“Comics are the gateway drug to literacy.” This remark by Art Spiegelman, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of the graphic memoir Maus, A Survivor’s Tale (1980-1991), is not as controversial nowadays as it would have been in the 1950s. Back then, some communities banned and even burned comics, fearing they would seduce kids into criminal behavior. Today, many teachers, librarians, and parents recognize how comics and other graphic literature draw kids into reading. Some school districts, as in Maryland, have even made comics the the linchpin of their reading programs. Yet the literacy promoted by these programs too often leaves kids visually illiterate—unable to make connections or draw conclusions about the pictures and design of graphic works. This kind of half-knowledge can be as limiting and potentially dangerous as any other. So, in today’s post, I will provide some recommendations, cautions, and comments about visual literacy—and its relationships to diversity issues, past and present.

“Comics are the gateway drug to literacy.” This remark by Art Spiegelman, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of the graphic memoir Maus, A Survivor’s Tale (1980-1991), is not as controversial nowadays as it would have been in the 1950s. Back then, some communities banned and even burned comics, fearing they would seduce kids into criminal behavior. Today, many teachers, librarians, and parents recognize how comics and other graphic literature draw kids into reading. Some school districts, as in Maryland, have even made comics the the linchpin of their reading programs. Yet the literacy promoted by these programs too often leaves kids visually illiterate—unable to make connections or draw conclusions about the pictures and design of graphic works. This kind of half-knowledge can be as limiting and potentially dangerous as any other. So, in today’s post, I will provide some recommendations, cautions, and comments about visual literacy—and its relationships to diversity issues, past and present.

The punning logo of one fine specialty publisher—“Toon into Reading”—refers both to its focus on graphic works and their recent use in the reading curriculum. Established art designer and editor Francoise Mouly founded TOON Books in 2008 (together with her husband Art Spiegelman) because she wanted to offer American kids the rich comic book experiences she had growing up in France. In the 1990s, Mouly had also seen how comics held their young son’s attention, keeping him from becoming a reluctant reader. Toon Books, however, excels at even more than these admirable goals. It helps kids develop visual as well as verbal literacy.

The punning logo of one fine specialty publisher—“Toon into Reading”—refers both to its focus on graphic works and their recent use in the reading curriculum. Established art designer and editor Francoise Mouly founded TOON Books in 2008 (together with her husband Art Spiegelman) because she wanted to offer American kids the rich comic book experiences she had growing up in France. In the 1990s, Mouly had also seen how comics held their young son’s attention, keeping him from becoming a reluctant reader. Toon Books, however, excels at even more than these admirable goals. It helps kids develop visual as well as verbal literacy.

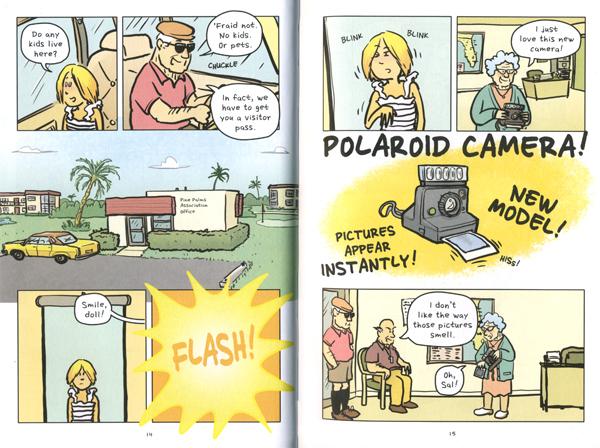

Through end notes and online guides, it offers adults ways to help young readers examine and think about the images in TOON books. This publisher’s website also engages young readers with online activities, read along videos, and texts in multiple languages. That its recommended reading lists, categorized into four distinct levels, range beyond its own publications further testifies to Toon Books’ knowledgeable sincerity. Level One is designated for brand-new readers, Level Two for emergent readers, and Level Three for “advanced readers” ready to tackle chapter books. Its newest category, labelled Toon Graphics, is aimed at ages 8 to adult, reading above 3rd grade level. Although many teachers and librarians may appreciate these distinctions, I myself dislike such prescriptive labels, particularly if they are used in rigid or restricting ways. I would rather make a dictionary available as youngsters select their reading on the basis of content or cover appeal. Being stymied by a word or unable to puzzle it out by context then becomes a mystery to solve—another achievement!

languages. That its recommended reading lists, categorized into four distinct levels, range beyond its own publications further testifies to Toon Books’ knowledgeable sincerity. Level One is designated for brand-new readers, Level Two for emergent readers, and Level Three for “advanced readers” ready to tackle chapter books. Its newest category, labelled Toon Graphics, is aimed at ages 8 to adult, reading above 3rd grade level. Although many teachers and librarians may appreciate these distinctions, I myself dislike such prescriptive labels, particularly if they are used in rigid or restricting ways. I would rather make a dictionary available as youngsters select their reading on the basis of content or cover appeal. Being stymied by a word or unable to puzzle it out by context then becomes a mystery to solve—another achievement!

I recommend you peruse Toon Books’ entire catalog, but I also want to spotlight two of its recent publications. Written and Drawn by Henrietta (2015) by Argentinian author/illustrator Liniers is a Level Three novel available in both English and Spanish editions. Its colorful, charming rendering of a young girl’s first venture into cartooning is also insightful. We see the fears, fascination, and whole-hearted fun typical of her age, identified as K-3 in the catalogue and further targeted by an accompanying Teacher’s Guide for Grades 2 and 3. I love how Liniers in a two-page spread introduces an amazing variety of words and images for “hat”! This plot-related spread is also a great, seemingly effortless teaching moment. At the Toon website, readers can also watch short videos of Liniers (pen name of Ricardo Liniers Siri) interacting with fans while wearing one of his special hats.

I recommend you peruse Toon Books’ entire catalog, but I also want to spotlight two of its recent publications. Written and Drawn by Henrietta (2015) by Argentinian author/illustrator Liniers is a Level Three novel available in both English and Spanish editions. Its colorful, charming rendering of a young girl’s first venture into cartooning is also insightful. We see the fears, fascination, and whole-hearted fun typical of her age, identified as K-3 in the catalogue and further targeted by an accompanying Teacher’s Guide for Grades 2 and 3. I love how Liniers in a two-page spread introduces an amazing variety of words and images for “hat”! This plot-related spread is also a great, seemingly effortless teaching moment. At the Toon website, readers can also watch short videos of Liniers (pen name of Ricardo Liniers Siri) interacting with fans while wearing one of his special hats.

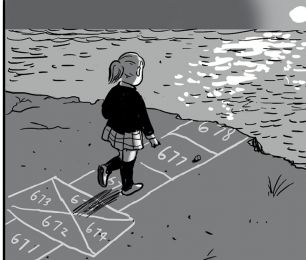

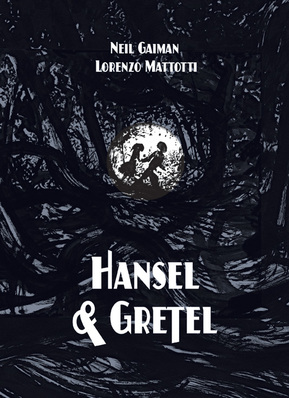

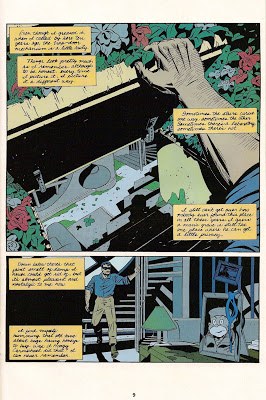

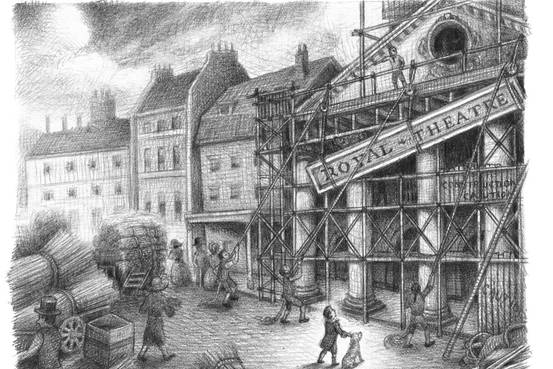

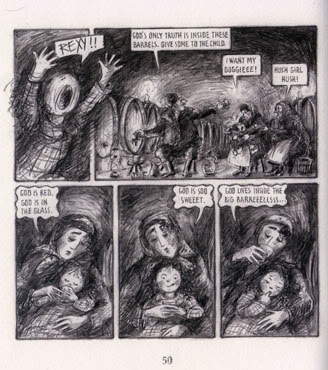

I was “wowed” by Hansel & Gretel (2014), authored by award-winning Neil Gaiman and illustrated by Lorenzo Mattotti. Published as a Toon Graphics (ages 8 to adult), this work is accompanied by a teacher’s guide demonstrating how this fairy tale may provoke discussion among tweens and teens as well as adults. Noteworthy here is how much deserved attention the guide’s authors pay to the arresting black and white images as well as Gaiman’s resonant language and narrative. Four and a half pages are devoted to “Visual Expression,” along with the six and a half pages given to the tale’s written words. Perspective, angles, and multiple interpretations of silhouetted figures are among the visual elements aptly noted here. I myself observed how Mattotti used silhouettes so well to portray ominous, predatory intent, with the witchlike character looming spiderlike at one point, while long or swirling white lines effectively convey flight or other kinds of motion. At the Toon website, readers can also watch short videos of Gaiman dramatically reading aloud parts of the tale and discussing “comics and scaring children.”

I was “wowed” by Hansel & Gretel (2014), authored by award-winning Neil Gaiman and illustrated by Lorenzo Mattotti. Published as a Toon Graphics (ages 8 to adult), this work is accompanied by a teacher’s guide demonstrating how this fairy tale may provoke discussion among tweens and teens as well as adults. Noteworthy here is how much deserved attention the guide’s authors pay to the arresting black and white images as well as Gaiman’s resonant language and narrative. Four and a half pages are devoted to “Visual Expression,” along with the six and a half pages given to the tale’s written words. Perspective, angles, and multiple interpretations of silhouetted figures are among the visual elements aptly noted here. I myself observed how Mattotti used silhouettes so well to portray ominous, predatory intent, with the witchlike character looming spiderlike at one point, while long or swirling white lines effectively convey flight or other kinds of motion. At the Toon website, readers can also watch short videos of Gaiman dramatically reading aloud parts of the tale and discussing “comics and scaring children.”

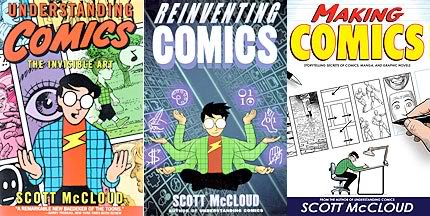

Of course, there are other tools out there to enable tweens on up to become visually literate or develop further visual sophistication. Now classic works on this topic include Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (1993), Reinventing Comics (2000), and Making Comics (2006). (I briefly discussed the impact of these works here in March, 2015, along with McCloud’s own great graphic novel, The Sculptor [2015]). Older teens and adults who enjoy theories and the history of ideas might also appreciate the multiple-award winning Unflattening (2015) by Nick Sousanis, excerpted and linked to reviews at his website.

One kind of tool I would caution about is aimed at readers who use tablets or mobile devices to view the growing number of comics and graphic novels available on line. Some downloadable apps such as Amazon’s Comixology offer digital readers a “guided view” through the text—a so-called “cinematic experience” which removes the need for personally making connections between images, connecting images and words, or rereading a work. Instead, one can follow along the path the company’s “skilled comics fan” has set for readers willing to follow it. Little or no personal visual literacy or ongoing engagement is expected from individual readers. That is quite a different outlook than Francois Mouly’s goals for Toon Books. In an interview, she has said, “With all our books, we do lesson plans of the ways to not just read the book, but reread the book. . . . [Our] ambition is . . . to make something that can be reread.”

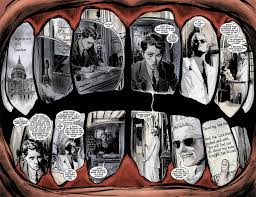

The benefits of such visual—as well as cultural and, of course, written—literacy are numerous. I was reminded of this recently when I caught up with the anniversary compilation of Will Eisner’s The Spirit: A Celebration of 75 Years (2015). Influential author/illustrator Eisner—for whom the prestigious Eisner Awards are named—was active in comics as creator and teacher from the 1930s until his death at age 87 in 2005. Although I had heard about Eisner’s long-running comics series, first published between 1940 and 1952, with its masked crime-fighter the “Spirit,” I had not read it. I did know and admire his great graphic novels, including The Contract with God Trilogy (1978 -95; 2006) and Fagin the Jew (2003; 2013, reviewed here in December, 2014). In Eisner’s version of that famous character from Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist, Eisner protested Dickens’ and early illustrators’ stereotyped depiction of Jews. At the same time, Eisner, himself Jewish, confessed that he too had been guilty of comparable prejudice, as in The Spirit his “stories . . . designed as entertainment . . . [were] nonetheless feeding a racial prejudice with this stereotype image.”

The benefits of such visual—as well as cultural and, of course, written—literacy are numerous. I was reminded of this recently when I caught up with the anniversary compilation of Will Eisner’s The Spirit: A Celebration of 75 Years (2015). Influential author/illustrator Eisner—for whom the prestigious Eisner Awards are named—was active in comics as creator and teacher from the 1930s until his death at age 87 in 2005. Although I had heard about Eisner’s long-running comics series, first published between 1940 and 1952, with its masked crime-fighter the “Spirit,” I had not read it. I did know and admire his great graphic novels, including The Contract with God Trilogy (1978 -95; 2006) and Fagin the Jew (2003; 2013, reviewed here in December, 2014). In Eisner’s version of that famous character from Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist, Eisner protested Dickens’ and early illustrators’ stereotyped depiction of Jews. At the same time, Eisner, himself Jewish, confessed that he too had been guilty of comparable prejudice, as in The Spirit his “stories . . . designed as entertainment . . . [were] nonetheless feeding a racial prejudice with this stereotype image.”

That prejudiced stereotype was about Blacks. It is the recurring character of “Ebony White”—the Black boy or teen who assists the Spirit—whose caricatured appearance and language is so breathtakingly offensive in this series. Is the fact that Ebony’s deeds are always brave and honest a strong enough counterweight to reclaim the humanity visually denied to this character? In 2008, director Frank Miller skirted this question by omitting Ebony White from the live action movie he made based on Eisner’s series. (This PG-13 film was, regardless, not well-received.) The compilation volume I read is introduced by writing luminary Neil Gaiman, who rightly praises the series’ many visual and storytelling innovations in the crime fighting genre. Yet Gaiman never mentions the character of Ebony White!

That prejudiced stereotype was about Blacks. It is the recurring character of “Ebony White”—the Black boy or teen who assists the Spirit—whose caricatured appearance and language is so breathtakingly offensive in this series. Is the fact that Ebony’s deeds are always brave and honest a strong enough counterweight to reclaim the humanity visually denied to this character? In 2008, director Frank Miller skirted this question by omitting Ebony White from the live action movie he made based on Eisner’s series. (This PG-13 film was, regardless, not well-received.) The compilation volume I read is introduced by writing luminary Neil Gaiman, who rightly praises the series’ many visual and storytelling innovations in the crime fighting genre. Yet Gaiman never mentions the character of Ebony White!

How is one to address this question? Is it enough to say, as Eisner did late in his life, that back then he did not know any better? And that all cartoons in some sense depend on stereotypes for their images? Even Francois Mouly echoes these truisms. In an interview she is quoted as having said that when and how an image is looked at determines half its meaning. She also remarked that “Cartoonists have to use clichés.” Is omitting or ignoring Ebony White the way, then, to deal with this question today? What about the pain of Black readers who unknowingly come across this visually grotesque character as they discover or delve deeper into Eisner’s works? Some of these issues are addressed by writer and critic Carol Borden in a 2010 online essay, “The Biography of Ebony White.” Journalist and comics historian Jet Heer also writes about ways Ebony White both fit and did not fit racial stereotypes typical in 1930s through 1950s cartoons..

These questions are, unfortunately, not ones that can be relegated only to examination of the past. The cultural and visual literacy with which we create and approach books remains controversial, as recent responses to the children’s picture book A Birthday Cake for George Washington (2015) show. Its publisher Scholastic withdrew this book from distribution after much social media criticism of its depiction of slavery, centering on Hercules, the slave chef owned by our first president.

These questions are, unfortunately, not ones that can be relegated only to examination of the past. The cultural and visual literacy with which we create and approach books remains controversial, as recent responses to the children’s picture book A Birthday Cake for George Washington (2015) show. Its publisher Scholastic withdrew this book from distribution after much social media criticism of its depiction of slavery, centering on Hercules, the slave chef owned by our first president.

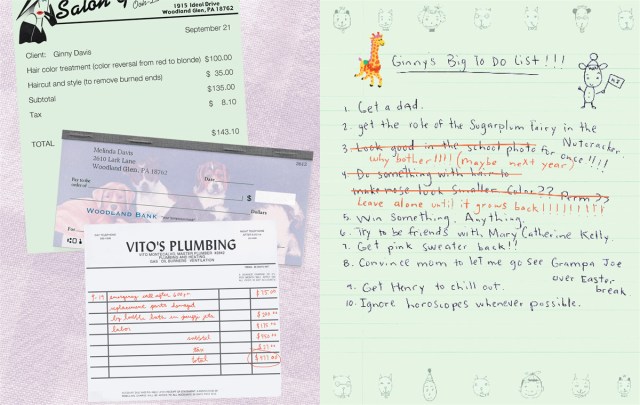

Although Hercules was perhaps the U.S.’s first celebrity chef, after the fictionalized events in this book he later fled to freedom—a fact relegated by the publisher to end notes. This was one criticism of the book. Another was of the uniformly smiling slave faces throughout the book. Even its author Ramin Ganeshram was not happy with the illustrations by Vanessa Brantley-Newton. (She also wanted a different conclusion for the published text.) While Ganeshram mentions that the “overjoviality” of these images also disturbed her, there is a further way those gleaming white smiles in evenly dark faces distressed me. They were too like the stereotyped minstrel show “blacked up” faces once used to gleefully mock Blacks. Is it possible that somewhere in the chain of command at Scholastic there was an initial failure of visual and cultural literacy that overrode Ganeshram’s objections?

A probable portrait of Hercules by renowned American painter Gilbert Stuart depicts a clear-eyed, serious man—neither smiling nor frowning. Perhaps that image might have been included and otherwise used as inspiration in A Birthday Cake for George Washington. (Perhaps libraries which hold copies of this book might insert or display this image, appropriately captioned, in or near it.) Even so, I know that I remain uncomfortable with Scholastic’s having ceased publication and distribution of this problematic book. Their decision smacks too much of the burning and banning of books once common in Nazi Germany as well as the 1950s comics-fearing U.S.A. And I am in agreement with the maxim that “Those who do not remember the past are doomed to repeat it.” Visual literacy is one vital component to such collective memory.

A probable portrait of Hercules by renowned American painter Gilbert Stuart depicts a clear-eyed, serious man—neither smiling nor frowning. Perhaps that image might have been included and otherwise used as inspiration in A Birthday Cake for George Washington. (Perhaps libraries which hold copies of this book might insert or display this image, appropriately captioned, in or near it.) Even so, I know that I remain uncomfortable with Scholastic’s having ceased publication and distribution of this problematic book. Their decision smacks too much of the burning and banning of books once common in Nazi Germany as well as the 1950s comics-fearing U.S.A. And I am in agreement with the maxim that “Those who do not remember the past are doomed to repeat it.” Visual literacy is one vital component to such collective memory.

And it is visual literacy which provides one creative response to the issues raised by Eisner’s racist images of Ebony White. The anniversary compilation of Spirit stories concludes with two later homages to the series. In one of these—“ Last Night I Dreamed of Dr. Cobra,” written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Daniel Torres—Ebony Black only appears as an image, in a photograph framed and displayed on a tabletop. He is remembered, his existence and worth validated, whatever discomfort this stereotypical character might have caused during the 1940s and 50s and certainly causes now. Visually astute readers will catch this reference. “Last Night I Dreamed of Dr. Cobra” was first published in 1998. It was later collected in a volume of nineteen homage stories by multiple authors and illustrators, Will Eisner’s The Spirit: The New Adventures (2009;2016). I am curious to see if and how Ebony White appears in other stories there, just as I am interested in reading other current and forthcoming volumes published by savvy Toon Books. Such treasures provided by my library card!

And it is visual literacy which provides one creative response to the issues raised by Eisner’s racist images of Ebony White. The anniversary compilation of Spirit stories concludes with two later homages to the series. In one of these—“ Last Night I Dreamed of Dr. Cobra,” written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Daniel Torres—Ebony Black only appears as an image, in a photograph framed and displayed on a tabletop. He is remembered, his existence and worth validated, whatever discomfort this stereotypical character might have caused during the 1940s and 50s and certainly causes now. Visually astute readers will catch this reference. “Last Night I Dreamed of Dr. Cobra” was first published in 1998. It was later collected in a volume of nineteen homage stories by multiple authors and illustrators, Will Eisner’s The Spirit: The New Adventures (2009;2016). I am curious to see if and how Ebony White appears in other stories there, just as I am interested in reading other current and forthcoming volumes published by savvy Toon Books. Such treasures provided by my library card!

What connects award-winning graphic author/illustrator Gene Luen Yang and film luminary Orson Welles? Both have cracked codes—figuratively, and in Yang’s case literally, too—and made history. Welles did this back in the 1930s and 40s, when kids sometimes thought that access to power was as simple as owning the right “secret decoder” pin or ring. Anyone—regardless of race, religion, or background—could supposedly become a member of exclusive clubs linked to

What connects award-winning graphic author/illustrator Gene Luen Yang and film luminary Orson Welles? Both have cracked codes—figuratively, and in Yang’s case literally, too—and made history. Welles did this back in the 1930s and 40s, when kids sometimes thought that access to power was as simple as owning the right “secret decoder” pin or ring. Anyone—regardless of race, religion, or background—could supposedly become a member of exclusive clubs linked to  One of two central characters in this jewel heist mystery by author/illustrator Jonathan Cash is a Black actress cast in Welles’ play. Teresa Harris’ “day job” is being a maid at the hotel, where she becomes both suspect and detective in the theft. How her race also figures in this part of Teresa’s life is another reason I want to highlight Cash’s book today, the start of Black History Month. Readers tween and up will find the novel eye-opening as well as entertaining.

One of two central characters in this jewel heist mystery by author/illustrator Jonathan Cash is a Black actress cast in Welles’ play. Teresa Harris’ “day job” is being a maid at the hotel, where she becomes both suspect and detective in the theft. How her race also figures in this part of Teresa’s life is another reason I want to highlight Cash’s book today, the start of Black History Month. Readers tween and up will find the novel eye-opening as well as entertaining.

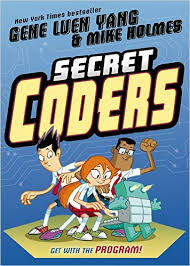

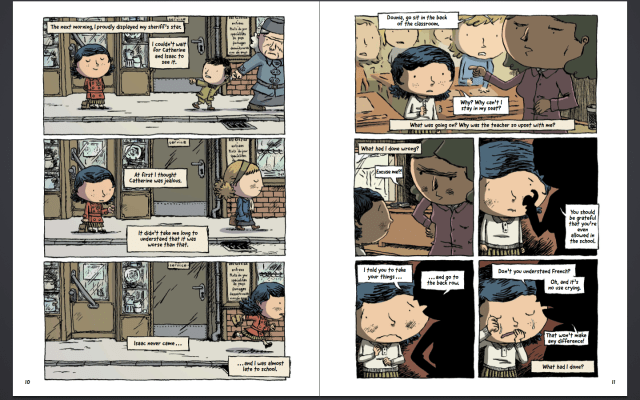

Gene Luen Yang’s latest stand-alone graphic novel, with its 7th grade protagonists, will appeal to upper elementary as well as tween readers. Illustrated by Mike Holmes, Secret Coders (2015) is also a mystery novel. It combines recognizable school routines such as lunch hour, gym class, and homework with mysterious, odd occurrences—puzzles solvable by understanding and using the binary code central to computer programming! New student Hopper thinks Stately Academy looks “like a haunted house,” but she has no idea about what really makes it strange. Struggling to fit in, Hopper asks questions that win her one new friend, but also send her to the principal’s office and even into danger.

Gene Luen Yang’s latest stand-alone graphic novel, with its 7th grade protagonists, will appeal to upper elementary as well as tween readers. Illustrated by Mike Holmes, Secret Coders (2015) is also a mystery novel. It combines recognizable school routines such as lunch hour, gym class, and homework with mysterious, odd occurrences—puzzles solvable by understanding and using the binary code central to computer programming! New student Hopper thinks Stately Academy looks “like a haunted house,” but she has no idea about what really makes it strange. Struggling to fit in, Hopper asks questions that win her one new friend, but also send her to the principal’s office and even into danger.

In his multiple-award-winning graphic novel American Born Chinese (2006), Yang uses Chinese mythology to enrich his painfully humorous look at the identity problems of a child of first generation immigrants. In his duology Boxers and Saints (2013, reviewed here in August, 2013), Yang dramatically conveys the brutal clash of cultures and religions in China during the Boxer Rebellion of 1899-1901. In The Shadow Hero (2014, reviewed here in March 2014), along with illustrator Sonny Lieuw Yang entertainingly uses comic book history, Chinese lore, and immigrant experience to develop a Chinese-American superhero. Their Shadow Hero is set during the era when Welles was producing that groundbreaking Macbeth!

In his multiple-award-winning graphic novel American Born Chinese (2006), Yang uses Chinese mythology to enrich his painfully humorous look at the identity problems of a child of first generation immigrants. In his duology Boxers and Saints (2013, reviewed here in August, 2013), Yang dramatically conveys the brutal clash of cultures and religions in China during the Boxer Rebellion of 1899-1901. In The Shadow Hero (2014, reviewed here in March 2014), along with illustrator Sonny Lieuw Yang entertainingly uses comic book history, Chinese lore, and immigrant experience to develop a Chinese-American superhero. Their Shadow Hero is set during the era when Welles was producing that groundbreaking Macbeth!  graphic novelist to earn this distinction. Yang has said that he will use his new, prominent position to advocate for

graphic novelist to earn this distinction. Yang has said that he will use his new, prominent position to advocate for

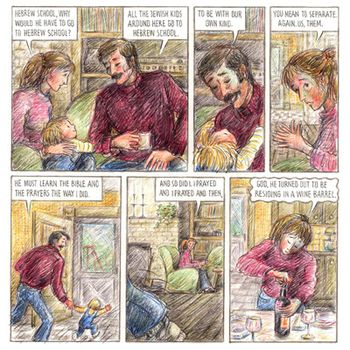

The month of December has long foregrounded issues of diversity in multicultural countries. As Christmas approaches in predominantly Christian countries, how do we acknowledge the presence and holidays of other religious groups? Some non-Christian parents even call the problems raised in our families by widespread Christmas decorations and gift-giving the “December Dilemma.” Finding solutions to this dilemma is akin to another responsibility all adults bear. How do we explain to young people that history is woven of many strands, its warp and woof sometimes obscuring the experiences of different groups?

The month of December has long foregrounded issues of diversity in multicultural countries. As Christmas approaches in predominantly Christian countries, how do we acknowledge the presence and holidays of other religious groups? Some non-Christian parents even call the problems raised in our families by widespread Christmas decorations and gift-giving the “December Dilemma.” Finding solutions to this dilemma is akin to another responsibility all adults bear. How do we explain to young people that history is woven of many strands, its warp and woof sometimes obscuring the experiences of different groups? This past month—with its shocking Islamic terrorist attacks in Paris and elsewhere—had me shakily looking backward as well as ahead. I despaired that my February, 2015 blog post, written in response to terrorist attacks in Paris last January, could have been reposted here today. Only the introductory remarks in “Jews, Muslims, Christians: The Rabbi’s Cat Speaks” would have needed updating. On a similar, but thankfully non-violent note, recent controversy raised by a new non-fiction picture book highlights another aspect of the questions about history and culture so prominent in December.

This past month—with its shocking Islamic terrorist attacks in Paris and elsewhere—had me shakily looking backward as well as ahead. I despaired that my February, 2015 blog post, written in response to terrorist attacks in Paris last January, could have been reposted here today. Only the introductory remarks in “Jews, Muslims, Christians: The Rabbi’s Cat Speaks” would have needed updating. On a similar, but thankfully non-violent note, recent controversy raised by a new non-fiction picture book highlights another aspect of the questions about history and culture so prominent in December.  Writers and readers of color, in particular, have taken issue with the way in which slavery is depicted in A Fine Dessert: Four Centuries, Four Families, One Delicious Treat (2015), written by Emily Jenkins and Illustrated by Sophie Blackhall. This history of the dessert known as “blackberry fool” even contains a recipe for it. Opponents of this work’s depiction of life in 1810 South Carolina (one quarter of the book) say its creators obscure slavery’s real horrors, with Black characters—a slave mother, her young daughter, and a young boy—who are too calm and sometimes smile. Their critiques remind me, in these years of terrorist attacks, of the different ways twentieth century history in the Middle East is framed. For many people, 1948 marks the celebratory establishment of the state of Israel; yet displaced Palestinians, among other people, refer to that year and Israel’s recognition by the United

Writers and readers of color, in particular, have taken issue with the way in which slavery is depicted in A Fine Dessert: Four Centuries, Four Families, One Delicious Treat (2015), written by Emily Jenkins and Illustrated by Sophie Blackhall. This history of the dessert known as “blackberry fool” even contains a recipe for it. Opponents of this work’s depiction of life in 1810 South Carolina (one quarter of the book) say its creators obscure slavery’s real horrors, with Black characters—a slave mother, her young daughter, and a young boy—who are too calm and sometimes smile. Their critiques remind me, in these years of terrorist attacks, of the different ways twentieth century history in the Middle East is framed. For many people, 1948 marks the celebratory establishment of the state of Israel; yet displaced Palestinians, among other people, refer to that year and Israel’s recognition by the United  Nations as “the Catastrophe.” These conflicting views are vividly portrayed by graphic journalist Joe Sacco in such works for adults and older readers as Palestine (1996) and Footnotes in Gaza (2009). There are no easy answers to the real-life problems stemming from these historical events, among others, however they are labelled.

Nations as “the Catastrophe.” These conflicting views are vividly portrayed by graphic journalist Joe Sacco in such works for adults and older readers as Palestine (1996) and Footnotes in Gaza (2009). There are no easy answers to the real-life problems stemming from these historical events, among others, however they are labelled.

Mirka. Its wryly humorous subtitle—“Yet Another 11 Year Old Time Travelling Orthodox Jewish Babysitter”—will come as no surprise to fans of Hereville: How Mirka Got Her Sword (2010) and Hereville: How Mirka Met a Meteorite (2012) , both reviewed here in April, 2013. Deutsch uses humor and smart insights about family relationships to depict both daily life inside a closed, ultra-Orthodox community and rebellious Mirka’s fantastic encounters with supernatural creatures and events. Even as curious Mirka sometimes disobeys parents and community rules, her love for family and tradition remains strong. In fact, as in the first volumes, family bonds and tradition help Mirka overcome the fantastic dangers she encounters. Here she thwarts a treacherous enchanted fish!

Mirka. Its wryly humorous subtitle—“Yet Another 11 Year Old Time Travelling Orthodox Jewish Babysitter”—will come as no surprise to fans of Hereville: How Mirka Got Her Sword (2010) and Hereville: How Mirka Met a Meteorite (2012) , both reviewed here in April, 2013. Deutsch uses humor and smart insights about family relationships to depict both daily life inside a closed, ultra-Orthodox community and rebellious Mirka’s fantastic encounters with supernatural creatures and events. Even as curious Mirka sometimes disobeys parents and community rules, her love for family and tradition remains strong. In fact, as in the first volumes, family bonds and tradition help Mirka overcome the fantastic dangers she encounters. Here she thwarts a treacherous enchanted fish!  Both colorful works have text in three languages: English, Yiddish, and Spanish—a mélange authentically reflecting the multicultural experiences of their contemporary New York City setting. The warmth and fellow-feeling that cross species lines—here between kitten and birds and earlier, between chicken Yetta and the South American parrots who help her survive—are heartwarming. Simple, colloquial language blends well with vivid colors, preventing the story from becoming too sweet by the book’s end, when every creature and person has the chance to enjoy a savory, traditional Hanukkah food. An additional treat for readers may be found online

Both colorful works have text in three languages: English, Yiddish, and Spanish—a mélange authentically reflecting the multicultural experiences of their contemporary New York City setting. The warmth and fellow-feeling that cross species lines—here between kitten and birds and earlier, between chicken Yetta and the South American parrots who help her survive—are heartwarming. Simple, colloquial language blends well with vivid colors, preventing the story from becoming too sweet by the book’s end, when every creature and person has the chance to enjoy a savory, traditional Hanukkah food. An additional treat for readers may be found online  Written by Sean Michael Wilson and illustrated by Akiko Shimojima, with poetry translations by J.P. Seaton, this graphic work has two main parts. First, Wilson compiles and retells stories about the two Chinese men, friends now regarded as Buddhist bodhisattvas or saints, who may have lived between 600 and 900 C.E. Their legendary humor and eccentric behavior questioned their society’s traditional rules and values. The next half consists of poems they wrote, embodying Zen Buddhist views of the natural world and human existence. Shimojima’s black and white illustrations are really inspired here. Her selection of such natural objects as fruit trees or an aging human body give clear meaning to poetic abstractions, while her shifts in perspective and distance, with close-ups being particularly telling, enhance each poem’s progression of ideas and major points.

Written by Sean Michael Wilson and illustrated by Akiko Shimojima, with poetry translations by J.P. Seaton, this graphic work has two main parts. First, Wilson compiles and retells stories about the two Chinese men, friends now regarded as Buddhist bodhisattvas or saints, who may have lived between 600 and 900 C.E. Their legendary humor and eccentric behavior questioned their society’s traditional rules and values. The next half consists of poems they wrote, embodying Zen Buddhist views of the natural world and human existence. Shimojima’s black and white illustrations are really inspired here. Her selection of such natural objects as fruit trees or an aging human body give clear meaning to poetic abstractions, while her shifts in perspective and distance, with close-ups being particularly telling, enhance each poem’s progression of ideas and major points.

n as a board game to depict the constant upheavals begun with this first move. She and her family are merely playing pieces, shifted along the path’s squares by wartime chance, represented by the game’s dice. Ironically, when this civil war finally ends, Zeina and her family are able to return to their “home neighborhood,” now safe in a way she has never known. The feared “enemy territory,” once hosting deadly snipers and bombers, had begun just across the street! Yet the grown-up Zeina still cannot take safety for granted—in some senses she remains a refugee. The final pages include one set in Paris in 2008, as Zeina fearfully “remembers the bombing” when a thunderstorm awakens her. Refugee wounds are not merely physical.

n as a board game to depict the constant upheavals begun with this first move. She and her family are merely playing pieces, shifted along the path’s squares by wartime chance, represented by the game’s dice. Ironically, when this civil war finally ends, Zeina and her family are able to return to their “home neighborhood,” now safe in a way she has never known. The feared “enemy territory,” once hosting deadly snipers and bombers, had begun just across the street! Yet the grown-up Zeina still cannot take safety for granted—in some senses she remains a refugee. The final pages include one set in Paris in 2008, as Zeina fearfully “remembers the bombing” when a thunderstorm awakens her. Refugee wounds are not merely physical.