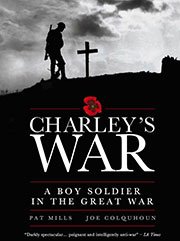

A talented trio created the fictional but history-based character of Sally Heathcote, through whose working-class eyes we see important, real-life events in British women’s struggle for the vote from the 1900s through the 1920s. This trio is Mary M. Talbot, Bryan Talbot, and Kate Charlesworth. Writer and professor Mary Talbot has collaborated once before with her acclaimed artist husband, Bryan Talbot. Their graphic novel Dotter of her Father’s Eye (2012), part biography of James Joyce’s daughter and part memoir, won the prestigious Costa Award for biography in 2012. For Sally Heathcote, Suffragette, Mary Talbot wrote the script, breaking it down into pages and panels, and Bryan Talbot did the page layouts, designed the panels, chose the colors, and drew the lettering. The busy Talbots trusted veteran illustrator Kate Charlesworth to draw the detailed images which hold our attention as we read this stirring book, filled with actions which sometimes broke the law—and laws that sometimes damaged protestors’ bodies and spirits. Charlesworth in an interview gives examples of how of how the trio worked together.

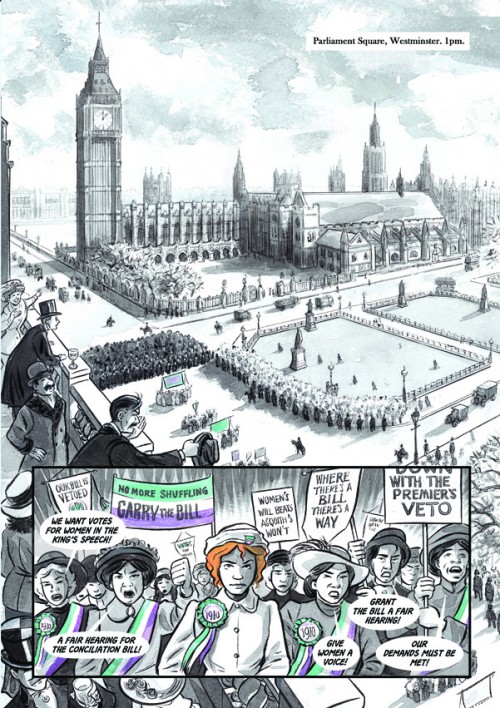

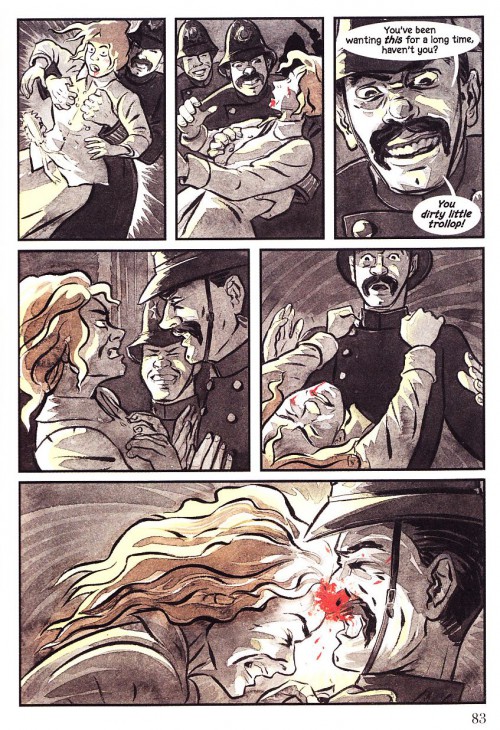

In Mary Talbot’s story, housemaid Sally Heathcote is befriended and employed by real-life luminaries in the British women’s suffrage movement: wife-and-husband Emmeline and Fred Pethick-Laurence, Emmaline Pankhurst, and her daughters Sylvia and Christabel. Sally herself becomes an activist, caught up in the violence that swirled around this movement and ultimately fractured it into two main branches—one willing to commit violent crimes to further the cause and the other not. Regardless of this division, women and men who campaigned for suffrage themselves often experienced violence at the hands of officials. One famous instance—police wading into a crowded of peaceful demonstrators and brutally beating and arresting them on “Black Friday,” November 18, 1910—is depicted here in a dramatic two-page spread. Its black-and-white panorama of violence, dotted with sprays of red blood, is balanced on one end by close-ups on the faces of nervous, determined police and of jeering opponents of suffrage and on the other by the dismayed faces of campaign staffers just learning about the violent arrests. The Talbots smartly show official sanction and public downplay of such police brutality by offsetting blocked newspaper quotations on these pages: “As a rule they [the police] kept their tempers very well, but their method of shoving back the raiders lacked nothing in vigor . . . . They [the police] were at any rate kept warm by the exercise.”

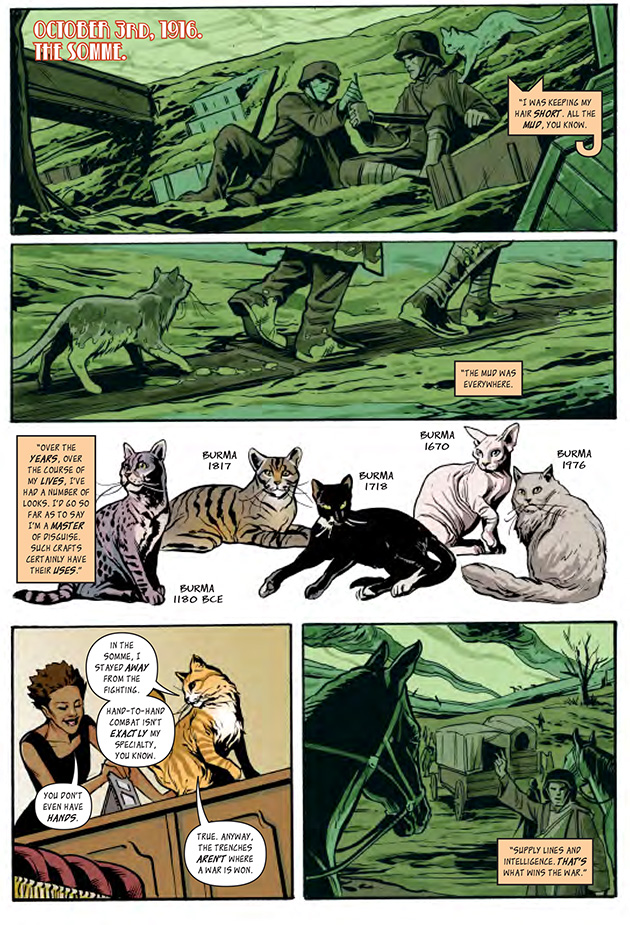

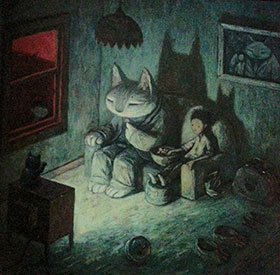

Some protestors, arrested and convicted of law breaking, suffered another form of police brutality. After these prisoners extended their protests by going on hunger strikes, officials imposed forced feeding upon them. In a series of pages, many wordless, where the repetition of eight small oblong frames per page achieves a powerful, percussive rhythm, Bryan Talbot and Kate Charlesworth show the effects of this feeding on terrorized Sally Heathcote. Close-up and mid-distance views here are especially gripping due to Talbot’s selection of images and Charlesworth’s skillful drawing of facial expression and body posture. Here, as throughout the book, the limited use of color (for instance, Sally’s red hair and blue for her moonlit prison anguish) adds effective, emotional “punch” to the storytelling. Another memorable series of images in the novel captures how official exchanges outside of prison also dehumanized women seeking suffrage. Shown in silhouette as they finally are granted an interview by the hostile British Prime Minister, the women as they make their case seem to turn into mice. At the same time, the silent, silhouetted Prime Minister and his associate are visually transforming into cats! On the next pages, when the Prime Minister verbally attacks the women’s positions, Charlesworth’s detailed drawings show these characters as full-featured, ferocious cats confronting astonished, then terrified mice.

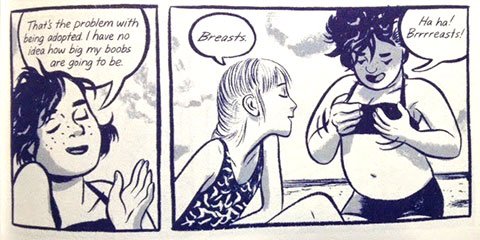

Mary Talbot’s script further engages our interest in Sally’s story by imagining how the suffrage movement affects her personal life. It costs her a close personal friend, another housemaid who fears losing her job if she associates with Sally, and it also temporarily halts a growing romantic relationship. Her sweetheart Arthur, who also works for women’s suffrage, remains with its “law-abiding” branch when Sally joins in law-breaking protests. How the two get together—and how World War I affects their lives—is movingly revealed in the novel’s framing story, set in a British nursing home in 1969. Elderly, ailing Sally–surrounded by mementos of her youth—is visited there by her daughter and granddaughter. Ironically, that 18 year old is not excited at the prospect of voting for the first time, not even sure she will “bother” with it. After this bittersweet conclusion to the novel, author Talbot includes a useful suffrage timeline, beginning in 1832 and ending in 1975. For those who wish to know more, she also includes page-by-page annotations and an extensive list of sources.

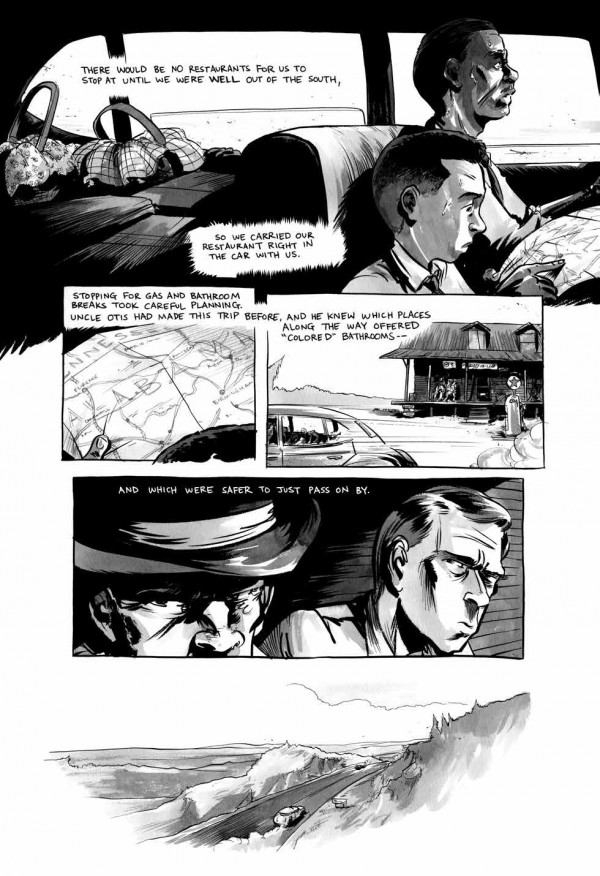

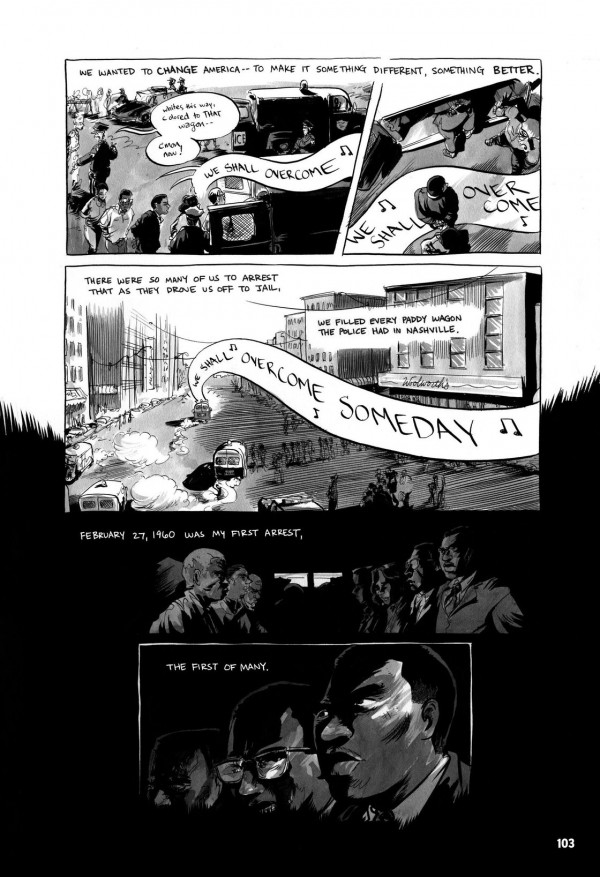

U.S. Congressman John Lewis co-authored his graphic memoir, March, Book One (2013), in large part to combat any indifference to voting—such as the complacency of Sally Heathcote’s granddaughter. Lewis, a leader of the 1960s Civil Rights movement, has said elsewhere that “In a democracy such as ours, the vote is precious, it is almost sacred. It is the most powerful nonviolent tool we have.” As a young man, this Georgia representative was arrested more than 40 times in the struggle to obtain equal rights, including equal voting rights, for African-Americans. Lewis along with others followed Dr. Martin Luther King in advocating civil disobedience, or non-violent protest. March, Book One is the first volume in a trilogy, powerfully depicting Lewis’s boyhood through his college years. It lists three creators, as Lewis worked with trusted congressional aide Andrew Aydin, who wrote the text, and this pair chose award-winning artist Nate Powell to illustrate Lewis’ story. Book One looks at the segregated South of Lewis’ youth and the early struggles to integrate public spaces, such as restaurant lunch counters, and institutions such as schools. Book Two (available in January, 2015) and Book Three deal more directly with voting rights and laws.

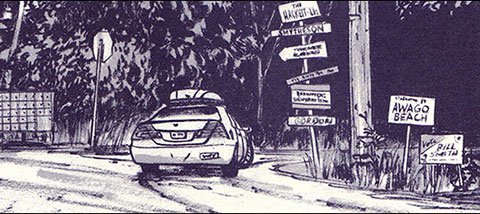

Readers of March, Book One will crave those forthcoming volumes! Lewis and Aydin zoom in on vivid, touching moments in the Congressman’s boyhood. We see him “preaching” to chickens on his family’s farm and racing off to catch a “forbidden” school bus. (His parents reluctantly declared that young John was to miss school to help with planting and harvesting. He disobeyed.) In those scenes, as throughout the entire book, Powell’s black-and-grey wash drawings superbly convey energetic motion through their variations in line and shading. Powell also effectively ‘mixes up’ the size and shape of panels, inserting or overlapping smaller ones to punctuate key dramatic points and also omitting panels at appropriately expansive or overwhelming moments. City or country vistas and the gatherings of protestors in squares or on streets are some of these defining moments in Lewis’s early years.

The perspective in these scenes is also telling. March, Book One begins with a prologue set in 1965 on the Edward Pettus Bridge, where Lewis as a young man famously marched in protest for equal voting rights. As state troopers barrel in to stop this peaceful protest, we see events finally from Lewis’s vulnerable, assaulted point of view. On the prologue’s last page, he is still standing when in an irregularly shaped panel he views a baton-wielding trooper looming over a downed, protestor, the words “THUD,” “KRAK,” and “oof” reinforcing the assault that has just occurred. Then, we only see Lewis’s hands in close-up, clawing at what must be the ground as he himself is hit. This event is confirmed by the jagged-edged blackness and inserted black panel that dominate the bottom half of the page. Illustrator Powell’s thoughtful, masterful illustrations are a fine complement to Andrew Aydin’s storytelling choices, his focus on the Pettus Bridge protest as a prologue and use of Barak Obama’s inauguration as a framing device for Lewis’s recollections. Those events are told here to two young boys visiting the Congressman’s office on that historic day. In speaking with these boys, genial and modest Lewis does not shy away from other acts of violence perpetrated in the segregated South, such as the murder of 14 year old Emmet Till. Powell’s detailed illustrations depict not only people of valiant purpose and determination but the racist hatred and suspicion of people who committed or approved of such brutal crimes. March, Book One justifiably has won numerous awards and accolades, including mention by YALSA as a Top Ten Graphic Novel for Teens.

I know I will be lining up to read March, Book Two as soon as it is available. But first I will stand in line this afternoon, exercising my precious right to vote . . . .